Change the Worldview, Change the World

Forty years after Thomas Berry’s “The New Story,” new generations are seizing on the power of narrative.

I was sitting in a classroom in Assisi, Italy, with one of the leading environmental thinkers of our time, and he was talking about the power of story. “It seems that we basically communicate meaning by narrative,” he said. “At least that’s my approach to things: that narrative is our basic mode of understanding.”

In that summer of 1991, Thomas Berry (1914—2009) was a 77-year-old sage; a Catholic priest—though never quite comfortably—a cultural historian, and a scholar of world religions, retired from teaching but at the height of his intellectual and prophetic powers. His central focus was addressing the deep roots of the ecological crisis.

As he spoke poignantly of what was being lost—the mass extinction of species and the accelerating devastation of the biosphere—Berry told us, “The difficulty that we’re into has come, to a large extent, from the limitations and inadequacies of our story. And what we need, I think, and what we really have, is a new story.”

As a 21 year old college student who didn’t know much, this was more than enough to radically expand my consciousness. I had never thought about the concept of “the power of story,” or that we ‘know’ things by way of story, or that our ecological crisis stems from our underlying worldview. I had felt it, but had never been handed these words and ideas as tools with which to think.

A couple years earlier, I was a teenager bored with high school when I had been caught and inspired by The Power of Myth, Bill Moyers’ series of interviews with comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell. While evading homework, I read Campbell’s Myths to Live By. But Berry’s work was something different.

Where Campbell anticipated that the mythology of the future would deal with the Earth as a whole, and would likely draw on the photographs of Earth from space as a mythic symbol, it seemed to me that Berry was already weaving just such a mythos. In Berry’s view, our new understanding of the universe and the Earth—the story of galactic emergence and development which had been gradually glued together by 20th-century astronomers and physicists like a cosmological collage—could provide a new sacred origin story, a cosmological homecoming for modern culture. “It’s enormously important for us to know the story of the universe,” Berry told us in Assisi, “and it’s the only way in which we’re going to know who we are.”

For Berry, it all came down to cosmology—the basic worldview of a culture: its foundational story of how the world came to be and how it got to be as it is now, and how we, as humans, fit into it. To address the deep underlying causes of the industrial-capitalist-corporate destruction of the biosphere, we had to examine our worldview.

In Berry’s view, a central cause of the West’s ecological hostility was its separation from nature—a separation that was at once spiritual, religious, psychological, emotional, intellectual, and philosophical. The root of the eco-destruction was an anthropocentric (human-centered) Western worldview that saw an existential gulf, a “radical discontinuity,” between the human and natural worlds.

Despite being a Catholic priest, Berry (like Lynn White Jr. before him) was unsparing in his environmental critique of Christianity. The historical orientation of the Christian tradition—its mandate to subdue and conquer nature, its focus on redemption from a “fallen” world, and the priority placed on a transcendent divinity—all served to alienate humanity from the cosmic-Earth process that gave us being.

In contrast to the Indigenous and Eastern cosmologies expressed in the Native American, African, and Asian traditions Berry taught to his students as founder of the History of Religions program at Fordham, the Western worldview generally saw humans as separate from the Earth and cosmos. And not only separate, but superior, with—as Berry noted ruefully—“all the rights and all the value given to the human, and no rights and no value given to the natural world.”

When this anthropocentric orientation in Western religion and thinking merged with the “new mechanical philosophy” of Descartes and Bacon in the 17th century, in which nature was viewed as a soulless machine, the stage was set for the modern worldview. Human arrogance, capitalist logic, and industrial-scale destruction was unleashed on a desacralized planet. The living community of Earth’s biosphere, which created and sustains us, was reduced to resources for use by the human, dead material to fuel endless “growth,” profit, and “progress.”

To stop this assault on the Earth, Berry told us in Assisi in 1991, requires recognizing that our cultural story is dysfunctional. To change the world, we have to change the worldview.

