How Language Enabled Innovation and Evolution

Why remix culture and collaborative creativity are an evolutionary advantage.

Much has been said about what makes us human and what it means to be human. Language, which we’ve previously seen co-evolved with music to separate us from our primal ancestors, is not only one of the defining differentiators of our species, but also a key to our evolutionary success, responsible for the hallmarks of humanity, from art to technology to morality. So argues evolutionary biologist Mark Pagel in Wired for Culture: Origins of the Human Social Mind — a fascinating new addition to these 5 essential books on language, tracing 80,000 years of evolutionary history to explore how and why we developed a mind hard-wired for culture.

Much has been said about what makes us human and what it means to be human. Language, which we’ve previously seen co-evolved with music to separate us from our primal ancestors, is not only one of the defining differentiators of our species, but also a key to our evolutionary success, responsible for the hallmarks of humanity, from art to technology to morality. So argues evolutionary biologist Mark Pagel in Wired for Culture: Origins of the Human Social Mind — a fascinating new addition to these 5 essential books on language, tracing 80,000 years of evolutionary history to explore how and why we developed a mind hard-wired for culture.

Our cultural inheritance is something we take for granted today, but its invention forever altered the course of evolution and our world. This is because knowledge could accumulate as good ideas were retained, combined, and improved upon, and others were discarded. And, being able to jump from mind to mind granted the elements of culture a pace of change that stood in relation to genetical evolution something like an animal’s behavior does to the more leisurely movement of a plant.

[…]

Having culture means we are the only species that acquires the rules of its daily living from the accumulated knowledge of our ancestors rather than from the genes they pass to us. Our cultures and not our genes supply the solutions we use to survive and prosper in the society of our birth; they provide the instructions for what we eat, how we live, the gods we believe in, the tools we make and use, the language we speak, the people we cooperate with and marry, and whom we fight or even kill in a war.”

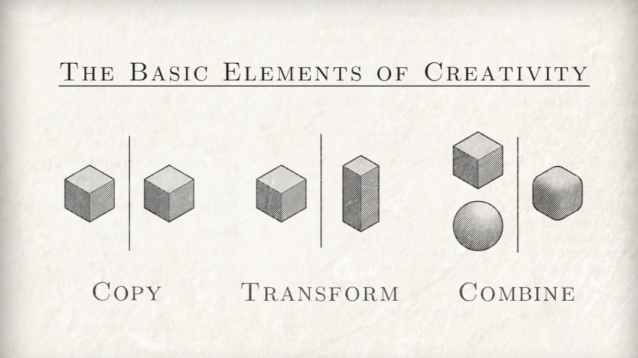

But how did “culture” develop, exactly? Language, says Pagel, was instrumental in enabling social learning — our ability to acquire evolutionarily beneficial new behaviors by watching and imitating others, which in turn accelerated our species on a trajectory of what anthropologists call “cumulative cultural evolution,” a bustling of ideas successively building and improving on others. (How’s that for bio-anthropological evidence that everything is indeed a remix?) It enabled what Pagel calls “visual theft” — the practice of stealing the best ideas of others without having to invest the energy and time they did in developing those.

It might seem, then, that protecting our ideas would have been the best evolutionary strategy. Yet that’s not what happened — instead, we embraced this “theft,” a cornerstone of remix culture, and propelled ourselves into a collaboratively crafted future of exponential innovation. Pagel explains:

Social learning is really visual theft, and in a species that has it, it would become positively advantageous for you to hide your best ideas from others, lest they steal them. This not only would bring cumulative cultural adaptation to a halt, but our societies might have collapsed as we strained under the weight of suspicion and rancor.

So, beginning about 200,000 years ago, our fledgling species, newly equipped with the capacity for social learning had to confront two options for managing the conflicts of interest social learning would bring. One is that these new human societies could have fragmented into small family groups so that the benefits of any knowledge would flow only to one’s relatives. Had we adopted this solution we might still be living like the Neanderthals, and the world might not be so different from the way it was 40,000 years ago, when our species first entered Europe. This is because these smaller family groups would have produced fewer ideas to copy and they would have been more vulnerable to chance and bad luck.

The other option was for our species to acquire a system of cooperation that could make our knowledge available to other members of our tribe or society even though they might be people we are not closely related to — in short, to work out the rules that made it possible for us to share goods and ideas cooperatively. Taking this option would mean that a vastly greater fund of accumulated wisdom and talent would become available than any one individual or even family could ever hope to produce. That is the option we followed, and our cultural survival vehicles that we traveled around the the world in were the result.”

“Steal like an artist” might then become “Steal like an early Homo sapiens,” and, as Pagel suggests, it is precisely this “theft” that enabled the origination of art itself.

Sample Wired for Culture with Pagel’s excellent talk from TEDGlobal 2011:

This article is reprinted with permission from Maria Popova. She is a cultural curator and curious mind at large, who also writes for Wired UK, The Atlantic and Design Observer, and is the founder and editor in chief of Brain Pickings. More from Maria on DailyGood: 7 Must-Read Books on Education 7 Ways to Have More by Owning Less Where Children Sleep: A Poignant Photo Series The Neuropsychology of "Don't Worry, Be Happy"

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On Mar 11, 2012 Noor A.F wrote:

wonderful ! the theft helps the thieves at least the thieves would try to invent the same things or even higher arts.

If a singer just sang unknown rhyme of songs then the other singer has top that and sell better than.

such this shows the theft doesn't only encourage the watcher but also inspired their abilities.

So it is better to look or search something that excels the theft or comes near to what is stolen.

We are just africans here and we try to reach where the westerners passed 19th century.

Just struggling

1 reply: Ricky | Post Your Reply

On Mar 11, 2012 Hsn Bhatta wrote:

it is a sad fact that language historically has ruined civilisations and divided human beings.an universal language with commanality as of now would make language a unifier. who bells the cat""

On Mar 13, 2012 wes wrote:

The Yellow patterned background under the text is annoying and almost unreadble

Post Your Reply