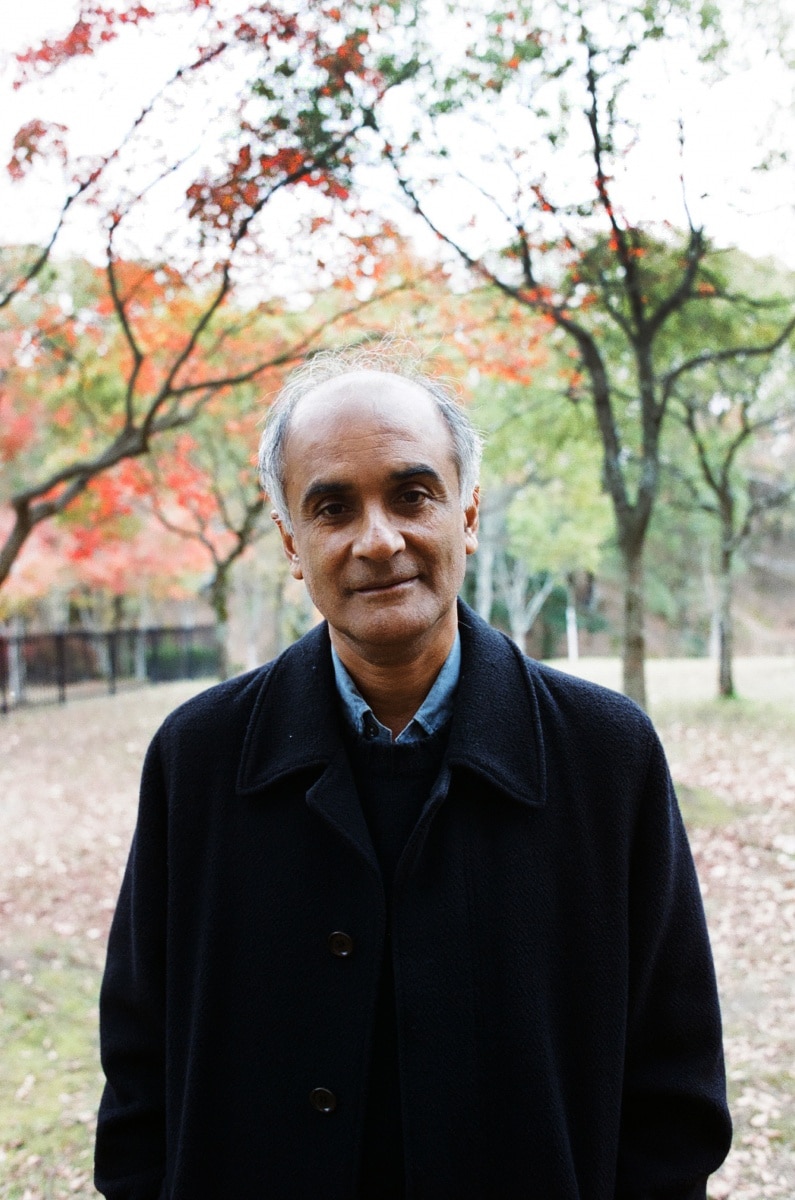

Pico Iyer Chooses Stillness

NATHAN SCOLARO: So I wanted to begin by asking you what thoughts you’ve been having lately. What’s been on your mind?

