How the stunning abstract art of Hilma af Klint opens our eyes to new ways of seeing

Review: Hilma af Klint, The Secret Paintings. Art Gallery of New South Wales.

In 1986, those art historians who see art as some form of linear progression “improving” with time received a rude shock. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s exhibition The Spiritual in Art — Abstract Paintings 1890 – 1985 introduced a hitherto unknown woman artist.

The issue was not just that this art was so exquisitely beautiful — but that the paintings had been painted in the early 20th century.

Hilma af Klint was once known as a minor academic Swedish artist. Born in 1862, she had been one of the first women to graduate from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm and had exhibited at the Swedish General Art Association.

But these paintings on display in Los Angeles revealed another life, a different art. Her involvement with spiritualism had radicalised her art to such an extent she can only be described as one of the great abstract artists.

Her work was the sensation of the 2013 Venice Biennale, with a full scale retrospective organised by the Moderna Museet shown in Stockholm, Berlin and Malaga the same year. In 2018, New York’s Guggenheim Museum exhibition broke all attendance records. Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings brings her art to the southern hemisphere for the first time.

The transformation of af Klint from competent academic to inspirational mystical abstractionist is a result of the same ideas that influenced many of her contemporaries including Kandinsky, Mondrian, Klee and Malevich.

Rather than rewriting the history of art by slotting her in as a hitherto unknown great woman artist, it is probably more useful to consider these ideas and their impact on her art.

Scientific and mystical change

The scientific discoveries of the late 19th and early 20th century encouraged many to question the very nature of the universe.

In the 17th century, Isaac Newton discovered light was made of particles. In the early 19th century, Goethe’s Theory of Colours led many to see colour had spiritual and psychological powers. In the early 20th century, Max Planck demonstrated light particles had energy.

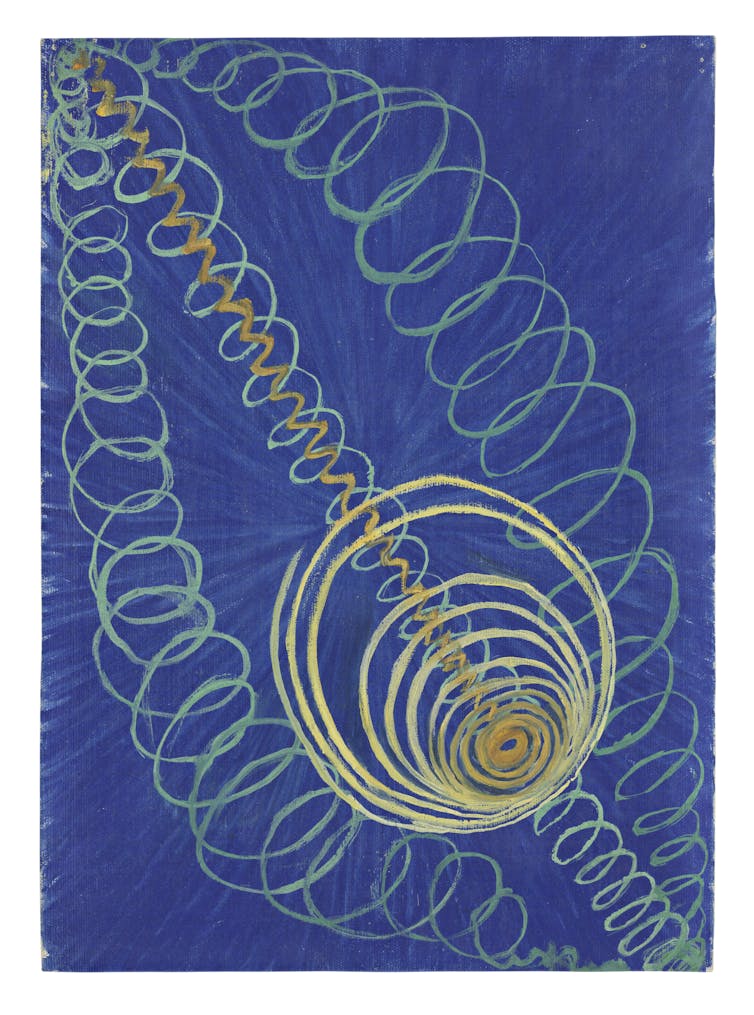

Hilma af Klint, Group 1, Primordial chaos, no 16. 1906-07. Oil on canvas, 53 x 37 cm. Courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Hak016. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden

