Emily Baxter: We Are All Criminals

Below is an edited transcript of Emily Baxter's Awakin Call interview

Below is an edited transcript of Emily Baxter's Awakin Call interviewAmit Dungarani (Awakin Call Host): Many of us have perhaps committed wrongs that we've gotten away with. These are privately-held memories without the public stigma that comes when we don't have a permanent record of our wrong-doing. Maybe we sped on the highway, or pocketed office supplies from work, or stole candy as a child. Typically we have ready excuses for all our questionable actions, big or small. "No one got hurt." "I was in a hurry." "It was only once." "I didn't know better at the time." As this week's guest frames it, "We Are All Criminals". Pavi, maybe you could start us out today by introducing Emily.

Pavi Mehta (Moderator):Absolutely. Thank you Amit.

When she was younger, Emily Baxter decided that she was going to pick a job where she could wear a hoodie to work every day and not have to do any public speaking. Then she promptly chose the field of litigation, found herself suiting up for court, and speaking passionately in front of judges and juries on a daily basis. Her deep commitment to creating a more fair and equitable world has led her down a demanding path. She served as an Assistant Public Defender representing indigent members of the Leech Lake and White Earth Bands of Ojibwe charged with crimes in Minnesota State court. She served as the director of advocacy and public policy at the Council on Crime and Justice in Minneapolis where she helped create significant changes, like "Banning the Box" and policies which directly shape how justice is enacted. A former Fellow at the University of Minnesota Law School’s Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, she is now a full time founder and director of the unusual nonprofit, "We Are All Criminals." It's a nonprofit that seeks to inspire empathy and to ignite social change through personal stories about crime, privilege, justice and injustice disrupting the barriers that separate us. She's a photographer, a storyteller and a woman with an incredible heart whose one-word message to the world is simply this: "Listen." It's a deep privilege to be able to put that wonderful advice into action today with her. Thank you Emily for the work that you do in our world and for being here with us today.

Emily Baxter: Thank you so much for that introduction and thank you for inviting me to join you today.

Pavi: Well, the pleasure is all ours. Before we dive into your present work, I'd love for us to get a snapshot of the journey that drew you into the justice system. Can you give us a flavor of Emily Baxter's back story? Where you grew up, key influences in your childhood, and -- did you always know as a kid that you wanted to work with the law?

Emily: Wow you're taking me way back here. No I certainly didn't always know I wanted to work with the law. In fact, for a long time as a child I just wanted to be a shark. So I guess that in some ways that led me down this path. I grew up in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. I come from a long line of teachers and farmers, so law didn't come into play anywhere until after undergrad. I had studied English literature and was working at a coffee shop, caffeineating the students on campus. A fellow employee there was studying for the LSAT. She wanted to go to law school. As I said, I grew up in South Dakota where there wasn't much to do other than get into trouble, and and take the LSAT for fun. That shows you just how boring life in Sioux Falls, South Dakota is when you're taking standardized tests for fun. She asked me to help her with this, and I gamely agreed, and through that mentoring realized just how low the threshold to getting into law school was. So I took the exam and got into law school and while in law school I was thoroughly bit by the criminal bug.

I had this incredible opportunity to work as an intern for the Hennepin County Public Defender's office in Minneapolis, Minnesota and there just really fell in love with the work. So, upon graduation, the first criminal-related job that was open was an Assistant-Public-Defender position on the Leech Lake and White Earth Bands of Ojibwe Reservation just north of the city. I worked there for some time. Absolutely loved it. It was exhilarating. It was exhausting. It was utterly maddening -- the deep injustices that permeated nearly every aspect of life for my clients, all of whom were Native American and all of whom were poor. After a while, it took its toll and I left.

