How Do We Wake Up?: A Conversation with Mark Dubois

.jpg) When I first began hearing about Mark Dubois, his name was mentioned with a note of awe. “You’ve got to meet him, Richard!” People like giving me suggestions and I’m grateful for them; this one, however, had a different energy about it. But then nothing further happened. It wasn’t until two years later that I met Dubois at a ServiceSpace gathering. One doesn’t forget meeting Mark. First, he’s taller than almost anyone you’ve ever met. And second, you receive the longest hug from a stranger you’ll ever run into. It makes an impression. The man is a force, an embodiment of a special dimension of love that manifests in an irrepressibly physical way: Wake up! Life is amazing! We’re all in this great adventure together! Look at the miracles all around us!

When I first began hearing about Mark Dubois, his name was mentioned with a note of awe. “You’ve got to meet him, Richard!” People like giving me suggestions and I’m grateful for them; this one, however, had a different energy about it. But then nothing further happened. It wasn’t until two years later that I met Dubois at a ServiceSpace gathering. One doesn’t forget meeting Mark. First, he’s taller than almost anyone you’ve ever met. And second, you receive the longest hug from a stranger you’ll ever run into. It makes an impression. The man is a force, an embodiment of a special dimension of love that manifests in an irrepressibly physical way: Wake up! Life is amazing! We’re all in this great adventure together! Look at the miracles all around us!

I didn’t quite know what to make of this startling man, and when I proposed an interview, I didn’t know what to expect. It turns out I knew little of this man’s work, of its extent, or of the depth of his experience and vision. Whatever the forces were that led to our conversation one afternoon in Corte Madera, I bow to them in gratitude. —R. Whittaker

works: I’ve seen bumper stickers saying something like, “Get God out of the Environmental Movement.” It seems some people don’t want anything spiritual being part of it. I was wondering if you have any thoughts about that.

Mark DuBois: You know, using the word God and spirituality opens a minefield. But when I came to the river, it touched me in a way I’d never been touched before. It’s only in recent years that I’ve started feeling there’s a sacred connection.

I was having a discussion with David Korten—he wrote When Corporations Rule World—and when David Korten started using the word sacred… Anyway, it’s 50 years since I fell in love with the river.

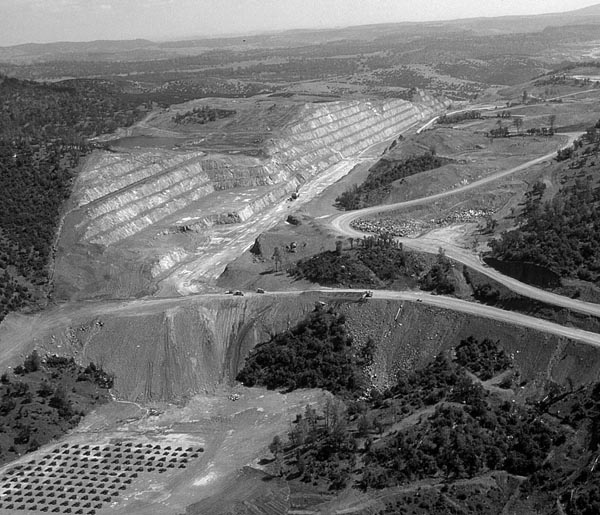

Last year I was camped in the holocaust zone caused by the reservoir [New Melones Reservoir] along the river that tutored me, the Stanislaus. I was asking myself, “Why did I come here?” There were just skeletal trees and millions of years of topsoil had been sloughed off because of the reservoir. My heart was broken everywhere I looked. And in the middle of the sixth day—I was only as far as what used to be beautiful Rose Creek with its pools—as I woke from a nap, this subtle voice said, “It doesn’t matter if you sound like a complete loon talking about what this place tried to teach you 50 years ago, you’ve got to start speaking.”

So back to your question about God. I do know there’s a miracle going on. We can tamp that down and be asleep, but I sense there’s this intuitive knowing that something is wanting to be birthed through each of us. I think Einstein said, “There are two ways to look at the universe: nothing is a miracle or everything is a miracle.”

I remember after a couple years of commercial river-running, I took inner city kids down the river and the river brought something out of their souls and being. Somehow the river and the canyon cleansed our souls. That’s when I started realizing people in the cities don’t smile like they do when their whole being is cleansed on the river.

works: What are some of the roots of your connections with nature?

