Kolam: Ritual Art that Feeds a Thousand Souls Every Day

.png) Kolam and photograph by Kripa Singan

Kolam and photograph by Kripa Singan

Each dawn, millions of Tamil women create intricate, geometric, ritual-art designs called 'kolam,' at the thresholds of their homes, as a tribute to Mother Earth and an offering to Goddess Lakshmi. A Tamil word that means beauty, form, play, disguise or ritual design-- a kolam is anchored in the Hindu belief that householders have a karmic obligation to "feed a thousand souls." By creating the kolam with rice flour, a woman provides food for birds, rodents, ants and other tiny life forms -- greeting each day with 'a ritual of generosity', that blesses both the household, and the greater community. Kolams are a deliberately transient form of art. They are created anew each dawn with a combination of reverence, mathematical precision, artistic skill and spontaneity. Read on for one kolam practitioner's deeply personal exploration of this multidimensional practice.

My mother is standing at the wooden door to our house. It is almost 9 at night and she is beckoning to me urgently, gesturing that I come quietly, but quickly. She is peering through the glass windows set in the top half of the door, at someone, or something. I join her there and see an interesting sight. A bandicoot [1] is diligently eating what remains of the rice flour of the morning’s kolam. With the same regulated precision with which I drew the geometric design, the bandicoot is lick-nibbling the flour off the floor -- first the outer lines and curves, then the inner. She/he looks up momentarily, possibly sensing two humans a little distance away, watching with our eyes ever so slightly enlarged, and our startled, but soft smiles. We do not seem to be a threat, so she/he then bounces up to the lowest of the three steps that lead to the house, and proceeds to nibble at some more kola-podi (rice flour powder), from the corners. I had never quite seen bandicoots the way I now see them, since that night. Till that encounter, I had mostly considered them to be a nuisance, digging up various precious plants in my garden, gouging our clayey garden soil in patches, and uprooting young Citrus saplings -– huge rat-like, fairly ugly creatures with rough, bristly skin. But tonight, as they nibble at the kolam, they appear transformed. Softened by their hunger and their scavenging, and the vulnerability in their eyes as they pause to look upwards -- nose twitching, whiskers trembling. Tonight, they are clearly one of a thousand souls that a kolam seeks to feed [2], and they are wholly welcome to what they can take/eat.

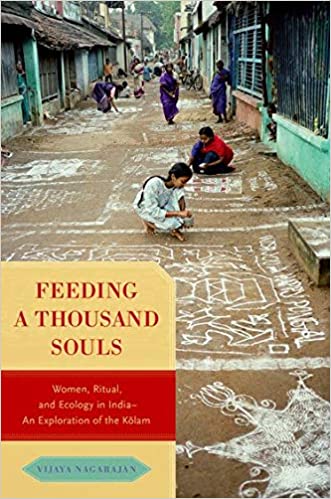

Kolams are sacred geometric designs drawn by Tamil Hindu women at the thresholds of houses and shops, and sacred trees and Hindu temples. They are meant to be drawn at two crucial times of transition – at the break of dawn, welcoming the sunrise; and at the gloaming of dusk, fare-welling the setting sun. In her part-scholarly, part-personal narrative book ‘Feeding a thousand souls’, anthropologist and folklorist  Vijaya Nagarajan explores what the kolam is and what it means/has meant to Tamil women, over millennia. Several Tamil women she meets and interviews are unequivocal in their explanation that kolams are drawn in the morning to welcome Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and beauty of all forms, be it material or spiritual, into our homes, and to ask forgiveness of Bhudevi (the Earth goddess) for all our sins of omission and commission through the day. This is what I was taught as well, as a child, when I first began to draw kolams in my grandmother’s home – that a kolam welcomes the goddess Lakshmi into the household.

Vijaya Nagarajan explores what the kolam is and what it means/has meant to Tamil women, over millennia. Several Tamil women she meets and interviews are unequivocal in their explanation that kolams are drawn in the morning to welcome Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and beauty of all forms, be it material or spiritual, into our homes, and to ask forgiveness of Bhudevi (the Earth goddess) for all our sins of omission and commission through the day. This is what I was taught as well, as a child, when I first began to draw kolams in my grandmother’s home – that a kolam welcomes the goddess Lakshmi into the household.