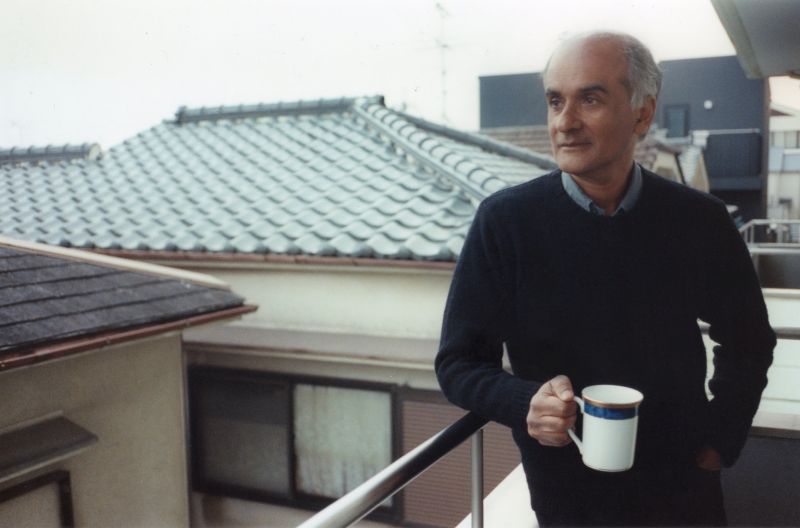

PICO IYER: Well, after a very crowded and congested year, I’ve managed to steal the last two weeks in almost absolute silence here in Japan. So I suppose I’ve been thinking about the folly of knowing, the virtue of seeing how little we know, and the beauty of just taking a deep breath. Which I’ve written about before, but I haven’t always practised! I’m getting to spend just a few days reading, writing, taking long walks, playing ping-pong every day. And sitting on my terrace in the blazing November sunshine, usually with a cup of tea and a few sweet Japanese tangerines and a good book. And the deeper the conversation with the book, the better the questions I come out with at the end. So somehow my mind has been going back to the fact that I never trust what I can explain.

“You never trust what you can explain.”

In other words, as I go through the autumn of my own life, I realise that everything essential in it has happened without a reason. I have my own little plan that I’m trying to foist on life, but life has a much wiser and more inscrutable plan that it’s foisting on me! And really the commonsensical thing for me would be to defer to life’s plan because it almost certainly arises from a deeper logic than my own. For example, why did I choose one woman, who became my wife, from among tens of thousands of other beautiful women of the same age in Kyoto? Why did I choose to live in Japan of all the many places I could be in the world? Almost everything that’s happened to me has come by chance. When I was a young man I thought so much about how I could script my life and go in this direction. And it never worked out that way—to my delight and benefit.

Well I love that. How did you come to live in Japan?

So I’m talking to you from my two-room apartment in rural Japan. And the reason I live here is that I was travelling to South East Asia for the first time in my twenties while living in New York City. And I had an unwanted 16-hour layover near Narita Airport in Tokyo. I just wanted to get home, but that was the way the flight was routed. And during that layover I walked around the little airport town of Narita, and by the time I boarded the plane, three hours later, I’d decided I was going to live here. And I did.

I think most of us, when we look back on our lives, see how freakish the circumstances are that brought us to where we happen to be.

One of the nicer things about getting older is that it’s almost as if I’m in Act Four of the play of my life. As in Shakespeare, or any play, Act Four is when you suddenly begin to see the larger shape of things. And the secret logic that shapes events, which you could never see when you were in Act One and Two. So I feel at this point in my life I can better understand some of those patterns and how little they have to do with me, happily.

I guess I’m in Act Two of my play then, nearly Three. But this idea of giving in to life and letting go of the plans, the expectations I’ve built up for myself can fuel some anxiety! The idea that I’m not in control. To just trust.

Yes, absolutely. But then I think how readily I trust whichever anonymous stranger put up that Wikipedia item I read this morning, how instantly I trust whoever wrote the Lonely Planet guide to Burma that I’m going to follow next month. And quite possibly if I met those people in person, I would never begin to trust their judgements. But somehow they have an authority because they’re in print or they’re on screen. And so if they can inspire our trust, life certainly should! Part of the whole cycle of trust is, as you said, working one’s way through the anxiety. One has to make wrong decisions and do things the wrong way before one gradually begins to see what might be the better way. So I think it’s the nature of Act One or Two to be anxious, to make those plans. And then in time to see those plans upended and realise that it wasn’t so terrible after all.

[Laughs]. Something I’ve been thinking about lately is the idea that we can write the stories of our lives. That our identities are essentially the stories we tell about ourselves. And even if we’re not that person yet, we can eventually live in to these stories we’re telling. It’s in contrast to what you’re saying, I guess, it suggests we do have some control!

Hmm. Well I’ll say two things. The first is that I love the idea you just expressed. I was reading William James last week, and he gave the perfect description of the society around me here in Japan. He said: “Act as if you have faith, and that is faith. Pretend to be cheerful and that’s all the cheerfulness you need.” As you probably know, here in Japan, people are very good at putting on a public face of brightness and optimism and perkiness. And I think that actually does make the reality. They turn into the people they’re pretending or aspiring to be, and the result is certainly much better than acting the part of being morose and pessimistic. So I agree that we can prompt ourselves in the right direction.