I left public defense. I did so with the kind of naivety that you only have when you're in your 20's. I was absolutely certain that I could change the law, and that if I could change the law, I could change the realities for my former clients. So I started working as a lobbyist working in Criminal Justice Reform as a Counsel and Private Justice in Minneapolis, Minnesota and we worked on some really cool issues like "Banning the Box" -- removing the criminal-record inquiry from the initial job applications so that one with a criminal record would have the opportunity to get their foot in the door before being denied because of their history. We also expanded expungement law so people with more serious records -- other than just -- negligible records -- would have the opportunity to ostensibly get a clean slate -- although that's not a plausible reality in today's information age. Nevertheless, they would have a better shot at moving forward. But I found that that work just wasn't enough. Even when you changed the law, you weren't changing the hearts and minds of the people who were engaging with that law. So those victories, at least for me, seemed to fall short of the greater change that needed to happen. So during this time -- I can tell you a little about how this project kind of came to be. It was all in this time period.

Pavi: Just before you do that, you said something I think is really important - that you realized that there was a gap in being able to change the hearts and minds of people who engage with the law. Just to flesh out that picture for those of us who aren't as familiar, who are those people? How do those laws play out? Where is it that you were seeing that kind of gap?

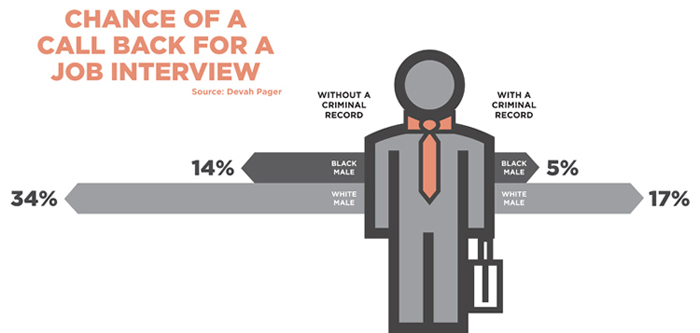

Emily: First, so that we're all kind of on the same page, the criminal justice system is a suffocating presence for many individuals and communities nationwide, and for others it's almost entirely absent. For example, we have more than two million people who are incarcerated in state and federal jails and prisons, and those are people who are currently in cages. Beyond that, we have millions of people who are on probation or paroled. They're under the thumb of the criminal justice system. Their liberties are curtailed, but they're living among us. They've in the community. Beyond that you have somewhere between 70 and 100 million adults who have a criminal record, and who bear that legacy of an interaction with the criminal-justice system. Their lives are defined by past mistakes and they are often unable to move on -- literally 100 million people are suffering because of this. Keep in mind that these individuals don't exist in a vacuum. They have sons and daughters. They have brothers and sisters. They have mothers and fathers, spouses and partners and greater community members who can all be profoundly impacted when someone is defined by a past mistake and not allowed to fully engage in society and life again. Now what's key to understanding all this, is that we are not all affected to the same degree. The criminal justice system doesn't touch all of us as profoundly and as devastatingly as it does others. For example, the lifetime likelihood of imprisonment for black men in the United States is one in three. One in three.

Pavi: Wow.

Emily: None of us should be okay with that. Meanwhile for white women such as myself, it's 1 in 111. Now, that's not to say that white women aren't committing crimes or haven't committed crimes. But that's just not who you see proportionately speaking in the criminal-justice system. Those disparities start early, with kids as young as five being criminalized, six-year-olds being taken into court shackled and paraded among county courthouses. And again that burden falls disproportionately upon African American, Latino and Native Americans throughout their lives. There's also a distinct disparate effect on poor communities. For example, there are more than 12 million arrests every year in the United States; 80 percent of those arrested are eligible for public defense. In some jurisdictions, in order to be eligible for public defense, you cannot earn more than $3,000 a year. Can you personally fathom living on that? I can't. That incredible level of poverty is just staggering. So that's who you see in our criminal justice system. That's who you see being caught in this dragnet.

