Picasso On Intuition

“To know what you’re going to draw, you have to begin drawing.”

“Inspiration is for amateurs — the rest of us just show up and get to work,” painter Chuck Close memorably scoffed. “Show up, show up, show up,” novelist Isabelle Allende echoed in heradvice to aspiring writers, “and after a while the muse shows up, too.” Legendary composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky put it similarly in an1878 letter to his benefactress: “A self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood.” Indeed, this notion that creativity and fruitful ideas come not from the passive resignation to a muse but from the active application of work ethic — ordiscipline, something the late and great Massimo Vignelli advocated for as the engine of creative work — is something legions of creative luminaries have articulated over the ages, alongside the parallel inquiry of where ideas come from. But, perhaps unsurprisingly, the most succinct and elegant articulation comes from one of the greatest artists of all time.

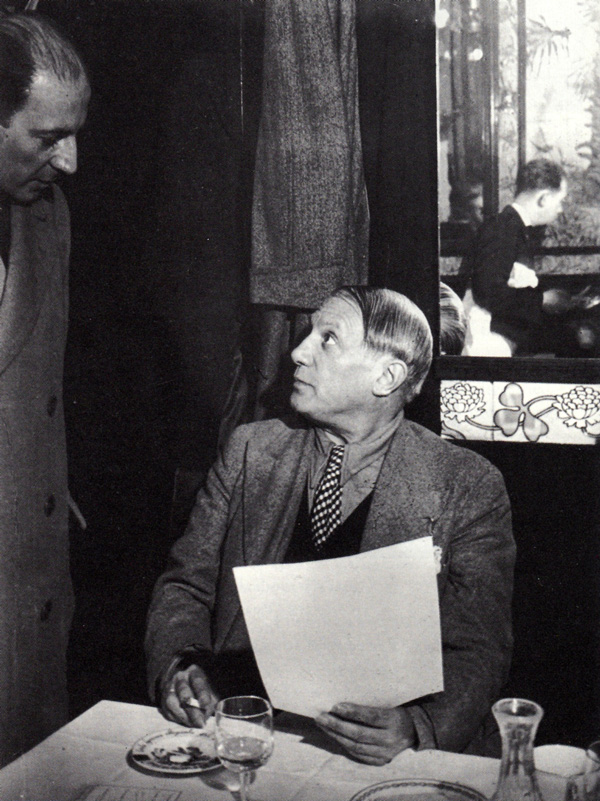

Picasso having lunch at the Brasserie Lipp, chatting with Pierre Matisse, Henri Matisse's son. Photograph by Brassaï.

This was one of the questions the famed Hungarian photographer Brassaï posed to Pablo Picasso over the course of their 30-year-long interview series, collected in Conversations with Picasso (public library) — the same superb 1964 volume that gave us Picasso on success and why you should never compromise creatively. When Brassaï asks whether the painter’s ideas come to him “by chance or by design,” Picasso slips in some sidewise wisdom on the tyranny of “creative block” and responds:

I don’t have a clue. Ideas are simply starting points. I can rarely set them down as they come to my mind. As soon as I start to work, others well up in my pen. To know what you’re going to draw, you have to begin drawing… When I find myself facing a blank page, that’s always going through my head. What I capture in spite of myself interests me more than my own ideas.

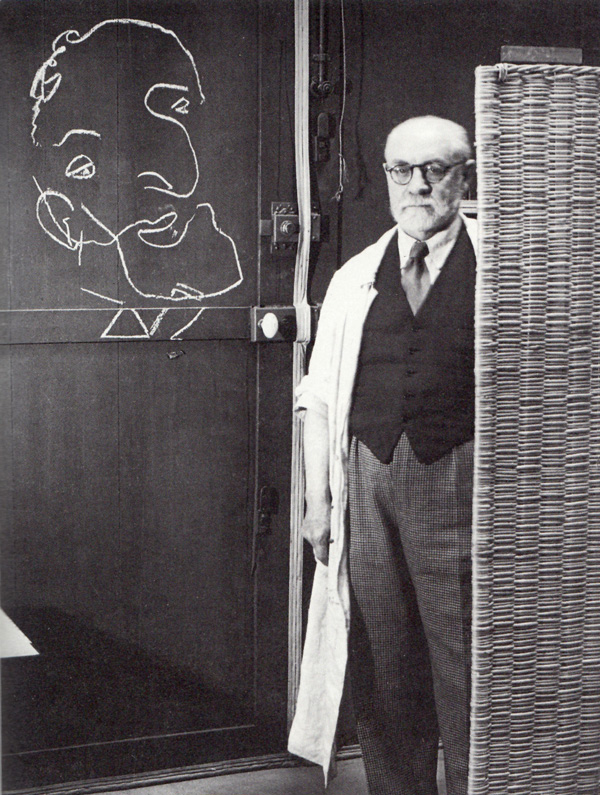

The chalk portrait of Picasso that Henri Matisse drew blindfolded. Photograph by Brassaï.

To further illustrate this notion that the best creative work happens when the rational, self-editing mind gets out of the way of the intuitive inclination — something Ray Bradbury articulated beautifully in a 1974 interview — Picasso offers an illustrative example. Despite being both a professional admirer and a personal friend of Matisse’s, he cites the painter’s notoriously methodical creative process as a betrayal of this notion that an artist should honor his or her initial creative intuition:

Matisse does a drawing, then he recopies it. He recopies it five times, ten times, each time with cleaner lines. He is persuaded that the last one, the most spare, is the best, the purest, the definitive one; and yet, usually it’s the first. When it comes to drawing, nothing is better than the first sketch.

Conversations with Picasso is an enormously rewarding read in its entirety. Complement this particular extract with a five-step “technique for producing ideas” from 1939, then revisit David Lynch on where ideas come from and some thoughts on the subject from Neil Gaiman.

Maria Popova is a cultural curator and curious mind at large, who also writes for Wired UK, The Atlantic and Design Observer, and is the founder and editor in chief of Brain Pickings (which offers a free weekly newsletter).