Kahlil Gibran on Befriending Time

I have been thinking about time lately, as I watch the seasons turn and wait for a seemingly endless season of the heart to set; I have been thinking about Ursula K. Le Guin’s lovely “Hymn to Time” and its kaleidoscopic view of time as stardust scattered in “the radiance of each bright galaxy” and the “eyes beholding radiance,” time as a portal that “makes room for going and coming home,” time as a womb in which “begins all ending”; I have been thinking about Seneca, who thousands of seasons ago insisted in his Stoic’s key to living with presence that “nothing is ours, except time.”

And yet there is something odd about this notion of time as property. We are asked to give things time; we speak of taking time — time off of something, time toward something. But how do we give or take this fine-grained sand that slips through the fingers the moment we try to cup it? Perhaps time is not so much the substance in the hand as the substance of the hand; perhaps Borges was right in his sublime refutation of time: “Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire which consumes me, but I am the fire.”

How, then, do we befriend the thing that both destroys us and is us?

That is what poet, painter, and philosopher Kahlil Gibran (January 6, 1883–April 10, 1931) explores with great subtlety of sentiment in a passage from his timelessly rewarding 1923 classic The Prophet (public library), which also gave us his abiding wisdom on the building blocks of true friendship, the courage to weather the uncertainties of love, and what may be the finest advice ever offered on parenting and on the balance of intimacy and independence in a healthy relationship.

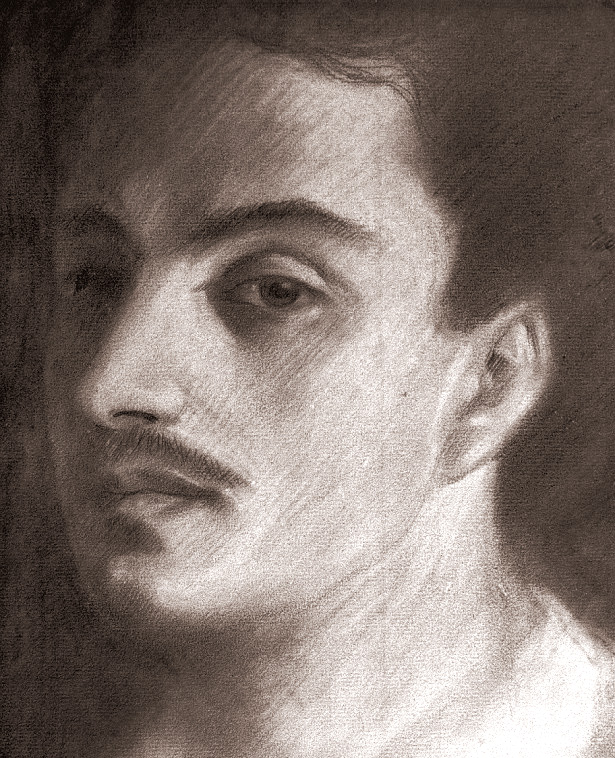

Kahlil Gibran, self-portrait

When an astronomer beckons Gibran’s protagonist to speak of time, the Prophet responds:

You would measure time the measureless and the immeasurable.

You would adjust your conduct and even direct the course of your spirit according to hours and seasons.

Of time you would make a stream upon whose bank you would sit and watch its flowing.

Yet the timeless in you is aware of life’s timelessness,

And knows that yesterday is but today’s memory and tomorrow is today’s dream.

And that that which sings and contemplates in you is still dwelling within the bounds of that first moment which scattered the stars into space.

Art by Lia Halloran from A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader. Available as a print.

In a sentiment that calls to mind Patti Smith’s elegant meditation on time, transformation, and the seasons of the heart, he adds:

And is not time even as love is, undivided and paceless?

But if in your thought you must measure time into seasons, let each season encircle all the other seasons,

And let today embrace the past with remembrance and the future with longing.

Complement with Gibran on silence, solitude, and the courage to know yourself, then time travel a century ahead with the fascinating contemporary neuropsychology of how time perception modulates our experience of self and a touching recording of Neil Gaiman reading Le Guin’s ode to timelessness to his 100-year-old cousin.

This article is reprinted with permission from Maria Popova. She is a cultural curator and curious mind at large, who also writes for Wired UK, The Atlantic and Design Observer, and is the founder and editor in chief of Brain Pickings.

On Jan 14, 2020 bmiller wrote:

I often refer back to an observation by Ernst Mach (one of the founders of Quantum Physics): “It is impossible to measure the changes in things by time. Rather, time is an abstraction at which we arrive by the changes in things.”

It seems “time”, like “color” or “sound”, is an experience, not a thing that is external to and independent of our perception. For example, there is no color in the universe, only differing wavelengths of electromagnetic energy. The 'red’ or ‘green’ is an experience concocted in our brains in order to distinguish them. The passage of time is a similar phenomenon.

Post Your Reply