On the other hand, when you were talking about writing our lives, I was thinking how writing is best when you’re not consciously doing it. I don’t want to sound too mysterious about this.

Things are coming out of you that you didn’t know you had inside you. And those tend to be the best things. In other words, you’re tapping into some collective mind that’s much larger and more spacious than your own. It’s the equivalent of being “in the zone,” as athletes and musicians call it. So I think that probably applies to the lives and the identities that we “script” in your terms. Little Pico thinks he’s writing this story for his life. But ideally he so forgets himself that he opens himself up to much larger things that have a mind and a way of their own. I think we’re much more scripted really than scripting.

What would eight-year-old Pico have to say about 58-year-old Pico? Would he be surprised by who he became?

Eight-year-old Pico? Well, the people who’ve known me since eight, such as my mother, would say I’m pretty much the same person! When I show my wife pictures of me, aged eight, she says, “Oh my gosh you haven’t changed a bit!” Besides losing hair and showing signs of old age!

So I love the autumn in Japan, I always try to be here in this season in November, because everything is changing and yet it’s always the same, deep down. The trees are turning colour, the leaves are coming down, we’re feeling the cycle of the air moving into the winter and coldness and dark. And yet at some level every autumn is the same. So it’s a lesson in changelessness and change. Everything is in motion and yet it’s playing out a cycle that’s age-old. I think it’s probably the same with our lives. Every day I feel like I’m doing something and making a new discovery and moving on, whatever that means. But really those are changes on the surface, and there haven’t been that many changes at the core.

To go back to what we were saying before about trusting the world, I think that it is mostly a matter of listening. We’re getting prompts all the time. I don’t mean this in any supernatural way. But I do mean that we can learn to listen to our intuitions, to the better part of ourselves. Let’s say I arrive in Burma tomorrow and a stranger comes up to me and says, “I can show you the streets of Mandalay.” Instantly two things arise in me. One is a sense of excitement, adventure, I should take this leap, that’s what I’ve come to Burma for. Another is, He may be a conman, I should be on my guard.

Do you think you’re getting better at listening to the wiser voice?

Probably not, no! [Laughs]. But I’m getting better at asking, “Why won’t you listen to it?”

[Laughs]. So I want to talk about your work as a travel writer. You’ve had the great privilege of immersing yourself in all these different cultures. And one of the beautiful reflections you have is that we travel not to move around, but to be moved. When did that realisation come to you?

I was very lucky because I travelled a lot as a small child. My parents moved from England to California when I was seven and I started going to school in England and commuting back and forth from the age of nine.

Travel became the way I lived, my mobile home. But more importantly it imparted early on a sense of home as something inward. I knew that I didn’t fully live in England or California, and certainly didn’t live at all in India, which is where my ancestry is from. My home would be a collage, and a shifting collage, made up of those and many other places. So I’m glad now that I didn’t ever have the craving for a physical or geographical home. I always felt that home was something portable I carried with me. When I was making those commutes in the 1960s it seemed like an unusual thing to do, I was the only Indian kid in my school in England. Now most of the kids in that school probably look like me, one way or another, have many homes and think of their home as a mosaic or a work in progress. That’s a nice development over the course of my lifetime: that for more and more people, home has become something inward. At the age of 58, I’ve never owned a piece of property. I rent this tiny two-room apartment I share with my wife and formerly our two kids. And when I get back to California, I stay in my mother’s house. The notion of actually occupying a house and calling it my own has never called to me.

You know, in none of what you write, or even what you’re saying now, I’ve never felt like you’re advocating a particular way of living. There’s always something to take from your writing, but I’ve never felt like you’re recommending people to live like you, with this sort of transient sense of place.

No. I’m really happy you observed that. Whatever I write about, I’m not recommending for anyone other than myself. It’s completely descriptive rather than prescriptive. I write in the hope that a few eccentrics may encounter my words and it may spark them towards their own vision. But I do think we’re all in flight from complacency. We don’t want to think we know it all. Foreignness and being in a very foreign country are useful in that sense. And I think more and more of us, and this was the subject of my last book, are suffering from the sense of feeling out of breath and there aren’t enough hours in the day.

Yeah. I hear you!