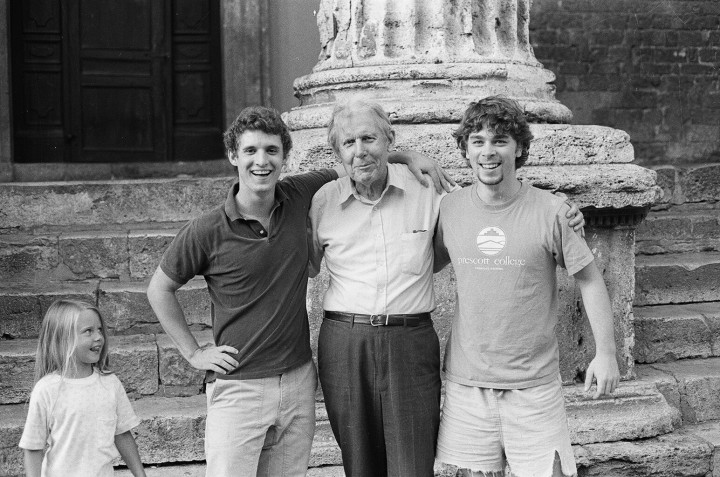

The author, Thomas Berry, and Stephan Snider in Assisi, Italy, in 1991.

The author, Thomas Berry, and Stephan Snider in Assisi, Italy, in 1991.

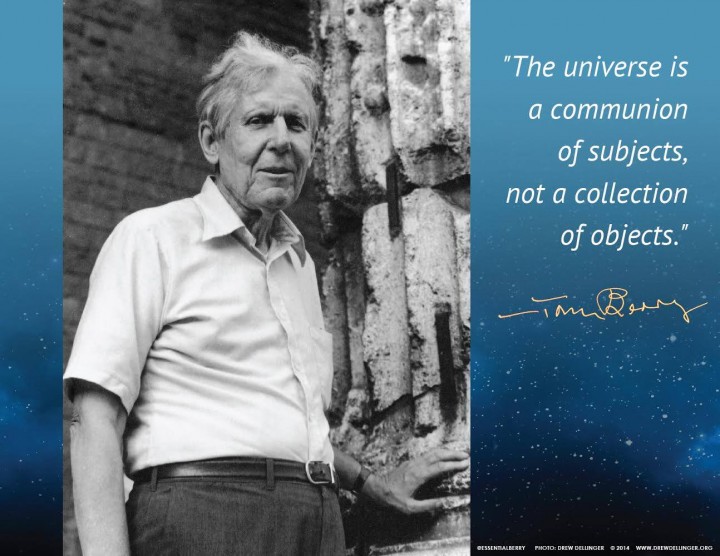

Thomas Berry in Assisi, Italy in 1991 (photo: Drew Dellinger)

Thomas Berry in Assisi, Italy in 1991 (photo: Drew Dellinger)

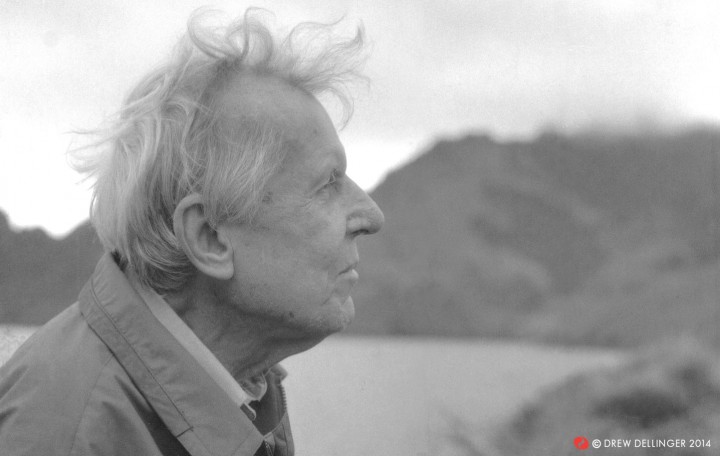

Thomas Berry in Ecuador in 1993 (photo: Drew Dellinger)

Thomas Berry in Ecuador in 1993 (photo: Drew Dellinger)

The New Story

Thirteen years earlier, exactly 40 years ago this year, Thomas Berry wrote and published a groundbreaking essay titled, “The New Story” (1978). After publishing books on Buddhism and The Religions of India earlier in his career, in the 1970s, Berry’s writing took a turn. Increasingly distressed by the destruction of the planet, he penned, from his home in Riverdale, New York, a series of essays—known as the Riverdale Papers—that explored the role of worldview and spirituality in relation to ecology and environmentalism.