Many began to think that, if the universe was more than it seemed, then perhaps there were other lives living on different astral planes. Perhaps it was possible for some to be mediums, opening themselves to communicate with spirit guides to these worlds.

At the end of the 19th century a new religion, Theosophy, appeared, incorporating both ancient wisdom and modern science.

Today, this may seem esoteric in the extreme, but Theosophy offered an apparently logical and modern system of belief. Its spread was global, and was a major factor behind the liberation of colour in early Australian modernism. In Sydney in 1926, the Theosophical Society was sufficiently mainstream to start a radio station: 2GB.

Read more: Clarice Beckett exhibition is a sensory appreciation of her magical moments in time

It is not surprising af Klint should become a follower. What is surprising is the power of the art unleashed as a consequence.

In 1896, she joined with four colleagues in a group they called The Five whose investigation of the spirit world included automatic drawing.

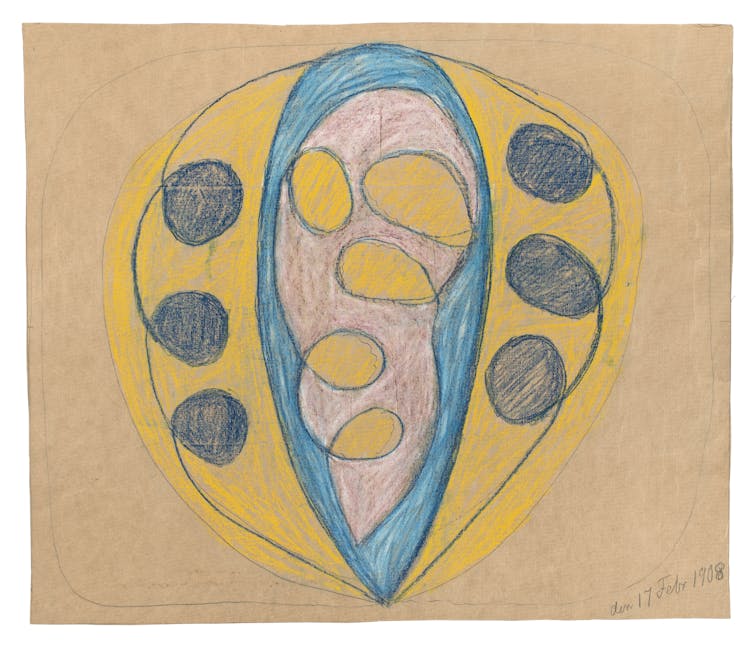

Hilma af Klint, Untitled, 1908. Dry pastel and graphite on paper. 52.5 x 62.6 cm. Courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Hak1258. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden

In 1906, her spiritual communications led to her spirit guide Amaliel “commissioning” a new series, The Paintings for the Temple. She later described this as “the one great task that I carried out in my lifetime.”

However, af Klint did not see herself as just a simple conduit for the spirits to control:

it was not the case that I was to blindly obey the spirits, but that I was to imagine that they were always standing by my side.

The first Paintings for the Temple were completed five years before Kandinsky proclaimed his revolutionary argument for abstraction in The Spiritual in Art.

In 1907 she painted her great series of works, The Ten Largest.