And in that sense, though I’m not recommending anything, I may be voicing a universal longing for enough space to breathe and put things in perspective. This is the reason I moved to Japan, so I would have more hours in the day. Fewer distractions and therefore a clearer sense of what I really care about. I think everybody does it in his or her own way. And each way is as good as any other.

Right. I was telling a friend last night about your work, the importance of making space to go inward. And I felt her becoming really uncomfortable. She said, “Well I can’t.” She’s 30. She said, “I’m working towards a house with my partner, I’m doing my MBA. This sounds like a journey for the privileged.” I don’t think what you’re talking about is for the privileged, but what would you say to that? I mean, I get it: Western society, capitalist society, expects so much from us. And the idea of slowing down is challenging.

Yes, that’s the problem. More and more we’re challenged and unsettled by it in part because I think we’re more and more addicted to our busyness. Our bosses expect us to be online permanently. And we feel that we’re being delinquent if we’re not constantly receiving the latest Facebook updates or CNN updates, knowing what’s up in the world.

Either we turn ourselves into machines, whereby we take in lots and lots of data but we’ve relinquished our humanity—or we just accept that the world is moving too quickly for us to keep up with every development, and we need to take a break. So I would say to your friend that if she’s thinking about the life and the home she wants to make with her partner, the best way is to take an hour off every couple of days. Take a walk around the street or along the beach. That is how she’s going to come up with the best idea of what that house and life should be. When we’re running around it’s really hard to see things clearly, especially the things that really matter to us. And it’s only by separating ourselves from this torrent that it comes into focus. I was thinking just last week that so long as you’re looking at the next appointment or the last email or the next text you want to send, there’s no way you can see your ultimate goal. Humans are not able to look at two things at the same time. Most of the day we need to think about what’s immediately before us: the baby that’s crying, the boss that’s calling us, the fun that we want to have this evening. But we don’t want to be slaves to the moment or we find 40 years have passed and we’re not in the place where we hoped we would be.

.jpg)

When you were saying before taking an hour out to go for a walk to have better thoughts, I’ve also come to realise that I can’t actually expect that from my walk, right? ‘Cause I might think, Alright, I’m going to put this one hour walk into my day now so that I will have the great thought for my work, but the great thought doesn’t come because I’m expecting it to come!

Such a good point. Expectations always defeat themselves. And if you go on retreat and say, “I’m going to come back with the answers to my life,” you probably won’t. Or if you go to Tibet and say “I’m going to find happiness and enlightenment,” you’ve all but ensured you won’t. So what you said is really wise in reminding us that we don’t want to be too focused on results.

I also note that when you’re sitting still or taking a walk or taking a break, often worries, anxieties and terrors come up. But I think that’s not a bad thing because it’s better they come up than they keep mouldering inside you or operating inside you without your knowing it. And it’s better that you can confront them in a relatively healthy context, than suddenly when the last-minute crisis comes! Part of my interest in having a little space to collect oneself has to do with that long-term reality that whoever you are, life’s going to throw up its share of crises at you. And how you deal with those crises will be in direct proportion to what your inner resources are. It’s like if suddenly somebody knocks on my door saying, “I want 300,000 dollars.” Well I can’t give it to him because I don’t have that in my bank account. When life does the equivalent and says, “This person you love is dead,” the only place I can go is inward. And if my inner bank account is empty, what am I going to do?

So true. Something that struck me reflecting on your work is that this inner journey is a very solo act, right? We’re doing it on our own. And it’s beautiful, it’s very healing for us as individuals. But I wonder what kind of global healing this solo act can have, if any.

When I first moved to Japan I came to stay in a monastery and I met a Zen teacher. And he said, “The point of our meditation, solitude, is not the moving away from the world. It’s what we bring back to the world at the end of it.” And to me it’s just like taking medicine. I find that when I’m racing around and the world is too much for me, I’m frazzled and distracted and I’m not really giving much to the people around me at all. Somebody comes up and offers a heartfelt question. I say, “I’m sorry, I have to race off.” No help to them. No help to anyone.

So actually taking time out is not just doing ourselves a favour, but doing a favour to everybody around us, too. I try to go on retreat to a monastery every season. And every time I do that, as I’m driving up, I feel so guilty to be leaving my mother or my wife behind and to be putting my email on automatic response and to be missing out a friend’s birthday party. But as soon as I get there, within 10 minutes, I realise it’s only by being there that I have anything fresh to share with my wife, my mother and my friends.

