Practicing the Art of Wonder through Radical Presence: Lessons from the Hummingbird

Published Summer 2021

“Is not beauty something that takes place when you are not?” — J. Krishnamurti, Ojai, California, 19851

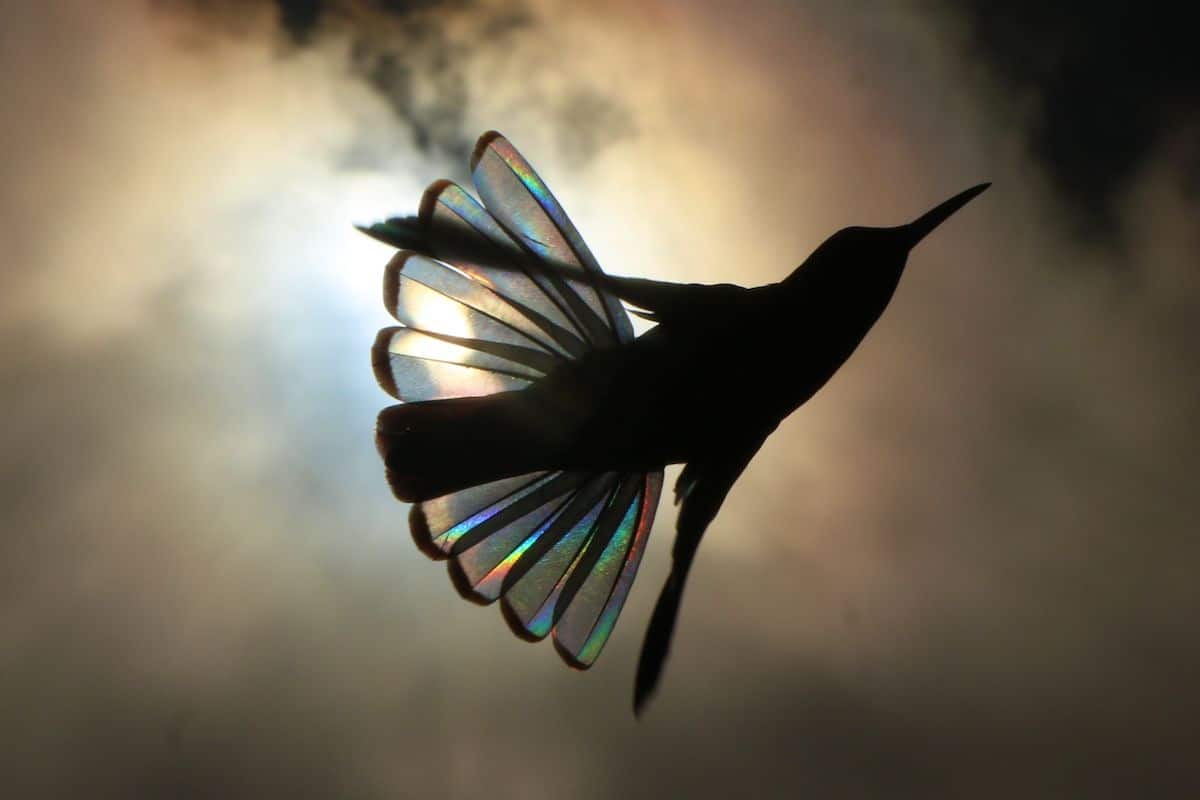

A Broad-billed Hummingbird hangs for a few seconds, not three feet away. The brilliant sapphire gorget flashes for an instant, and then the tiny bird is gone in a shot, his raspy cry fading like a lost thought into the oaks. I close my eyes and try to feel the impact that the hundreds of hummingbirds I’ve seen over the past few days have had on my psyche. The swirl of their presence, their diminutive size, their radiant color, their adroit quickness, their bickering flurries, all seep into me, and finally well up into awed appreciation, just for their being in the world. Past, future, and self fall away. In that moment, I’ve become the planet-as-human, in wonder at hummingbirds, feeling them as part of the splendor of life.