.jpg)

Emily: I was not an incredibly successful lobbyist. Let's just be clear about that. I didn't spend a lot of time in the capital. It's not my strong suit. Instead, I spent it in my car. I went all across the state -- this was when I was living in Minnesota -- talking to policy makers but also to landlords and employers and licensing boards -- to anybody that I could get to listen to me about the need to create the capacity for second chances -- to hire individuals with criminal records, to rent to individuals with criminal pasts, to create policies that welcomed people back into the fold. Time and again I heard, "You do the crime, you do the time", and, "Once a criminal, always a criminal." So around the same time that I was trying to engage with decision-makers across the state.

Another part of my job was working as a rights-restoration attorney at the non-profit. We would hold these second-chance seminars in the basement of a government center, a small windowless room. There was one night in particular -- I'm sure the sun had long-since set -- when in walked our last participant. We'll call him Anthony. Anthony was incredibly nervous. He was sick with worry. You could tell that something was deeply, deeply weighing upon him. I thought as he was crossing the room that this man must have some extraordinary past, something like multiple aggravated robberies, maybe some federal charges, maybe manslaughter. There must be something that would bring about this amount of devastation, the feeling that he couldn't possibly move on. So when he handed me a copy of his criminal record, and when I opened it and saw that it was just a theft, and a relatively minor one at that, and I let out this laugh. "Even if the court doesn't expunge your record, it's not like your life is over." And with that, he started to cry. You see, earlier that day, he told me, he had contemplated taking his own life. What was "just a theft" to me, to Anthony was a lost job. It was missed housing payments. It was missed meals. It was door after door slammed in his face. It was the loss of respect of his friends and family, the loss of a sense of self, and the loss of hope.

I had become so cynical to the entire process that I just didn't see why anybody would be worried about a minor offense when in fact that minor offense was the thing that had been defining him since he picked up that record. As as he was telling me this, I thought back to those conversations with the decision-makers across the state, the people who said, "Once a criminal, always a criminal." And I thought, "How many times had I taken something that wasn't mine?" and "How many times had I gotten away with committing crimes?" and, "What does my race -- what role does my race, my class, my era and geography and gender have to do with the fact that I got away with it?" and "What would life be like if I didn't have the luxury to forget?"

So I started asking other people that same question: "What if you had the luxury to forget?" I picked up a camera and a recorder and hopped in my hatchback and drove across the state, now all across the United States, interviewing people in places where they felt comfortable enough to disclose to me something that they'd otherwise had that luxury to never tell. Then I'd take photographs of the individual, maybe of their hands, or a picture of their cat, or the contents of their fridge, something that shows an individuality and a personality but, of course, without identity. I then placed the first, I believe, 80 of those stories with those "mug shots" if you will online at "WeAreAllCriminals.org." You can see the collection of the first third of the stories that I've collected now.

Pavi: It's amazing. I'm trying to imagine how you went about doing it. Were you stopping strangers in the street asking for their "crime" stories? How did this organize? What did it look like as you began to collect these stories?

Emily: It was like a parade of failures for me. It was really interesting. The way that I got the first round of stories was through a flyer. I drew up a flyer that said: "We are all criminals. What if you had the luxury to forget?" and I left my contact information. I then sent that through our social-service network when I was still working at the non-profit, but I asked that network not to respond because I didn't want to hear from people that I already knew. Instead I asked them to forward it on to their friends, to their coffee clubs, their colleges, their church groups. I thought I could talk to people who were three- or four- or five-times removed from me. To my unending surprise, the phone actually started to ring. That was when I thought, "Oh my gosh. I better buy a camera. I need to get a recorder. I was not prepared for people to actually engage, and it snowballed from there.

Pavi: I've been amazed going to your site and reading these stories, it's a very broad cross-section -- you're talking to attorneys, you're talking to bank tellers, you're talking to doctors. And you're having these people reflect on what didn't define them, what part of their story didn't get amplified. And thank goodness it didn't! In the course of doing these interviews I'm sure most of the ripples happen invisibly and there's actually no way of capturing or quantifying them, but do you ever see or hear about how it triggers a change in maybe the way someone decides to hire, for instance? Does that part of the story come back to you?