What do you practise in the monastery?

Just reading and writing. It’s a Catholic monastery and I’m not a Christian. But I think silence has been my greatest teacher. And my sense is wherever you are, and whatever your religious orientation or lack of it, just to go to silence—whether it’s by taking a walk or going into a retreat house—is like going into a hospital for the soul. You come back refreshed. It’s the best travel experience I can think of.

And these are just really accessible, practical daily things, right? As you were speaking there I realised that I put experiences like going for a walk into nature or meditating on a pedestal, I mean we see them as “spiritual” activities, “something special.” But I think that very thinking doesn’t do us any good.

Exactly. Keeps them at a distance. I think it’s as simple as when I’m driving around California, I love listening to the radio. And every now and then I’ll turn it off. And suddenly I realise, Oh, I’ve got a little holiday! Twenty minutes just to let my mind wander. Or when I’m at the health club, if I’m walking the treadmill, I turn the TV off. Suddenly, nothing to do! And that’s when amazing things will come to me. Or waiting in line in the bank. You could be fretting at the fact you’re waiting in line or you could say, “I’ve been given the chance to spend five minutes doing nothing, which doesn’t come very often!”

[Laughs]. So do you ever get anxious, Pico?

Yes I get anxious, as everybody does. But I think, cumulatively, the more time you can breathe, the less anxious you’ll become. And the more concerned about the world you’ll become, the less anxious you’ll be. The concern won’t be a kind of fretful useless neurotic energy, but a more purposeful, constructive one. That’s the hope at least.

The other double standard I was thinking about recently is that more and more of my friends are very, very particular about where they eat. They would never dream of going to McDonald’s. But after having a truly healthy and organic meal, they’ll go home and access some website with the latest Hollywood gossip and stuff junk food in their mind. And again when I see that tendency in myself I realise, This is really short-sighted, I’m taking such pains with what I put inside my mouth, and so few pains about what I’m putting inside my mind.

Yeah, it makes me think, you know when you can see your better self? It’s right there in front of you! You know the things you should do to rise out of a slump. Read a book instead of mindlessly scroll the internet. Cook instead of get takeaway. You know the better option and yet for some reason, the weight of the day or whatever, you can’t! And yet you know that if you do it, you’re going to be much happier, you’re going to feel much better about yourself, you’re going to get much more clarity. But there is a tendency, for me personally, to choose not to.

So, so true. We fail that test every day. I certainly do. We can’t expect ourselves to succeed 100 percent of the time. The key, for me at least, is remembering that you’ll actually be happier if you do that particular thing. Feel better about myself, to use the other phrase you used.

Or if we’re enjoying an intimate moment with somebody we care for. Happiness is absorption. It’s the opposite of racing to do a hundred things on the hour, running from distraction to distraction. So when I suggest to myself, “You might be happier taking a break,” I’m really trying to remind myself that my deepest happiness lies not in scrolling through the internet, but maybe just putting on some music. Or engaging someone in a deep and rich conversation. It takes—as you said perfectly—some impetus sometimes to do it. But in the end it’s going to make me a lot happier.

You’ve also worked to remove a lot of those distractions from your life. You don’t have a TV or a car and you’ve really been conscious of taking things away from you that could inhibit the absorption.

As much as I can. Because I think all those things open up space in the day. When I left New York City I thought, I’m giving up financial security and excitement and many other things that I was enjoying before. But what I’m gaining is time and freedom. What I’m gaining is a day that lasts for 24,000 hours, it sometimes seems. If the car was here, I’d be tempted to be driving around all over the place. If the TV was around I’d be tempted to watch things. And distract myself, perhaps, from clarity and happiness. The problem is never our machines, but our inability to make the wisest use of them.

When you made that decision at 29 to go from fast-paced Manhattan life to slow things down in Japan, did it ever feel like you were escaping?

No, I must say it never did. I was lucky because I’d done well enough in my job that I could afford to leave it without any regrets. That is a rare privilege. I feel you can’t turn your back on the world until you’ve made your peace with it and come to terms with it. And at 29 I didn’t have a wife or kids, so it was easy to take a leap into the dark. At the time, it felt like the next interesting adventure, to explore solitude and simplicity in a very foreign place. I have friends who left the United States to live in Japan because they disliked the United States or felt there were no opportunities for them. Came to Japan, built good lives here, but I think there’s still some restlessness because they never accomplished what they wanted to in the United States. There’s unfinished business with them at home. And so that is a different situation I think.