Mark: My dad’s parents divorced when he was young. He went to seven different junior high schools. We used to visit my great-aunt in the hills and beautiful woods overlooking Pope Valley. Sometimes we’d go camping at Lake Tahoe. At some point, for $200, they ended up getting a mining claim up in Trinity County along the South Fork Trinity. We had to hike in a mile to get to our old, one-room, tin cabin, and we went up there five or six times a year. So all of those places rooted me. My mom’s family had retired in Grass Valley and Nevada City, and we used to go up there and visit them. It was an old mining and hunting family. Trinity was really the most anchoring, and then eventually the Stanislaus.

works: Tell me some of your early memories.

Mark: I’ve got memories of being in nature—the little ponds, the creeks, the arrowheads. In retrospect, I realize my dad knew a lot of the plants. He knew especially the agricultural plants, but also some of the wild, native plants. So when I got on the river, I had a head start on most of the new guys, and I was like a sponge learning these plants who are now my friends.

works: And you’d have been about how old then?

Mark: Sixteen, because I could drive. I was an awkward, shy, gangly kid. Iit was so painful for me to be around people, but discovering caves, wow, here were places to explore! Initially, the dry, hot foothills were unattractive. I was used to evergreen, conifer forests. The dry foothills were ugly, but at least there were caves there. Over the years I fell in love with those foothills and all these plants that had learned to survive in the drought for six months every year.

works: You’re really tall [6’ 8”], so you were probably really tall as a kid, right?

Mark: I was always tall and gangly. My dad says that when I was on the ninth grade basketball team I played a total of five minutes the whole season.

works: That must have been painful.

Mark: Well, I didn’t remember this. I probably blocked it out. At that same age, there was a little Hispanic kid and we got in a tussle; he outjumped me. I mean, I just had no coordination at all. So that made me even more shy. But in the caves I could go places where no one else could. So I thrived with that, and then there was the river.

works: No problems with claustrophobia?

Mark: One of the first wild caves I went into didn’t go very far. Then I saw this little hole. So I squeezed through it into this tiny room. Then I turned around and tried to get back out. But I was breathing so hard

I got stuck. Then claustrophobia hit me. But after about a minute I’m thinking, “Wait a second. I got in here. So do I breathe in or out to get smaller?” And I got out. After that I never got claustrophobia again.

works: That’s kind of incredible. So you mentioned the South Fork of the Trinity River…

Mark: The South Fork Trinity was where we’d go, probably from when I was ten on; it was a sanctuary for my family. My parents were having more and more tension. But at Trinity, this one-room cabin in a magical forest was a place where there was complete harmony. My brother and I were off with our friends, running, swimming in the stream. Just 100 yards, and we were down at this incredible creek with eight-foot-deep, crystal clear pools of Northern California water, with salmon and plants and nature, and we learned in spite of ourselves. It was chop wood, carry water—a simple life.

works: I wonder if you have any thoughts about your early relationship with all that?

Mark: We lost the cabin we had, and about ten years ago, Sharon and I went up and camped there. I was just blown away with the beauty of the place. You know, from the maidenhair ferns to the Indian rhubarb, the colors and the light—I’d just taken all that magic for granted, but I know it deepened me, even if I didn’t fully see it.

It’s like with the Stanislaus. I feel like I went down that river 100 times before I started to see it. When I hiked the river later, it was, “Oh, this is where that creek enters!” The rapids had blinded me from seeing it! I mean, earlier we kept seeing all that, but the excitement of the water made me stop looking—and nature’s subtleness changed me even when I wasn’t aware of it. In retrospect, I feel sort of like an insensitive oaf who got to play in the fields of the Lord and had no idea where I was, except it made all of us smile.

This beautiful little canyon touched the hearts of so many people. As I said, for my dad it was like a sanctuary. And with my mom, who had her Irish temper, there was just calmness up there.

When our son was growing up and when something would happen, like an accident inside, I’d take him out the door and he’d stop crying. So even if we don’t have language or recognition of it, my experience is that nature works through us..jpg)

works: Earlier you said you were leading river-rafting trips. You were actually taking kids down the river?