Reading Vijaya’s book, I recalled suddenly and vividly that we did draw kolams twice a day, when I was younger, in the late evenings as well, though I/most women in the city do not really do this at sunset anymore [3]. The explanation given by the women interviewed fascinated me -- that at sunset, we draw the kolam to bid farewell to Lakshmi, and to instead, welcome her older sister, Mudevi or Jyeshta in (Jyeshta means elder in Sanskrit, and Mudevi translates to the goddess of bad/unwholesome things). Mudevi is considered the goddess of sloth, languor and untidiness, and several women Vijaya interviews explain that as we wind down at sunset, these qualities are acceptable and needed, so we may move towards rest for the body. Discovering this breadcrumb about the kolam makes me fall in love with this practice all over again, as I seek in my own life, to not so much transcend dualities, as to embrace them all, and witness that most things pass, given sufficient time…

The kolam is not unique to Tamil women. Similar geometric designs composed of dots, curved lines, squares and triangles exist in several other states of India. Variously called rangoli in parts of North and South India, saathiya in Gujarat, maandana in Rajasthan, muggulu in Andhra Pradesh, alpana in West Bengal, pookalam in Kerala etc., these traditions appear to be as old as time and human existence in India itself. There are some subtle differences between these many practices, however. For example, the rangoli often uses colour powders, the pookalam is made with flower petals during the Onam festival and the alpana is largely confined to auspicious occasions and festivals. The kolam, however, is made every day using ground rice flour powder [4] at the threshold, that liminal space where the public and the private spheres of the household meet, collide and meld. A belief is that some of the prayers and goodness of heart that a woman exudes as she makes the kolam are transferred to the footsteps of those who walk over it through the day.

Reading that in Vijaya’s book brought a lopsided grin to my face as I remembered the many times I would wince as folks walked over a particularly well-executed and aesthetically-pleasing kolam I had made. I also remembered the many times I had walked in a zig-zag manner during my childhood, skirting and admiring the kolams, so as to not step on it and destroy it too soon. This was a different Chennai. A city that we then called Madras, without the insane traffic we currently possess, where pavements [5] paid host to not just elaborate kolams, but also to, amongst other things, weavers busy setting up the warp and weft threads of their hand looms, and cows who placidly chewed cud while belching noisily and sprawling luxuriously, together with their calves. There was space then -- to get off the pavement and walk on the road, without wondering if one would get run over in short order by a vehicle. It has been many years since the cows and weavers have largely left the city. Is it any wonder that the kolams have got a little smaller in size and now jostle for space with pedestrians, motorbikes parked haphazardly, and hawkers selling anything from chai to watermelon juice to cloth masks in this covid-era? And is it any wonder that I do not anymore skirt around kolams, though I do feel the smallest of twinges when I don’t, and I try to walk more gently over the more lustrous [6] ones? I console myself with the thought that stepping on them was an intention and invitation of the makers and diviners of this ritual art form…

Reading that in Vijaya’s book brought a lopsided grin to my face as I remembered the many times I would wince as folks walked over a particularly well-executed and aesthetically-pleasing kolam I had made. I also remembered the many times I had walked in a zig-zag manner during my childhood, skirting and admiring the kolams, so as to not step on it and destroy it too soon. This was a different Chennai. A city that we then called Madras, without the insane traffic we currently possess, where pavements [5] paid host to not just elaborate kolams, but also to, amongst other things, weavers busy setting up the warp and weft threads of their hand looms, and cows who placidly chewed cud while belching noisily and sprawling luxuriously, together with their calves. There was space then -- to get off the pavement and walk on the road, without wondering if one would get run over in short order by a vehicle. It has been many years since the cows and weavers have largely left the city. Is it any wonder that the kolams have got a little smaller in size and now jostle for space with pedestrians, motorbikes parked haphazardly, and hawkers selling anything from chai to watermelon juice to cloth masks in this covid-era? And is it any wonder that I do not anymore skirt around kolams, though I do feel the smallest of twinges when I don’t, and I try to walk more gently over the more lustrous [6] ones? I console myself with the thought that stepping on them was an intention and invitation of the makers and diviners of this ritual art form…

How old is the kolam as a ritual art form? This is an interesting question to ponder. The earliest documented references in Tamil literature and poetry to the kolam are the poems of the Vaishnava saint and child-poetess Andaal, who is widely accepted to have lived around the 7th-8th century CE. But kolam-like designs appear [7] in some of the Bhimbetka cave paintings of Central India, dated to the prehistoric Paleolithic and Mesolithic age and widely-accepted to be the some of the earliest signs of human life in India. Similarly, Vijaya in her book describes her visits to the adivasi Toda villages in the Nilgiris to see their kolams and how the Irula, Korumba and Kota tribals draw kolams in front of their sacred tree shrines, perhaps propitiating the guardian tree spirits or deities. Hence, the answer to how old the kolam is, appears likely to have tendrils of connections to the earliest inhabitants of the lands we now call India…