I am having this moment in one of the most diverse landlocked plant and animal communities in the world and I’m thinking about flight, how it might have come to be that life learned to transcend the bounds of gravity. I’m also thinking about energy, its sources, our need for it, and how access to it is integral to the flourishing of all of Earth’s community. These two preoccupations—flight and energy—didn’t rise up in me arbitrarily. The canyon I’m in, part of the Chiricahua Mountains in southeastern Arizona, boasts the highest concentration of bird species in North America. My love for birds is why I came here. And the relationship between flight and energy takes on particular meaning because of my third preoccupation: the bond between hummingbirds and flowers; there are fourteen species of hummers that frequent the canyon, the highest count anywhere in North America.

Few, if any, activities in the animal world are as energy intensive as flight. And no species of bird has used it so extravagantly as the hummingbird. No other bird has mastered backward flight. And hovering, something hummingbirds do with unparalleled grace, requires extremely rapid and energy-intensive wing movement. Other birds are more economical in their use of energy in flight, like swifts, for example, who have long slender wings that keep them aloft with minimal wing movement for weeks, even months at a time. And yet, hummingbirds hover, even when it exacts a high energy cost. Their reward is access to nectar, and lots of it.2

Few, if any, activities in the animal world are as energy intensive as flight. And no species of bird has used it so extravagantly as the hummingbird. No other bird has mastered backward flight. And hovering, something hummingbirds do with unparalleled grace, requires extremely rapid and energy-intensive wing movement. Other birds are more economical in their use of energy in flight, like swifts, for example, who have long slender wings that keep them aloft with minimal wing movement for weeks, even months at a time. And yet, hummingbirds hover, even when it exacts a high energy cost. Their reward is access to nectar, and lots of it.2

The hummingbird’s draw to nectar ignited a unique kind of co-evolution that has heightened the diversity of bird-loving (ornithophilous) flowers on Earth. The next time you stop to admire penstemon, or fuchsia, or similarly shaped flowers, thank the hummingbird for its love affair with nectar. That fascination drew out the forms and hues of a vast array of flower petals. The hummingbird’s singular obsession with nectar also gave rise to a dazzling array of color in the hummingbird’s plumage. The resemblance of a hummingbird’s feathers to the color in flowers’ leaves and blossoms is thought to help protect it from predators. This “coat of many colors” has incited a linguistic cascade in the human imagination in our attempt to capture its allure; a sample in English, out of more than 300: Long-billed Star-throat, Mountain Gem, Black-throated Mango, Fork-tailed Wood-nymph, Blossom-crown, Little Wood-star, Empress Brilliant, White-chinned Sapphire, Horned Sun-gem, Purple-crowned Fairy, the Magnificent, Black-hooded Sunbeam, and the Sparkling Violet-ear.

***

A Magnificent hummingbird veers out of the shadows. The chartreuse of his gorget shimmers. His crown and breast flare up in deep purple as the feathers refract under a flood of sunlight. He hangs, almost motionless for a few seconds, over a trumpet flower bush. In an age-old dance of enamorment, he visits flower after flower. I’m back from my preoccupations of mind and self, surrendering myself to wonder again.

Our own radical presence to what fascinates us elicits similar creativity to that of the hummingbird’s. To allow ourselves to be drawn toward what most deeply moves us is an embrace of Eros, a desire for union with the ground of our being. This communion of one being with another gives rise to further complexification, and thus to expressions of beauty never before seen on Earth. Our human capacity to be transfixed by beauty is the same evolutionary dynamic as the draw of hummingbird to flower. Expressed through human conscious self-awareness, communion reaches an order of complexity that in a word, becomes wonder.

Photo | Christian Spencer

To “become” wonder is to come into a state of radical presence. Embodying wonder means that we are feeling that which is most vital in our being. Rabbi Abraham Heschel wrote that to live the spiritual life means to live in a state of “radical amazement.” The origin of word radical, radicalis, means to “get at the root of things.” To be in wonder is to engage in amazement at the root of our being, the primary reality that we are Earth aware of herself, perceiving her own splendor. To truly take this in is to lose ourselves in a larger reality and gain a freedom beyond the small self.

Radical presence quiets the mind and opens us to what is; in so doing, it dissolves the illusion of separateness to which our minds adhere. As a practice of compassion (to “feel with”), radical presence opens us to the universal experience of pain and loss. Our hearts are not simply broken, but opened. When our hearts open, our feeling of reverence is not a mere concept. It is an experience of profound acceptance of the unique genius that has emerged within each being that shares our living planet.