Mark: Yes. During that first caving year (we’d gone to the National Speleological Society Mother Lode Grotto, which I eventually became president of), as we came out of this cave called Gold Tooth, we looked way down and someone said, “They’re building a dam on that river.” But I’d grown up with my parents going to reservoirs, so that was “progress.”

works: Right.

Mark: Then a couple of weeks later my brother said, “Remember that road we drove down? It’s the same road where we put the rafts in further down with our friend, Ron Coldwell.”

Well, little did I know that that river, and that road, would be such an ingrained part of my life. During high school, because I was into archeology, I helped organize some archeologists going down there because we knew the dam was coming.

By 1970, my brother had been a commercial river guide for a couple of years. So I also became a commercial river guide on weekends and fell even more deeply in love.

The next year, when all my friends went off to exotic rivers, I stayed as area manager. By then I was doing it full-time and was on the water five and six days a week. I was learning and sharing about the plants and animals, and also about the stars! I was also teaching archeology and historical mining. Each time I went hiking, I made new discoveries including Native American sites. Again, my love affair deepened.

works: Had you gone to college to study archeology?

Mark: That’s what interested me.

works: Let’s go back for a minute. In high school you became the head of some things?

Mark: The American Field Service, a student chapter and then Key Club, Kiwanis.

works: So somehow you made a transition from being so shy and awkward and started putting yourself out there, it sounds like.

Mark: My parents sort of coerced me to going to the AFS meeting. I still was painfully shy, but if the club needed something done, I could do things. And because I did things, they pushed me up to the front. I learned a lot. I don’t remember how I got involved in the Key Club. But it was a collection of misfits.

I’ll share one story that’s interesting for me. You heard how my junior high basketball skills were. Right? But now we were playing volleyball indoors. As usual I was on the team with the misfits. Our coach was a great jock and just a big, sweet guy. And because there was an odd number of teams, every year he would play single-handedly against each team. He’d never lost.

He taught us to play the zone and I remember directing my teammates, “Remember you were over there? Remember to stay there!” And we played as a team and ended up beating him. He denied it, because the uncoordinated outcasts had beaten him.

So it was shocking to me, as a good Catholic, to have a teacher lie. But it was a story I could tell again with the misfits. And the Key Club was sort of that same way, with kids who didn’t fit anywhere. But we all cared, and it was a service club, and we could serve.

works: That’s great.

Mark: My mom kept us close to the apron strings and growing up, friends were usually at our house. Soon we had AFS meetings at our house and it became the place to be, because my mom made a cake a day and both my parents connected with these kids. Then, because of me, my parents got involved in the parent chapter. My mom, born and raised in Sacramento, had never been out of California until she met my dad and they got married in Reno. And to practice my fledgling French, I would only answer her in French, and before long she started bringing all the exchange students together from around town. So we got to know all of these international kids.

I guess that was a couple of years before I became a river guide. I took a break from college and went traveling to Europe for six months. I went as far east as Iran. I visited my friends, these exchange students. That trip really made me understand that everyone else is shy, too, and if you’re ready to talk, most everyone’s ready to talk. No one wants to do it first.

works: That’s a big discovery, isn’t it?

Mark: It was a big discovery. When I came back, I learned to be able to ask questions, and I learned how to speak and listen.

works: That’s a great story.

Mark: So those two commercial years on the river were great. We had amazing trips, and the next year, I could go anywhere I wanted: the Grand Canyon, Middle Fork Salmon..jpg)

works: What do you mean you could go anywhere?

Mark: The company was going to send me anywhere I wanted. It turns out my friend, Fred Dennis, came up with the idea of taking inner-city kids out for free. The idea was so exciting. As much as I’d heard about all these incredible rivers, and wanted to go there, Fred’s idea hooked something deeper.

works: Tell me a little bit about that.

Mark: Well, one digression. Ron, who had been my tutor on the rivers, knew where the army surplus sales were. So, not having a boat, we go to Mare Island. Ron said, “I heard there’s going to be a sale there.”

So we drove out there and they told us, “No rafts for sale this time.”

“What do you do when the rafts are bad?”

“Oh, we dump them. In fact, I just dumped one in the dumpster.”

“Could we get it?”

“Sure.”