They knew they didn’t want to be in Australia or England, but they didn’t know that they particularly wanted to be in Burma or Bali. And I felt, Well, I don’t want

to get in that state where I’m defining myself by my dislikes or by the places I want to leave behind. I want to be defining myself by what I’m moving towards. There’s a big difference between flight and pilgrimage. And I think the pilgrim’s way is much happier than the fugitive’s [laughs].

[Laughs]. It makes me think of a quote which is related to what we were talking about before. “The pilgrim is all acceptance, no expectation, whereas the tourist is all expectation, no acceptance.” I really love that!

Yes! I read a great quote from Henry Miller the other day, he said— also a variation on what we’ve been talking about—“Understanding is not a piercing of the mystery but an acceptance of it.” But to go back to your previous question, which is such an interesting one, about escape. I think all of us are escape artists in certain ways. There are certain things we’re always fleeing and trying to escape. And I think those are the points of insecurity or uncertainty or vulnerability in us. I mean there are certain things I run away from and I realise those are things I haven’t sorted out in my life. But New York City and my life in the US was not one of those.

I guess I ask about that because I’m 29 now and I’m trying to build more space for simplicity in my life. But the idea of leaving things here in Melbourne to pursue that would feel like escaping. Perhaps it’s what you’re saying, that I have unresolved business here.

I think entirely that. And that’s a good reason not to leave. I mean, I don’t see having space in one’s life as an end in itself. There’s a certain point in everyone’s life when you feel you’re out of balance. And you’re getting too much stimulation and you need calm. Or, in some people’s case, too much calm and you need stimulation. One just has to be attentive to oneself and see what the moment requires. It sounds like your moment requires being exactly where you are. Maybe your friend you were talking to last night, the same. Which is why I would not prescribe anything.

So I’ve got written in my notes “heart versus head.” And we might be covering old ground, but I still want to ask. This idea of the heart is something we talk about often as if it is actually something— not in an abstract or conceptual way, but something that is very real. And yet I don’t actually know what it is. I know we’re talking about coming from a place of compassion and empathy, but I’m wondering what meaning it has for you: to act from the heart?

I would say that even if we don’t know what it is, we know what it isn’t. And what it isn’t is the mind. The mind, in the smallest sense of the word, is all about making distinctions and comparisons and judgements: “I don’t like this” or “This is better than that.” And there’s something else in us that’s much more spacious and expansive. For example, if I get a negative review, my mind may start chafing and coming up with its own arguments, as if in a law court, against the poor reviewer. But my heart, my spirit will see a much broader picture. I think the mind is the repository of the small “I” or the little ego in us that’s chattering and wants to protect our own identity, our position in the world. And sees the rest of the world as an enemy, or something to be figured out. Whereas that other part in us is much more about dissolving distinctions.

Yeah! I just realised that it’s probably my mind wanting me to know what the heart is. But the heart would say it doesn’t matter!

Wonderful! I love that. Yes, it goes back to what I was saying at the start: that I only trust the things I can’t explain. So the mind is looking for differences when the heart is looking for convergences, perhaps.

I also wanted to know, it’s a big question, but what do you think is the greatest challenge we’re facing as a global community now?

I think the 21st century is the century of the “Other.” So whether you’re in Sydney or Toronto or London, you’re now surrounded by people from radically different backgrounds and cultures from your own. And how you deal with them is going to affect your life and the life of the community. That’s something the age of movement has brought to our doorsteps.

And that poses a challenge to England and to each of the students as to how they’re going to hold onto their sense of identity and community when they’re surrounded by people with very different beliefs. That’s a useful threshold for the world to be crossing. Culturally we know that so far this cultural mingling has been almost entirely beneficial to the world. The food you have in Australia is much better than before. Not just because there are 160 different nationalities represented, but also because of the mixtures between them.

But politically it clearly poses a challenge. Some people are so unsettled by it that they’re falling back into greater tribalism than ever on both sides of the divide. Every day, when we pick up the newspaper, we’re reading about variations on this theme. And I think that’s our main challenge right now.

To connect with people on a level that is open.