What brings us most quickly into radical presence is a suspension of ego. To expand Krishnamurti’s quote at the beginning: “beauty is extinction of self, absorption by another subject. We forget ourselves in the face of fullness, grandeur, richness, dignity.” I like to refer to this as the “great enamorment,” the draw of being for being in the universe that gives rise to new life and novel forms, to creativity, in a word. Complete absorption by another subject shapes us, amplifying our identity beyond the small self to a greater, more inclusive Selfhood. We remember and feel our sense of belonging. And when our identity expands to a belonging to the Earth community, our dreams and our actions can become planetary in scope and scale.

So much of the destruction in our economic, political, environmental, and social systems has been driven by an ethos of self-interest, individualism, and isolation. Radical presence pulls us out of these narrow silos of understanding. To be in radical presence to another person—whether it is a human person, a hummingbird person, a salmon person, or the personhood of a forest—is to step into an ethos of mutuality. The human species has evolved to cooperate, in spite of what the ideologies of self interest have perpetrated on human consciousness. Radical presence opens the gateway to cooperation, synergy, and reciprocity.

To respond creatively to the challenges of planetary change today, we need both a functional story and a practice. The functional story, a cosmology, is one that narrates who we are as a species. The practice is one that repeatedly and continually renews our sense of that story on the physical, spiritual, and psychic levels of our being. For the first time, we have a story of our common origins in the Universe. That’s a gift of science, primarily physics, geology, biology, and astronomy. This scientific cosmology is still being interpreted by mythologists, cosmologists, educators, and philosophers into a meaningful cultural cosmology. Combine story (cosmology) with practice, and all areas of human interaction can better cleave to an Earth ethic. For instance, if our notion of democracy expands to a biocracy wherein all species have right to flourish, false dichotomies, such as that between social and environmental justice, begin to fall away.

How do we “become wonder” and come into radical presence? By opening ourselves to the mystery and numinous depths of the natural world through a practice of spiritual ecology. By reflecting every day on the fact that an emergent universe has resulted in something quite amazing: the appearance of a being through which the universe reflects on its own splendor. The human is the way through which the universe feels the glory in a storm, a pine forest, or the light bathing the face of a mountain range. For the first time, we have a story that can give us, as a species, a deep sense that we have a role in the universe. Perhaps that role is simply that we are here to celebrate splendor. We’re not just dropped down here, but have emerged from the planet herself. As we let ourselves be drawn to what we love, we both personalize and further evolution’s creative emergence.

The more deeply we sense the glory and absorb the multi-faceted story, the richer will be our experience, the more vivid will be our imagination, and the deeper will be our connection to the divine. It’s why species diversity and extinction are so important. Why should we care about the African elephant, the polar bear, or the Delta smelt? Because each being is a manifestation of the divine; and each is a one-time endowment of the evolutionary process. Once gone, they can never come again. When our breath is taken away by a 3,000 year old redwood or a seashore vista, the delicacy of a wildflower’s petal, or the burnt sienna of a salamander’s flesh in sunlight, we are the way in which universe revels in its splendor.

Often our sense of wonder, our joy, goes to sleep, or gets buried under the frantic searching of a mind that craves certainty and answers. But we can bring it back again through our breath, our attention, our heart beating. We quiet our minds, come back to ourselves, and let ourselves be sensitized to the shimmering intelligence all around us. In that place of surrender, we find the source of our wonder not only intact, but transformed.

References

[1] J. Krishnamurti, Beauty, Pleasure, Sorrow, and Love, Ojai Talks, audio, Harper & Row, 1989.

[2] Robert Burton, The World of the Hummingbird, Firefly Books, Ltd., 2001.

Syndicated from Kosmos the print and online journal for transformational thinking, policy and aesthetic beauty and collective wisdom. K. Lauren de Boer is a poet, essayist, and composer. He was executive editor of EarthLight, a magazine of ecology, cosmology, and spirituality for many years. He is currently visiting professor for the Integrative Learning Program in Eco-Cosmology for the Institute for Educational Studies at Endicott College.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On Jul 15, 2021 joanna wrote:

Reading this was like going to church. Thank you. I commune with the hummers every morning with my coffee on the patio. They greet me with their presence hovering just inches from my face and heart. What a way to start the day with awesomeness.

On Oct 29, 2024 Bharat Ram wrote:

Post Your Reply