Then the dump truck drove off. We followed it out to the base dump and found all these rafts out there. Each one just had a knife cut—and there were pumps, flares, paddles, C-rations and C-clamps. Then we see this red pick-up coming with an MP. “What are you guys doing out here?”

We tell him the whole story and he says, “You have to see the base commander about that.”

So we went to see him. And after hearing our plans to share the river experience with inner city kids, he says, “You can’t take any rafts, but you can take ‘patching rubber.’

So we emptied the seat out of my little 1957 Volkswagon, drove out there and got three rafts, pumps and all! That “patching rubber” is what enabled us to start.

Initially, it was just Fred and Mark; then it was Fred, Ron and Mark; and then it was Fred, Ron, Mark, etc., because people joined us.

Fred had the idea about taking out inner city kids in the fall of ‘71, before I left to explore a river in Guatemala. On my return I called Sacramento County Girls School, Boys Ranch, the Saint Patrick’s Children’s Home, Sacramento Free School, and lined up outings for more than half a summer. We camped by the river. We didn’t have money or insurance. We’d say, “Bring some food plus a little extra for the nights when we’re not on the water, and a little money to cover gas…”

So with their institution’s food and a little gas money we had these amazing trips. It was really sweet watching these kids who had never been out in nature come alive.

At one point, a San Leandro teacher friend wanted to do cheap trips for her junior high kids, and those couple of trips actually funded things like tires or truck repair.

We saw with these kids (in-trouble or “normal” kids) that on the river they were the same. Nature is this great equalizer. It was a very moving experience watching their transformation. And eventually, we started doing five-day trips. We took these kids into caves; we took them hiking and rappelling; we taught them plants and stars; we explored Native American and mining sites and shared those histories. The five-day trips were special. We didn’t get to do many of them before life intervened, but we felt the depth of change in these youths, with five days in the wild. It was a powerful experience.

works: I’ve heard that some inner city kids who have never been in nature are scared when they get out there. Did you see that?

Mark: Yes. “What kind of wild animals are here?” And the fear about the river was that you’re going down white water and you could die. What I learned, even in those first commercial years, was that being stripped down to the same uniform—a swimsuit—we were all the same. You didn’t have a blue collar/white collar divide and fear stripped away any pretense. So it was this incredible equalizer.

The company I was with had been a non-profit. It had come out of Sierra Club, and we were all there to connect people. It was this beautiful crucible where we were learning and teaching and connecting. We made friends. It was a moving experience and just so stunning to watch how the outings changed people’s lives.

I discovered that the less I had, the more I had. One day, at the end of a trip, there was a young doctor who’d been part of it. No words were spoken, but I saw the look on his face as he hesitated jumping into his new Porsche. He knew no amount of money could buy what we had.

works: Can you sketch out some of the steps between where your story leaves off here, to the point where you began to advocate for the rivers?

Mark: Yes—from my very first caving trip and learning it was going to be dammed, to being a river guide, to writing postcards to the Resource Secretary and to the Water Resources Control Board and so on.

I remember going to a hearing of the California Water Commission. It was, “John. You want a project? Sure, we’ll give you your project.” All these men in suits were giving away California’s rivers. And only one person, Jerry Meral, got up and spoke on behalf of rivers. You could tell he left them all dumbfounded because he knew so much, and they weren’t used to being challenged like that.

Fred and I occasionally would take VIPs down the river. We had no idea who they were, but we volunteered to help. This was early river-running. And overnight river-running became extremely popular. The outfitters realized that if they didn’t start working together, others were going to crowd the river up, and it was already crowded. So they begrudgingly got together. Then, with the BLM, they worked out some guidelines. So there were a dozen companies doing this. Fred and I were the only non-commercial one, and we were there to speak for the river.

At one meeting Jerry Meral came and said, “In 1970 the Coastal Initiative was successful, so next year in ’74, we’d like to try to do a thing called an initiative for this river. And if that happens, we’ll need each of you guys to give two dollars per user-day.” Then Jerry says, “Mark. How’d you like to coordinate Sacramento for signature gathering?”

“A couple of hours a day? Sure. I’ll be glad to do that.”

Well in a river, there’s a place called a “tongue.” It’s where the river narrows and all of a sudden the glossy green, smooth water takes you to the biggest waves. Once you enter the tongue, you often can’t go back.