“The New Story” began with sentences that would become an iconic expression of Berry’s insight:

“It’s all a question of story. We are in trouble just now because we do not have a good story. We are in between stories. The Old Story—the account of how the world came to be and how we fit into it—is not functioning properly, and we have not learned the New Story.” [original version, 1978]

A decade later, “The New Story” was republished in Berry’s first collection, The Dream of the Earth, along with 15 other essays, and his cosmological vision found a wider global audience. In the words of religious scholars (and former students of Berry) Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, “‘The New Story’” was “the culmination of a lifetime of Berry’s reflections on the growing ecological crisis and what new paradigm would be essential to counteract the devastating power of extractive and consumer economies. This new story, he felt, could begin to break through the modern view of materialism and reductionism that had objectified nature primarily as a resource for human use.”

Berry’s vision—sometimes referred to as the “New Cosmology”—was part of a wider movement within fields emerging in the 80s and 90s such as eco-philosophy, ecological spirituality, and ecopsychology. Proponents of these ideas questioned the fragmented worldview of modern culture. Cosmologist Brian Swimme worked closely with Berry and expressed this new cosmological vision in his books, The Universe is a Green Dragon and The Hidden Heart of the Cosmos. Radical theologian Matthew Fox critiqued the modern sense of disconnection and separation inherited from the “Newtonian ‘parts’ mentality,” Cartesian dualism, and reductionism.

Authors and activists Charlene Spretnak and Joanna Macy emphasized the practical consequences of our faulty societal story. “In the absence of any comprehension of the sacred whole,” wrote Spretnak, “meaninglessness and destruction are as acceptable as anything else to many people,” while Macy noted the relation between politics and cosmology, stating that a “sense of connection with all beings is politically subversive in the extreme.” Sister Miriam Therese MacGillis gave hundreds of presentations explicating Berry’s perspective on ecology, cosmology, and the New Story.

After publication of The Dream of the Earth, Berry continued to travel widely, teaching and speaking at conferences, universities, religious communities, and gatherings across the United States, United Kingdom, Europe, Canada, the Philippines, and beyond. In 1992 he coauthored The Universe Story with Brian Swimme and, in his last years, he published three more collections of essays, including The Great Work (1999) and The Sacred Universe (2009). By the time of his death in 2009, Berry was widely admired as one of the most influential, profound, evocative, and effective environmental writers of his day. And “while many ignored his warnings over thirty years ago,” state Tucker and Grim, “now his insights about the religious character of the environmental crisis continue to be prescient.”

Unlearning and Relearning the Elemental Stories

Twenty-eight years after writing the essay, “The New Story,” when I interviewed him in 2006, Berry was still grappling with the significance of cosmology and worldview. “It’s not easy to describe what cosmology is,” he told me. “It’s neither religion nor is it science. It’s a mode of knowing.” “The only thing that will save the twenty-first century is cosmology,” he said as we had lunch in North Carolina on a December day. “The only thing that will save anything is cosmology.”

Four decades after Berry wrote “The New Story,” his insights may be more relevant than ever. In the years after I first studied with him that summer in Assisi, I continued to reflect on story, as well as the links between social justice, ecology, and cosmology. It seemed to me that worldview was a key in all of these areas and was one of the connections between them.

Throughout the 20th century, racist and sexist policies and practices were supported by narratives operating in families, schools, workplaces, and the media, as well as in political, economic and legal/judicial institutions. The civil rights movement of the 50s and 60s, and the feminist/womanist movements of the 60s and 70s can be seen, in part, as massive re-storying on a culture-wide level.

Gender, like race, is a social construction, which is to say, a story. And the stories of sexism and racism that have cast such a pall over our history and our present illustrate the power of worldview and narrative in generating and maintaining systemic oppression. Stories become structures, systems, policies, and practices that have profound consequences on the bodies and in the lives of people in targeted communities.

Can we not see systemic racism, sexism, and other oppressions as functions of the same dominant worldview that is destroying the Earth? Settler colonialism at planetary scale? When I interviewed Berry in 1996, he told me, “If a particular society’s cultural world—the dreams that have guided it to a certain point—become dysfunctional, the society must go back and dream again.”

Yet the pervasive worldviews of white supremacy and misogyny continue to undermine our efforts to build justice, community, and democracy in the United States. Every week, as another unarmed Black man is shot by police or a woman is killed by a domestic partner, we see flawed stories turn lethal in seconds. The #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo and #TimesUp movements are challenging and transforming racist and sexist worldviews in powerful ways.