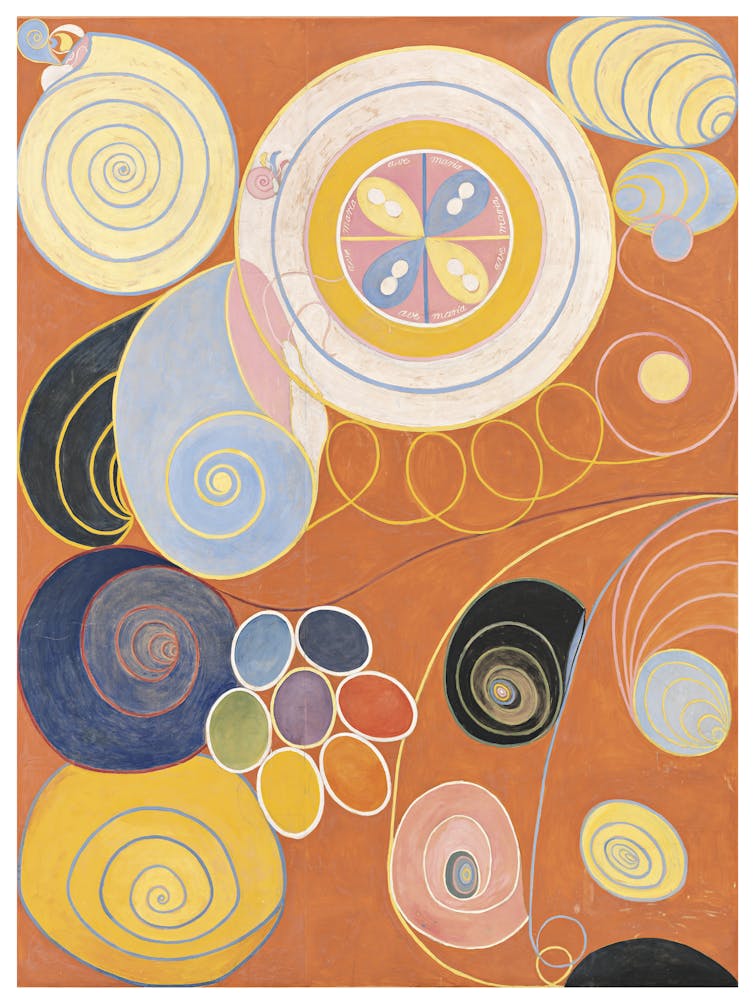

Hilma af Klint, Group IV, The ten largest no 3, youth. 1907. Tempera on paper mounted on canvas, 321 x 240 cm. Courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Hak104. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden

They are, by any measure, a magnificent study of the seasons of life. Elements of nature, geometry and mysterious writing are traced through juvenile floral blues to orange youth, mauves and yellows of adulthood, then in the seeds of old age where the red paint is all scumbled and thin.

Installation view of The Ten Largest at the Hilma af Klint: The Secret Painting exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, 12 June — 19 September 2021. Photo: Jenni Carter © AGNSW

The value in being forgotten

To understand both why her art developed the way it did, and why it was so little known for so long, it is probably worth considering the events of her lifetime and her own position.

Hilma af Klint was from an aristocratic Swedish naval family. During the first world war, Sweden’s position was armed neutrality, but she was only too aware of the carnage. Her Swan series, started shortly after the outbreak of war, pitches white swan against black as forms become abstracted, looping in harmony, dissolving into geometry and pure abstraction — until at the very end the two swans are locked together. Each contained elements of the other.

Hilma af Klint, Group IX/SUW, The swan, no 1. 1914-15. Oil on canvas, 150-150 cm. Courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Hak149. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden

In 1908, Hilma af Klimt showed the Paintings of the Temple to Rudolph Steiner. He failed to understand her work, and did not appreciate the way she saw herself as working with spirits.

This, as well as the burden of caring for her frail and blind mother, may be why she abandoned painting for four years. It may also be why she specified her art be kept secret until 20 years after her death.

There is also a more pragmatic reason. For all its studied neutrality, Sweden was very close to Germany as the Nazis assumed power: radical abstract art with mystical overtones could have caused problems.