Saying “yes” to Jerry was entering the biggest tongue of my life. It sort of swept me away from living on the river to trying to figure out how to speak for rivers in the city. I not only coordinated Sacramento, I started coordinating busloads of people to go down to LA.

works: Something must have possessed you in order to be able to do this.

Mark: At one point, Fred, Ron and I sensed that the Stanislaus was going to be gone, so we starting thinking about finding another river. We looked at the South Fork American; it’s beautiful, but it’s all private land. That wouldn’t work. There was the Tuolumne, but the Tuolumne takes really high-tech equipment and it’s really dangerous. So we couldn’t do that. North Coast rivers are hours and hours away. And there was no limestone canyon of any note on the whole West Coast like this place on the Stanislaus. It was profound wake up to how unique the Stanislaus was.

works: At this point how many years had you been doing this?

Mark: I’d been going off and on with my friends and brother through ’67, ’68, ’69. In ’70, ’71, I did the commercial river guiding. Then in ’72, ’73 I was doing it with Fred and Ron. Then they moved on by 1974 and a bunch of other dear people grew the vision. At the same time I was sucked into the campaign.

works: So this was a big change in your life getting swept up into organizing people.

Mark: My first day of gathering signatures I was so passionate. I remember going to Florin Mall, and I was able to get 99% of the people to sign the petition.

works: That’s amazing.

Mark: Somehow, because of my shyness, I’d learned how to read people. As I got more attached, I wasn’t as successful. But those first days, I was bringing river magic to a shopping mall.

works: Which is interesting, because this must have been like a new kind of wilderness exploration for you going out into the public like that.

Mark: I’ve recently told young people who are starting to gather signatures, “I know how hard this is, but there are no classes that will teach you what you’ll learn here. Learning how to read people will serve you in everything else you do.” So, yes, you caught that.

works: Everyone is a new adventure.

Mark: And there’s no textbook. Nobody teaches you how to pay attention to other people wherever they are—and to make eye contact. Right? Connecting is not a skill being taught in school.

works: Right.

Mark: And I cared so much. My dad had forced me to take public speaking, because he was so afraid of it. The first time I gave a talk at a junior high I had to hold my knee because it was shaking so bad, and I read the words as fast as I could. But because of my love of the river, I volunteered to go out to the high school to speak. I wanted to get over my fear because I knew I had to find a way to convey the magic of the river. And Jerry Meral made it easy. He prepared us with a one-page sheet of the hardest questions like, “Why don’t we need the power?” with powerful answers like, “But this reservoir isn’t going to provide that much power.”

So all of us got this major tutorial about water politics, and since I didn’t know how to put words on why I was really doing it, his techie answers were great..jpg)

works: Can you try to say something about the real reason you were doing it?

Mark: Maybe I’ll jump to a story from years later. We’d lost one more campaign, and the brainstorming was next. It was late at night; we were doing pretty good at mourning our losses, and yet had no idea of what’s next

Early the next morning I go hiking up Wool Hollow, which is on the edge of this beautiful beach at Razorback Camp with this turquoise water cascading down the limestone cliffs. Buckeye trees were all around in bloom and grapevines stretching out; damselflies and butterflies around with water-skeeters on the water. In that moment, I just felt the life of that place. I had learned we didn’t need the power or the water, and this dam was a financial disaster. I knew I couldn’t walk away or I would be like the people in Nazi Germany who turned a blind eye to what their country was doing.

They already had huge dump trucks at work, two of them every hour. I was thinking I was going to go and take one boulder at a time, maybe with a wheelbarrow, and try to move it off. I knew it would be futile, but I knew I could probably organize two of us a day to get arrested for a month at a time. Then, if we got out of jail, we’d go back and do it again.

works: So they were dumping, meaning construction was already underway?

Mark: The New Melones Dam was now at full tilt.

works: So the dam construction had begun, and you were mourning your losses.

Mark: Yes. And we kept campaigning. At some point, I thought, okay, if they’re going to flood nine million years’ worth of evolution—the Sierra canyons started carving nine million years ago—they could flood one more critter. That thought had surfaced.

There was now congressional legislation going with Phil Burton; we were still mobilizing people and the State Water Board had said to the Army Corps of Engineers, “You haven’t demonstrated a need for the water. We’re not going to let you fill up the reservoir until you can prove there’s a demand for the water.” And the Supreme Court had ruled that states have the right to allocate their water as they deem necessary.