I first learnt to draw kolams when I was home for the summer holidays and staying with my maternal grandparents. Learning to exert the right amount of pressure between thumb and forefinger, so the kola-podi (rice flour powder) would flow out into smooth lines or curves, and not jagged, tremulous ones, seemed overwhelming at first. I remember being in tears almost at the impossibility of the task in the initial days! But gradually, like with all things, steady daily practice brought a surety of touch and an ease of fluid movement, and I began to greatly enjoy this tactile art, imbued with logical properties that I could straightaway perceive, such as symmetry and pattern recognition. Kolams have actually caught the fancy of mathematicians and computer scientists who have attempted to use it to further their studies of array grammars and picture languages [8]. They were first introduced to the western world as a form of ethnomathematics (the intersection of mathematical ideas and culture) by the research of Marcia Ascher [9]. In her book, Vijaya further explores the mathematical underpinnings of the kolam, focusing specially on symmetry, their nested, fractal nature, their connection to the concept of infinity, their use by computer scientists as both picture languages that help in the programming of computer languages and as array grammars that function as algorithms to generate graphic displays. Reading all of that, more than anything, what came to mind was how a dancer friend of mine who is dyslexic once remarked to me that she learnt more about geometric and arithmetic progression from drawing kolams and her dance practice, than she ever did during her formal schooling.

.jpeg) I went through an intense period in my pre-teen years when I became fascinated by kolams and badgered every older female relative who was available and willing, either at home or briefly visiting during the summer holidays, to draw kolams they knew, in my art book [10]. I would then copy them painstakingly using a stubby pencil and practice them the next day at the entrance threshold to the house. For some reason, this fascination waned a little through high school, and my kolam books gathered gentle dust, till my life trajectory shifted dramatically, in 2016. I was back home after many years and I was really looking to weave more hand and heart into my daily life, which had been suffused with the heady pursuit of being a scientist for close to a decade. On an impulse, one morning, I pulled out my kolam book and began again. My mother, slightly amused, was more than willing to cede one threshold to me [11].

I went through an intense period in my pre-teen years when I became fascinated by kolams and badgered every older female relative who was available and willing, either at home or briefly visiting during the summer holidays, to draw kolams they knew, in my art book [10]. I would then copy them painstakingly using a stubby pencil and practice them the next day at the entrance threshold to the house. For some reason, this fascination waned a little through high school, and my kolam books gathered gentle dust, till my life trajectory shifted dramatically, in 2016. I was back home after many years and I was really looking to weave more hand and heart into my daily life, which had been suffused with the heady pursuit of being a scientist for close to a decade. On an impulse, one morning, I pulled out my kolam book and began again. My mother, slightly amused, was more than willing to cede one threshold to me [11].

The more I drew the kolam every morning, the more they became an integral meditative practice. Funnily, they provided me with an anchor, to embrace both constancy and change, at the same time. Unless I was feeling unwell and needed rest, day in and day out, through light and mature summers, copious monsoons, dreary drought-like weather, or chilly winter dew, I made a kolam everyday. And every day, whether I felt pride and joy at a particularly aesthetic rendition or a tiny internal grimace at some flaws in execution, the kolam was half-smudged by the next day – nibbled at by ants, termites, squirrels, birds and bandicoots (depending on the season) and trampled over by the feet of visitors to the home, or even our own. More than a Vipassana practice on the cushion, the kolam was my visceral meditation on impermanence and gratefulness -- a reminder of the transient nature of life, and an act of gratitude for one more day of constancy and a somewhat stable routine.

There is another aspect of a daily kolam practice that I came to greatly cherish – its capacity to serve as a compass for my internal emotional state. On days I felt grounded, the lines came out smooth and steady, as I drew confidently and swiftly, dribbling the flour between my thumb and forefinger. On days I felt scattered or a little grumpy about something, there were miniscule kinks in the line. It was almost like the kolam was a mirror -- reflecting back to me my state of mind.

I draw a line and even if I haven’t noticed it before, I can now sense that some distinct emotion is flowing through me – whether it be anxiety, annoyance, sleepiness or excitement. I try to take a breath and let it go. Then I draw another line. And sometimes this one comes out more smoothly, more in flow. And onwards I go, most mornings...