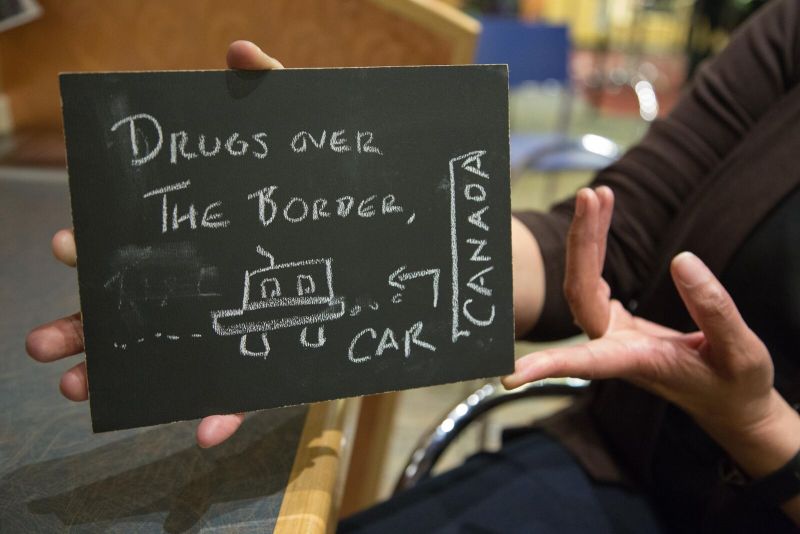

Emily: Yeah. Absolutely. In fact the first story that came to mind when you asked the question I'll tell you a bit about it. Recall that I said I had sent flyers out to the social-service network and asked the network to forward it on. That's what happened to this particular gent. He received the flyer after it had been handed, had been passed on by several other people so he was 3- or 4- or 5-times removed. This guy had no context for the overall conversation of mass-decriminalization much less the project of "We Are All Criminals." So he said when he got this flyer, he was ticked off. He couldn't believe that there was some punk in the cities who was calling him a criminal just because he was a member of the human race. So he said that for the first three weeks he would pick up his phone and dial all but my last digit wanting to call me up and chew me out. When he finally did punch that last number, he did so, not to complain but to participate. You see, he recalled that he used to run drugs across Lake Superior. How do you forget something like that?

You forget something like that when you think of drug trafficking as

something that happens between strangers in darkened alleyways, not something that happens between college friends. So what had happened was, his freshman year he left his hometown and went to a private school across the Lake. His sophomore year he transferred back to his home town and moved in with some of his old college friends who, it turns out, were no longer just smoking dope but now they were selling it. This guy was then the ideal conduit for the untapped market across the stormy waters because he knew who the potential smokers were, he knew who the potential narcs were. And so they trained him. He would often handle the communications. Sometimes he would run the drugs. He would take them money. He asked me after all of this if I thought that anything he did rose to the level of something criminal. Yeah. Yeah. Yes. It most definitely rose to the level of something criminal, on state level on federal level, not just criminal, we're talking felonious. This is something that you could have that could just completely change the trajectory of your life had you been caught and with that he just started to unravel.