Yet we got word that the Army Corps of Engineers was going to violate the Supreme Court mandate and the State law and flood the canyon anyway. They wanted to test their turbines, and decided to take advantage of the big spring melt. So I realized that if

I was going to do this, this was the year I was going to do it.

My friend’s office was on Taraval Ave. in SF, so I hiked from there down to the ocean, and I walked all around San Francisco with my feet in the water most of that morning. By the time I got to our Fort Mason office, I’d resolved, “I’m going to do this.”

So I called Fred. “You’re the only one I know of who knows how to weld. Would you mind making some shackles for me?”

His response conveyed that, if I died, he’d feel guilty the rest of his life. I realized then that I couldn’t ask for help. Then I called a couple of other people who said that they would be interested in joining me. I asked, “Well, are you interested?”

“It will just be us alone? I thought there’d be 100 people.”

So no one else was interested.

A couple nights later, our research nerd comes and says, “Mark, the water’s going to be up by Monday.”

It was a sheer panic moment. I didn’t know how to do it; I didn’t want to commit suicide. I wanted them to consciously know what they would be doing. So that night

I drafted my letter to the Army Corps. The next morning, I went to the hardware store and got a length of chain. I found some directions about how to tap into bedrock and by the time I came back, my friends had typed my letter to the Army Corps.

I dropped the letter off and went by Jerry Brown’s office to drop a copy for him where, six months before, 20 people had marched up with a little wagon carrying a Toyon tree. They have red berries; they’re all over California. Do you know the Toyon?

works: I think so.

Mark: It was a week’s walk, a hundred miles. A group of twenty volunteers had taken this Toyon and planted it with 400 people protesting the dam outside the Governor’s window. So now I went to pay homage to it, the only living plant left in the lower canyon; the reservoir had drowned the rest. And when I got to this shrub, it had grown.

In that instant, I had the most powerful epiphany I’ve ever had in my life: “It didn’t matter if I was alive for five days or for 100 more years.” This experience transcended any fear I’d ever had. It was the most amazing sensation. It was the most right thing I’d ever done. If I had to speak for life with my own death, it didn’t matter.

I didn’t trust the media because every time I’d tried I always got misquoted or was too inarticulate. Long story short, a river friend, Don Briggs who was a river guide himself (his Grand Canyon photos have hung in Paris, Tokyo, the Smithsonian and New York), a few years earlier had asked, “How can I help? Oh, the river needs much more coverage.”

One of his Grand Canyon passengers had been the president of NBC, and was intrigued by the Stanislaus River campaign. He invited Don to visit on his next trip to New York City. After hearing more of the story he jotted down a list of the NBC department heads and told Don to go visit them. And Don also went to Time and Newsweek and other places and made connections. Then every couple of weeks, he called these people and gave them updates. For a year and a half, he’d gotten in because he shared the stories of tens of thousands of people who were engaged with the Stanislaus River protest.

works: Then they all wanted to cover your chaining yourself in the canyon, right?

Mark: There was coverage all over the place! I’d become a news hook. I’d become famous because of Don. And he was able to get in because of this decade-long, grass-roots struggle on behalf of this little river and its magic..jpg)

works: You did chain yourself to the rock?

Mark: Yes, to bedrock.

works: And if they let the water in, you would have drowned.

Mark: Had they continued filling, yes.

works: That’s an amazing story.

Mark: On one level, it was one of the quietest weeks of my life. For a few days, they were looking for me.

I’d never been prey before, you know, hearing the searching motorboats and helicopters. But I had this perfect little perch where I could crawl under the rock, with a beautiful blooming buckeye tree that blocked most of the view. So there was only one tiny place where they could see me. And I wasn’t broadcasting, “Here I am.” I was hiding.

works: You said it was one of the quietest weeks.

Mark: Other than a few moments of panic at being hunted. I’d taken a bunch of paperwork because I didn’t know what was going to happen and, with Friends of the River, I was always behind. It was fascinating to watch how quick the days went. A lizard came out on a big rock at a certain time every day. The beavers came out at a certain time every day, and the otters at another time. It took me three days to understand that a sound I heard every morning was a little shrew under the leaves. At one point, I looked down and slithering past my butt was a very large gopher snake. It was amazing to just watch sunrise and sunset.

works: What an amazing experience it must have been, to be so still and see like that.