There is another way in which a kolam practice serves as an internal compass -- in how I decide what kolam I wish to draw on a particular morning. First, there is the sweeping of the floor to be done. And depending on the time of the year, the seasonal leaf and flower litter that I am sweeping into the garden to serve as mulch, will vary. Right now, we have masses of soft, silky, limey-golden-yellow petals of the Sarakonnai tree/Amaltas (Cassia fistula) carpeting our threshold every morning. I sweep the flower litter and the remnants of the previous day’s kolam, together with small red ants that are furiously eating some of the rice flour, into the garden. Sometimes, there is a garden snail clinging to the steps and I dislodge that as well. Sometimes, especially after the monsoon rains, there are lots of millipedes milling around. I try to be gentle, so as to not kill any of the creatures. I am mentally whispering to them – please wait, there will be fresh rice flour here soon. I then splash water over the threshold and use a coconut frond broom to plaster the wetness all around and remove any water puddles that may be left behind. Traditionally, in the villages, this would have been done with cow dung diluted into the water, but like I said before, the cows are mostly gone from the city. So water will have to suffice. Then quickly, while the floor is still wet, I bend down and wonder what pattern feels like it wants to be drawn today.

A woman loops the pullis (dots) in one continuous thread of lines with precision. Caption and photograph by Anni Kumari.

A woman loops the pullis (dots) in one continuous thread of lines with precision. Caption and photograph by Anni Kumari.

I have two broad choices around patterns available – called pulli/shuzhi kolam (where dots are laid out in a grid and lines/curves are drawn either connecting the dots, or flowing in the spaces around and betwixt the dots) or a padi/katta kolam (where a geometric design is drawn without a grid of dots; using lines, curves and other motifs). Even in the first category of kolams, I can choose to draw kolams that connect the dots, and use natural motifs such as the lotus or other flowers, leaves of the banana or mango, fruits or vegetables such as the bitter gourd or cluster bean, birds such as the swan, duck or peacock, butterflies, and so on and so forth. Or I can draw a labyrinth kolam where the curves flow between the dots.

In the few minutes while the floor is still wet (and sometimes, in fact, immediately after I wake on some days), I am wondering what feels like it wants to be expressed today. Some days, I draw the lotus variations, especially on days when troubles and slush seems awash in my life, and I want to hold to inspiration, and a reminder of how lotuses bloom in the muck. Some days, I decide I need to actively practice gratitude for what feel like bitter events in my/our collective societal life, and then I might draw the bitter gourd fruit kolam -- to remind myself that the bitter cleanses you out, if you will let it, and makes you available for holding more sweetness. Some days, I am feeling more connected to the wonders of the universe and the infinite synchronicities of life, and then I draw one of the endless variations possible of the labyrinth kolams, where curves begin at one place, and then loop and curve and swerve, only to reconnect again at the beginning. The kolam on these days is a talisman. It reminds me that though I do not always see the patterns of meaning in my life, because I am too close to the ground of my experience, when I step back, they exist. And sometimes, it needs time and patience, and waiting, for the full pattern to be unveiled. And there are days too, when I feel blank, when I am not sure what I want to draw. On those days, I draw whatever first comes to mind, even if it is arising by some muscle of habit, trusting that this is what needs to be expressed in the morning.

In her book, Vijaya explores how the kolam is meant to signal the well-being of the household to the community, since it is not made when the women is on her period, or there is illness or death in the house, for example. While there are inevitable and likely convincing arguments and petitions to be made about ritual purity in the context of this proscription, this was the manner in which, in days of yore, in the absence of telephones and modern communication, neighbours knew that someone might need help in a particular house. A missing kolam suggested that something was afoot and this was the time for neighbourly generosity or assistance. It’s interesting to me, that in cities like mine, where the kolam is not made everyday in every Hindu household or is often drawn by the household-help and not the women of the household, several of these signaling aspects of the kolam have been lost. When I was younger and I was asked to not come into the household temple/shrine area when I was on my period and I felt insulted and treated as impure, I was glad to be able to rebel and make the kolam in the outermost threshold, even if I was menstruating. Nowadays, I feel differently about this. I am sometimes glad for a little extra rest when I am on my period and having cramps, and the morning kolam exercise routine of squatting and stretching and moving around as one draws the design feels like an imposition and not sweet, rebellious freedom! So on some days, if I feel unwell, I just let the previous day’s kolam be, and watch as it fades out slowly over days, until I am ready to begin again...

I end these meditative meanderings of my mind on the subject of kolams with an invitation to you, the reader. Do you have a practice of art-making or ritual -- or maybe both, like in the case of kolams -- which grounds you in the immediacy of life? If yes, please cherish and honour it, for what it gives you and others. And if not, I wish the discovery of such a practice for you, with all my heart.