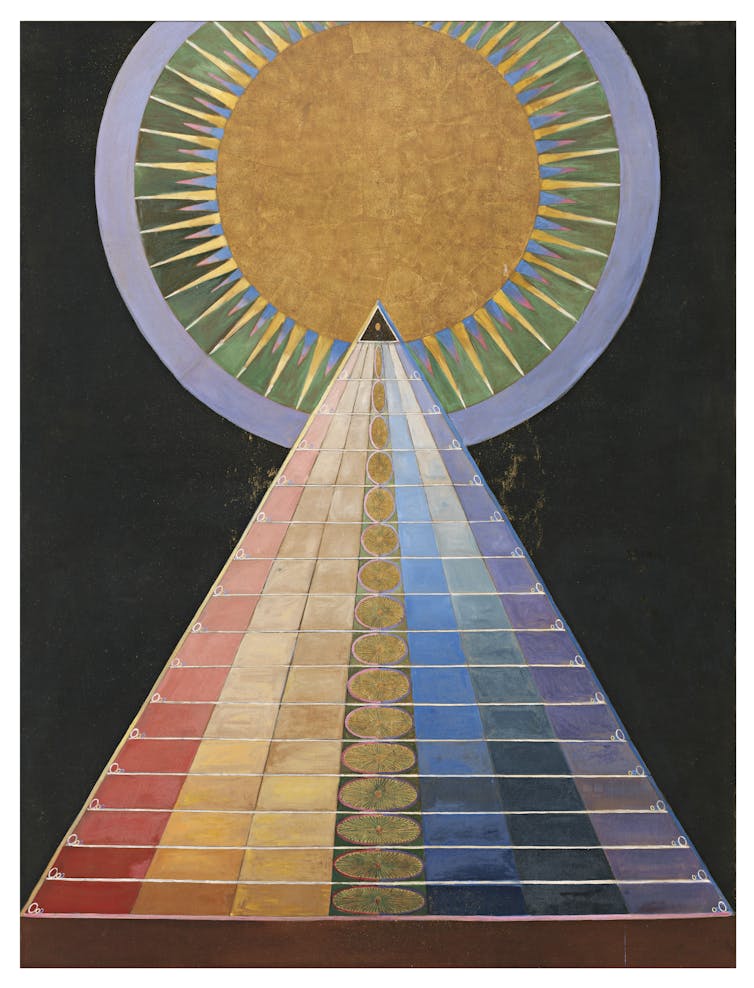

Hilma af Klint, Group X, Altarpiece, no 1. 1915. Oil and metal leaf on canvas, 237.5 x 179.5 cm. Courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Hak187. Photo: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden

Hilma af Klint died in 1944. In 1970, after seeing the riches of his aunt’s creative legacy, her nephew Erik offered her art to Sweden’s Moderna Museet. The gift was rejected out of hand when the director heard she was a mystic and a medium.

A year later Linda Nochlin published Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? — an essay ushering in a new era of scholarly reassessment of art by women.

It was perhaps fortunate this gift was rejected. Almost all her art is now owned by the Hilma af Klint Foundation, created by her family. It will never be scattered by the art market nor be the subject of speculation by dealers.

Instead, it is both a constant resource for scholars and for audiences to marvel at the meditative beauty of her forms, the incandescence of her colour and the way she opens eyes to new ways of seeing.

Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until September 19, then City Gallery Wellington from December 4.

Syndicated from www.theconversation.com. Joanna Mendelssohn is Principal Fellow (Hon), Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, The University of Melbourne. Joanna Mendelssohn has received funding from the Australian Research Council.

On Aug 17, 2021 Patrick Watters wrote:

Art often seeks to express truth that is beyond. Hilma’s once “hidden” abstracts seem to be expressing the oneness, the fusion, of the mathematical and the spiritual? }:- a.m.

Post Your Reply