Mark: To feel. I’d never done that. To feel the pulse of one place; to watch the light—and all the critters doing their magic.

works: One summer, I spent several days hiking in Point Reyes. My marriage had fallen apart and it was good therapy. Most of the time I was walking alone. After 45 minutes or an hour I noticed that I’d experience a shift. Suddenly, I’d be there. One morning I was walking in a coastal scrub area. It was sunny and very quiet and birds were flitting around. I stopped and just stood there very still. And suddenly, something came over me. It’s really hard to describe the experience. But it was very real. I felt that I was in their home.

Mark: Yes… [we pause] There’s something about

living in our earnest hamster wheels. We don’t see this miracle. And it’s our home as well. Yet, we don’t even see that because, “I’m off for a walk.” Right?

works: Exactly. Sometimes I find myself looking at my dog, Ula, and I’m suddenly astonished that such miracles exist.

Mark: Do you know the miracle of a bird? I mean, “Oh, yeah. They’re those cute little brown things right there.” We’re so amputated from it all. But be it a dog or a bird, it can open these doors of perception. Or a river: “Wow, this is fun!” It’s more than that.

works: [pause] This is such a big thing, I’m a little short on what to ask next, but I know there’s so much more. Does something come up for you?

Mark: Well, I’ll just say that from my Rose Creek experience last year, I realized it was that love affair that’s animated everything I’ve done since. I know the loss of a place, and I don’t want it to happen to any other place on the planet.

So when I started International Rivers Network,

I got to work with these amazing heroes who are trying to protect their people and their land. There are people in love with their places all around the world. I’ve been privileged to collaborate with so many of them. And now I’m trying to figure out what awakens us. What helps us reconnect and integrate?

I’ve done it through activism, and there are more and more positive trends of people getting connected and taking action. But it’s not vast enough. So we lose more and more, and yet it keeps happening.

works: Would you say something about starting the International Rivers Network?

Mark: After the Stanislaus campaign was fully over and drowned, I spent a year trying to raise money to rid the campaign debt. Sharon (my former wife) and I got married and traveled for 11 months, mostly in Africa and Asia. I was on the board of Friends of the Earth. We went to the international meeting in Europe, and then to East Africa, the Middle East and Asia. In each country, I visited people dealing with water. Prior to that, with Friends of the Earth, we kept hearing horror stories. Then I heard similar stories traveling the world.

After our year-long travels, I started International Rivers Network. It was such a profound time to connect with heros all around the planet speaking for their people and rivers. Randy Hayes had started Rainforest Action Network, a year and a half before. We’d go off to World Bank meetings. Our colleagues in Washington and around the world were using the World Bank meetings as a time to wake up the world, because the bank funded rainforest destruction and dam construction.

It was a remarkable time protesting on the outside, and then going inside and organizing. For ten years in a row, I organized the lobby efforts inside the World Bank, getting the grassroots activists to speak to these executive directors who steered development around the world. Do you know Vandana Shiva?

works: I know the name.

Mark: Vandana and I were housed together at the Friends of the Earth meeting in 1985. So we got to talk a lot together. And Sharon and I met Wangari Maathai, when we traveled around the world. Wangari was also part of Friends of the Earth International. In India, I remember meeting Anil Agrawal, who had been a journalist. He’d produced the State of India’s Environment. No one had ever done this before. It launched the environmental movement in his country. He gave me this incredible education: “You’re wondering why people protest when there’s a one percent rise in interest? That means in Colombia they’ll have to stop growing corn; they’ll have to start growing export commodities to pay the debt just for that interest rise.” At one point, he finally said, “Why do people in your country want to save rivers?”

I got quiet for a minute and said, “My sense is that many of us were raised in the city and we’re suddenly discovering what’s out there, and wanting to reconnect with nature.” That actually stopped him for maybe three seconds.

“In our country,” he fired back, “people don’t have to get back in touch with anything. They live with the sunrise, the sunset, and the rivers every single day of their life.”

And I realized that in America, the environment is out there. In much of the rest of the world, they’re not segregated issues. If you hurt the Earth, you are hurting people; if you hurt people, they are forced to hurt nature. Only in our deluded, “modern” Western perception have we segregated people and nature.