Yes, and simply to accept that this is the way things are and will be. That our grandparents lived in a world where they could go through most of their lives seeing people who looked and thought very much like themselves. We can’t. What are we going to do with it? It doesn’tmean necessarily that we have to throw our arms around it. Though I happen to do that. But it does mean we have to accept that you’re in a world more complex, and therefore a lot richer, than the one we used to have, and it raises questions you can’t run away from.

I’ve been going to places like Alice Springs recently. And when I’m in Alice Springs I check into the hotel, all the guys there are from Bombay. I go to eat in a little town, everyone there seems to be from Singapore or the Philippines or elsewhere. So for the typical family from Alice Springs whose ancestors have lived for maybe 200 years in a way that hasn’t changed much, they’re going to have to wake up to the fact that this is a new reality. And at least make their peace with these Indians and Singaporeans and others who are in their midst. They don’t have to love them, but it’s certainly not going to help if they hate them.

You don’t think that we should be taking that one step further than just accepting, to actually connect, try finding the common humanity?

Well that’s the ideal. But that may be asking more than many people are prepared to give. The first step is just saying: “This is the reality. You can’t pretend things are the way they were before and you can’t try to take them back to where they were in previous generations, because airplanes and technology have made that impossible. Wherever you are, you’re going to be in a mixed community now.” And so make the most of it, I would say. It’s not a threat, it’s our new reality.

So Pico, you talked about being in the Fourth Act of your life. And I wonder, going into the Fifth Act, do you have any hopes, ideas for how it could play out?

Hmmm. I mean the beauty of it, as with any stage of life, is that it’s completely unknown.

That’s right! [Laughs]. It’s a flawed question given everything we’ve been talking about!

No, but as I survey this field I know nothing about, I figure two things are going to happen. Because they seem to happen to most people. Much more physical infirmity, in myself and in the people I care for. Many of the things I could do I won’t be able to do. But also much more mellowness, perhaps. People tell me that as they hit their sixties and seventies they get much more accepting of the world, less fretful. I think some studies would say people are happier than ever then—even in the midst of infirmity. So that’s rather hopeful. It speaks to what we were saying about suffering and how one deals with it, in terms of gathering inner resources. When one’s in one’s sixties or seventies, the hope is that one will have gathered quite a lot of inner resources so that even if there are more physical infirmities, there’s a stronger mind to deal with them. And a much more seasoned being to work with them, who may not be shocked by their presence as one would be when one’s 18.

I’m a great fan of the writer Graham Greene, and it’s wonderful to see that he, like Shakespeare, went through this very turbulent time in his forties, as I think many people do, raging against the universe. Shocked that things weren’t the way they seemed to be.

And of course, the plays Shakespeare wrote at the end of his life, which in his case was in his fifties, took on suffering and betrayal and seeming death and worked their way through the darkness to come out at the other end into a springtime that feels earned. So that’s the nicest thing to look forward to if any of it is coming our way. That the winter’s tale will end in cherry blossoms.

Will you keep moving do you think?

Yes, it’s the nature of my life and my temperament, probably, to move a lot. So I always will. But movement in itself is less exciting to me than it was. And I’ve been lucky to see many of the countries I’ve most wanted to see. So I think stillness is the big adventure for me now. And sitting still at my desk is what I would most like to do. Because a lot of the explorations I would still like to conduct would take place there. So my hope is that I’ll get some time to do that in the midst of the movement that’s necessary.

.jpg)

Syndicated with permission from Dumbo Feather, a magazine about extraordinary people and there mission is to inspire a community of creative, courageous and conscious individuals. Mele-Ane Havea comes to Dumbo Feather with a varied background, from corporate law to community and human rights law, with an Oxford MBA thrown in for good measure. At business school and the Skoll Centre for Social entrepreneurship, Mele-Ane became enamoured by the idea of social and responsible business, and the power of story-telling.

Nathan enjoys getting elbow-deep in sentences, pressing and pricking them like a Chinese doctor until the blood is flowing just right. He hails from Western Australia, where he first experienced the joy of putting together a magazine, and now indulges his love of thoughtful, life-giving storytelling by bringing Dumbo Feather to life once a quarter.

On May 11, 2018 Patrick Watters wrote:

Much beautiful truth here. We must each find our own way with intention. We have a story within a greater story. }:- ❤️

1 reply: Elaine | Post Your Reply