something that happens between strangers in darkened alleyways, not something that happens between college friends. So what had happened was, his freshman year he left his hometown and went to a private school across the Lake. His sophomore year he transferred back to his home town and moved in with some of his old college friends who, it turns out, were no longer just smoking dope but now they were selling it. This guy was then the ideal conduit for the untapped market across the stormy waters because he knew who the potential smokers were, he knew who the potential narcs were. And so they trained him. He would often handle the communications. Sometimes he would run the drugs. He would take them money. He asked me after all of this if I thought that anything he did rose to the level of something criminal. Yeah. Yeah. Yes. It most definitely rose to the level of something criminal, on state level on federal level, not just criminal, we're talking felonious. This is something that you could have that could just completely change the trajectory of your life had you been caught and with that he just started to unravel.He started thinking, "Okay, hold on. Hold on. So, if I would have been caught, I wouldn't have graduated college. If I wouldn't have graduated college, I wouldn't have gotten that first internship where I met my wife. If I wouldn't have met my wife, I wouldn't now have my two sons. Okay," he said, "but, let's say that by some cosmic confluence I did meet my wife, I still did have my two sons, what kind of father would I be?" He said, for example, every year he fills out an application to volunteer with his son's hockey league team, and every year it asks the question, 'Have you ever been convicted of...' and lists ten offenses. And ever year he blithely checked, "No-no-no-no-no-no-no-no-no." He said if they were to ask "Have you ever committed any of the following?" he doesn't know how he would respond. He said if he had been caught, he said, "I don't know what I would do." He said, "I would have three options. Number 1, I could lie." Okay this is the gent that nearly got an ulcer from a flyer. He is not about to lie on the application because, if somebody googled him, they would find his record and he just couldn't do that. So he said that that was off the table. He can't lie. "Number 2," he said, he could check "Yes. Will explain." Now this man has been a business owner, and for the last ten years on his initial job applications he asked, "Have you ever been convicted of an offense?" and every time that box came back checked in the affirmative, he would chuck it because, he said, he didn't want to work with a criminal. He said, even more than that, even if he did try to explain, he knows how parents work and the stigma wouldn't just attach to him but it would run down through his sons and he wouldn't do anything that could potentially harm them. So, he said, he would have one option left, Option Number 3. He could just not respond. He could just take himself out.

Emily: I can't tell you how many people I've worked with over the years who have just stopped responding, who have just taken themselves out because you can only get that door slammed in your face so many times before you just say, "Enough." Now I'm not saying that people with criminal records can't be incredible fathers. They most definitely can. Mothers too, sisters, mentors, leaders. What I am saying is that, for the 75 percent of us who don't carry a criminal record, we're creating these barriers that lock out the 25 percent that do and sometimes we don't even realize we're doing it. Now this gent, after I interviewed him, after he shared his story with me, he then contacted me later to tell me that he had removed that question from his job application and that he was now hiring people with criminal records.

Pavi: That's incredible.

Emily: Yeah. There was another woman I talked to. She married quite young and before she even said "I do" she knew it was a mistake but they got hitched and, before long, he became abusive. She said that she did what most kids in their early 20's do when they want to be out of their own bodies. She would drink and drink into oblivion. After drinking, she would drive home. She had a million excuses for driving home. That he wanted the car home that night, that she was a better driver when she was drunk, that she couldn't afford a taxi home, that she needed the car the next morning -- whatever it was. She had a million of these excuses. After some time passed, she got a divorce and she turned her life around. She went into law enforcement, met her now husband on the force and really just found a new life, a new chapter, maybe even a new book. It was a few years ago, then, that everything came to a halt. She and her husband were driving back from a law-enforcement benefit when a car on the highway crossed over the median and, going 60-miles-per-hour, slammed into them. She said it was this explosion of air bags and engine and bone. Her husband was airlifted to the nearest hospital with a 50-percent chance of survival, and even now years later still is crippled in pain. She said that she herself got serious nerve damage because of this.

The driver, the man who blew I think it was like a point-26, he was terribly drunk, the 20-some-year old driver who crossed the median and slammed into them walked away without a scrape. She said that in the years following that, she was consumed by anger. She hated this man. She said that, if she could have found him, she doesn't know what she would have done. So she said, "Thank God I never did locate him." She stopped eating. She could hardly work. She was overcome with this incredible hatred towards this man.

And then she heard about this project, "We Are All Criminals" and she didn't engage with it willingly at first. But, after some time, she said she kind of opened herself up to the possibility that she was a criminal too and through that then realized that that man, the man who had crossed the median and slammed into her, that could have easily been her a hundred or a thousand times over before. She said that she's not able to fully forgive him yet but that she's working toward that and that as a law-enforcement officer, what greater thing can come from this than empathy and from understanding that there aren't two distinct categories of people, "Us and Them;" "Clean and Criminal," but instead, to recognize not just the common criminality that we all share but the common humanity and to allow those opportunities for true interaction with one another -- for second chances, but first chances too.