It was an amazing tour, and amazing to co-create with these heroes. I’d walked the corridors of Sacramento and I’ve walked the corridors of Washington. But these people, if they went to see their government to ask for changes, they could literally be disappeared. So it was challenging getting them to come in and share what they know. They have facts, figures, and information, but these World Bank executive directors didn’t really want to talk with these grass-roots people. But because they were getting enough bad press, the World Bank president said, “We should start meeting with NGOs.”

So I was able to talk the World Bank executives into meeting with our teams for 30 minutes. We gave them a constellation of our best activists and our most dynamic knowledge people and then related to their part of the world as best we could.

During one of the last years, I remember an executive director who said, “These meetings have been really important. The Bank has changed because of these meetings.”

It was quite moving to hear it come from him. He recognized we weren’t outside people who were protesting but were just trying to get a dialogue going so that they could get educated. The World Bank staff was just, “Move project, move money, move project,” but now they got to hear another side and things slowly shifted.

works: Where are you in your thoughts now?

Mark: I seem to be drawn to people who hold broad visions. I’ve got a friend, Mary Crowley, who’s trying to clean up the ocean gyre. She’s been going to oceans as long as I’ve been going to rivers. She has the maritime industry knowing what to do, and now she’s trying to raise the money to go out and start the cleanup.

works: Wow.

Mark: Don’t just wait, you know? Via the Pachamama Alliance, I met Clare. Her TreeSisters project is helping women of the North support women of the South replanting the tropics where forests have been lost, empowering women and normalizing the idea of planting trees in response to global warming. And Bill Shireman, who runs Future 500, is inspiring corporations to become green and part of the solution. He helped the president of Mitsubishi Motors become an environmentalist, and he’s done the same for other companies. So I’m drawn to people who have visions commensurate with the magnitude of our challenges.

The environmental movement has done the best they can, and to me, we’re wasting our time “fighting against.” So I’ve been trying to figure out how to mature and grow and deepen activism. With Gandhi it was, “I’m not here to fight you and I’m not going away. Your children aren’t going to be proud of what you’re doing here. I can see the ideals you espouse, and I want you to live up to them. You should go back home and practice that.” So that’s another dimension I’m intrigued with, how do we more frequently apply the power of love?

I had the experience of coordinating the Earth Day International effort in 1990 and 2000. In 1990, nine months after our organizing, there were 200 million people in 143 countries, including all the people in this country, actively engaged in the environmental actions for the Earth. People are hungry to be engaged. We’re at this remarkable time when there’s a deep yearning, and yet we still love giving our power away. Sorry folks, there’s no Them. There’s only us.

works: Yes.

Mark: I’ll share one last analogy that came to me. In running a river, there’s Class I through Class VI. Class I is flat water, easy—canoe. Class II, the canoe might tip over. Class VI, you don’t run because you die.

So those are the scales, right? Now to run a Class V river, you’ve got to have real good skill; you’ve got to have good equipment, and you have to know how to read the water. To run a Class V, you have to be able to see. You’ve learned how to interpret and read all of those water features, from the hole that can eat your boat, to the shredder rock just under the water’s surface, to all of the little things that, if you don’t see them, will spin you into one of the bigger dangers.

What makes it a Class V, is that there is a through-line. So once you’ve identified the obstacles, you put your attention on the through-line, because if you put your attention on the obstacles, they become magnets and pull your attention away.

To me, humanity is at this point—and most of humanity is in denial. We’re in a Class V, and it’s time to drop “aren’t they going to take care of it?”

Even though we’ve never been here before, we intuitively know something about what each of these gargantuan sharp rocks and holes are that can wipe out everything. In this situation it’s time to focus, “Okay, where is the through-line?” And we can only find it by working together. So it’s time to unleash our creativity and learn together as we go through terrain we’ve never been in before. So what shifts us from our disconnection toward opening our hearts and unleashing our gifts together?

This article originally appeared in Works & Conversations and is republished with permission. Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of Works & Conversations, an inspiring collection of in-depth interviews with artists from all walks of life, and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

On Feb 13, 2017 Immanual Joseph wrote:

Mark is an amazing human being. Pure passion! God bless his enthusiasm for preserving nature.

Post Your Reply