[1] Online encyclopaedias tell me that what we call the bandicoot in India is more accurately called the lesser bandicoot or the Indian mole-rat and they are unrelated to the true bandicoots which are marsupials. The local Tamil name is ‘perichali’ which translates as large rat. What is a little hilarious is that the name ‘bandicoot’ comes to English from the Telugu name for these rats, ‘pandikokku’ which translates to ‘pig-rat’ for the grunts they emit. And these are not the true bandicoots apparently!

[2] Feeding a thousand souls; Chapter 11; Vijaya Nagarajan

[3] The only time in recent years that I felt compelled to make the kolam at sunset was when we experienced a block in our sewer lines at home after what was likely the city corporation not pumping the sewage lines on schedule, given the chaos of the covid-19 pandemic. While we were waiting for the city corporation to come the next morning and run their sewage de-clogging machine, I prowled the house around sunset, feeling frustrated at not being able to ‘solve’ this problem immediately and thinking of my (and the ‘civilized’ human community’s) relationship to human waste and the emotions it generally evokes. Suddenly, I could think of nothing better to do, to honour both my emotions, and as a prayer for divine help, than making the kolam at sunset. “I see your place in our world, Mudevi,” I whispered internally, as I bent down to make the kolam.

[4] The kolam is nowadays, often and unfortunately, made using powdered limestone (stone powder) preferred for the ease and brightness of strokes that one can draw with it. Drawing with rice flour requires some practice, patience and dexterity, all of which are apparently in short supply in these times. Limestone powder cannot feed a thousand souls, needless to say…

[5] In India, we use the term pavement to refer to what Americans call the sidewalk

[6] Vijaya uses the translated adjective ‘lustrous’ in her book to explain what qualifies a kolam as exceptional and I believe it really hits the mark. The Tamil women she interviews tell her that it is something akin to the kolam exuding a soft grace, a sense of balance, proportion and shining beauty.

[7] Sacred Plants of India, page 11; Nanditha Krishna and M. Amirthalingam

[8] See https://www.cmi.ac.in/gift/Kolam.htm for an early example of this work

[9] Ethnomathematics: A multicultural view of mathematical ideas; by Marcia Ascher

[10] My art book consisted of several loose sheafs of white paper that I had hand-bound using needle and thread. The binding still holds after all these years.

[11] Kolams are often drawn at several, successive entrance thresholds to the house. The outermost threshold where the public pavement and the private gate to the house meet is an important locus, but so is the inner threshold where the steps lead into the house (if these are different, as they happen to be for us). My mother gave me this ‘inner’ threshold for my daily practice!

***

For more inspiration, join this Saturday's Awakin Call with Vijaya Nagarajan, the author of "Feeding A Thousand Souls." RSVP info and more details here.

Gayathri Ramachandran uses the label ‘permaculture gardener by hand and heart, and scientist by head’ to succinctly describe herself! She has spent the past several years, designing and working in her urban permaculture garden with more than 150 species of native trees, shrubs, herbs, and edible medicinal 'weeds', adopting various methods to move her family household towards zero-waste, working in various communal tree planting projects, conducting tree walks, practicing and sharing NVC, volunteering with ServiceSpace, meditating, and drawing kolams! All of these activities have been undergird by a common motivation of learning to listen more deeply, and cultivating the field for what is ripe for emergence.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

4 Past Reflections

On Sep 24, 2021 D Ellis Phelps wrote:

How very lovely to know about this ritual art. I teared at the end, at this blessing:

Do you have a practice of art-making or ritual -- or maybe both, like in the case of

-- which grounds you in the immediacy of life? If yes, please cherish

and honour it, for what it gives you and others. And if not, I wish the

discovery of such a practice for you, with all my heart." Thank you.

On May 21, 2021 Rajalakshmi Ram wrote:

Loved it! You may want to check a documentary made by my (then-14 year old) son on Kolams which was screened in the Tel Aviv Film Festival. It is sad this art form is dying or remains merely a symbol depicted in sticker Kolams in the cramped apartment corridors! But that it is extremely meditative exercise is so true!

-Raji

On May 20, 2021 MI wrote:

Thank you! This is deeply beautiful, inspiring and significant.💞

On Mar 14, 2022 Dr.Cajetan Coelho wrote:

Generosity and magnanimity have brought human beings and all living beings thus far. When I was hungry, you gave me to it - declare Scriptures of different cultures. "The Tamil kolam is anchored in the Hindu belief that householders have a karmic obligation to 'feed a thousand souls.' By creating the kolam with rice flour, a woman provides food for birds, rodents, ants, and other tiny life forms - greeting each day with a ritual of generosity, that blesses both the household, and the greater community" - Gayathri Ramachandran

Post Your Reply