Dysfunctional dreams. Problematic stories. Distorted worldviews. Can we not recognize these at the root of not only ecological issues, but also social injustices such as white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism?

Perhaps no recent event illustrates the current clash between worldviews better than the Indigenous-led resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline in Standing Rock, North Dakota. Even mainstream media has used the word ‘worldview’, to recognize that this is not simply a conflict between activists and fossil fuel corporations, but fundamentally a clash of cosmologies.

Morning Ceremony at Standing Rock. Photo: R. Fabian

Morning Ceremony at Standing Rock. Photo: R. Fabian

On one side stands arrayed police forces representing the capitalist, industrial, corporatist worldview that sees nature as a resource to be exploited—a distorted dream driven by maximizing profits, regardless of consequences for people, communities, the biosphere, and future generations. On the other side is an Indigenous cosmology in which Water is Life, Earth is Mother, and reverence, respect, and reciprocity are paramount.

On one side is a worldview and legacy of systemic racism and mistreatment of Native peoples for centuries, in which, as Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “the ultimate logic of racism is genocide.” On the other side is a worldview of cosmological egalitarianism in which nature is holy and every being is sacred.

On one side is the “old story” of Western culture: a mythos of separation, disconnection, and anthropocentrism—of hierarchy and domination, in which division, exploitation, and oppression are the norm. On the other side is the “original story” of Indigenous traditions, a cosmology of community and connection.

The Water Protectors at Standing Rock challenged much more than a pipeline. They confronted the cosmology of the modern world and its destructive, unjust economy. Like the movement for Black Lives—which also is a direct challenge to 500 years of a white, racist worldview—the visionary resistance at Standing Rock may help guide our way into future. By connecting ecology, social justice, and worldview and using the power of spirituality, dream, story, art, and action, these movements bring forth—in practice and politics and society—what is needed most: a cosmology of interconnectedness.

The New Story of our times will be a multiplicity—a kaleidoscope of stories. As the writer and critic John Berger has said, “Never again will a single story be told as if it is the only one.” Long-silenced voices will continue to come to the fore. The stories needed most are emerging from the youth of Ferguson, Baltimore, Standing Rock, and Palestine rather than from the narrators of the status quo. From this diverse chorus, larger themes are taking shape, with recognizable contours bending toward justice and ecology.

We need stories that expose the lies of systemic racism, misogyny, heterosexism, colonialism, and capitalism. We need stories that stand up to fascism and authoritarianism, and stories that expand democracy.

We also need stories that connect us to the majesty of the galaxies and the depths of the ocean, stories that remind us who we are.

We need stories that stop abuse and create justice. Perhaps most of all, in this moment of widespread poverty and injustice, climate crisis, and mass extinction, we need stories that build movements.

In 2018, we seem, in some ways, farther than ever from the dream of a new story, with a level of political polarization that seems to fracture even our sense of common reality. Yet, if the possibility remains that we might heed Thomas Berry’s advice and “reinvent the human…by means of story and shared dream experience,” then now would be the time for massive, creative action. We owe it to the children of the future and the entire Earth community. As Berry wrote in his essay 40 years ago, “no community can exist without a unifying story.”

This article is syndicated from Kosmos Journal. Their mission is to inform, inspire and engage individual and collective participation for global transformation in harmony with all Life, by sharing transformational thinking and policy initiatives, aesthetic beauty and collective wisdom. Drew Dellinger, Ph.D., is an internationally known speaker, writer, poet, and teacher whose keynotes and poetry performances—which address ecology, justice, cosmology, and interconnectedness—have inspired minds and hearts around the world.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On Sep 19, 2018 Tiffany Schettle wrote:

I think in many ways we have the stories, and have since ancient times, but they tend not to be the voices that are Heard. If we all make an effort to uplift voices other than those of privilege then the narrative will shift. It's one reason why I make an effort to support the work of female authors, especially with an indigenous orientation. They are telling the stories and have been for millennia. The question remains if we are Aware enough to seek them out and Listen. Then share them with others. It's one of my Conscious, living reparations.

On Jul 29, 2020 Suzanne Taylor wrote:

For a comment this time around, with the republication of this piece, here's a podcast I did just before COVID with Brian Swimme, my super-hero: https://suespeakspodcast.co...

Post Your Reply