Pavi: That's a powerful story and it just gives me a glimpse at kind at what a privilege your job is...

Emily: Oh yeah.

Pavi: To be able to speak with these people must demand a high standard of empathy. I imagine the last thing you want to be doing is going into these situations and these interactions with judgment.

Emily: I should mention, though Pavi, to be honest, I have to constantly relearn that, because I'm not even aware of my own prejudices half the time. I'll sit down across from somebody and they'll start telling me a story, and it's not where I thought it was going, and I realize that I am just as guilty of constantly bringing that lens, that clouded lens that we all carry. It's a daily exercise to recognize that I'm doing it and to with, everything that I can, wipe it clean so that I can see that true person.

Pavi: I'd love to hear you unpack that a little bit. To share one of your own experiences of that kind of that shift, or a story that took a turn that you didn't see coming.

Emily: Wow. There are so many. There are so many that fall within that. One of the first ones that I was thinking of was a gentleman who is an academic, a very kind and calm and brilliant academic that I met. I wondered what story he had for me that would fit within the project. Every now and then I get people who say minor things that are still helpful, that "I stole a sandwich" or "I used to pad my tips with bills from the till" or "I downloaded music unlawfully" or "I drank underage" -- whatever it was. I thought that he must have something along these lines. Maybe he didn't return a library book or something. Instead, he told me that when he grew up, he lived in a rough neighborhood and his family moved to an even rougher neighborhood when he was 15-years old. He said that he found himself beaten and mugged several times within the first few weeks and that, before long, he realized that when he surrounded himself with a certain group of guys, the beatings stopped. So, he said, he did what perhaps many logical 15-year old's would do and he joined the gang. That didn't come for free. The price was exacted one Saturday afternoon when he was told that if he didn't pick up a lead pipe and beat a child that looked a lot like him, another 15-year old boy from a rival gang, that he himself would be beaten. He said that he made the decision that day that he's regretted ever since and that, in fact, at least once a month in the middle of the night, he wakes up screaming thinking that it's all happening again. He picked up that pipe and he hit that child.

If he had been caught, he would been certified to stand trial as an adult. He would have been convicted. Once convicted, he would have entered the system and eventually gone into prison and then come out and then gone back in and come back out, that kind of revolving door that happens to millions of Americans. He wasn't caught. He graduated from high school. He got a scholarship to go to college where he said, for the first time in his life, he was able to read a paragraph. He could complete a math problem because, for the first time in his life, he wasn't constantly checking over his shoulder to see what was coming next. He could concentrate. He was safe. His grades skyrocketed. He went on to graduate school and now has a PhD in biophysics. I would have never guessed that this man carried so much with him. I would have never guessed that he would have picked up that pipe. I would have never guessed that he had grown up in poverty. He seemed as privileged as most of the other academics I know. It helped further validate two things: 1. You really cannot begin to understand another story unless you listen, unless you ask and listen; and, 2. that there are so many people across the United States whose futures are foreclosed before their brains are even fully developed, kids who are born into situations and environments that are wholly different from what I experienced. They're robbed of a future before they can even fully-enjoy the present. So, I think that really took me back.

There were others too. There was one woman -- I learned to ask different questions because not everybody identifies their criminal history as criminal. There was one woman that, when I asked her what she had gotten away with, said, "I've got something of a rap sheet for which I was never caught." She listed off fairly common things like drug use and drug paraphernalia and driving while buzzed and things like that. Then I asked her if there was anything that she did that wasn't criminal but just something that she felt kind of bad about. She said that when she was 18-years old, she tipped over a port-a-potty with somebody inside. It was a girl that she really didn't care for. She said that the excrement went all over this girl and that she felt horrible about it -- this is decades ago and she still feels horrible about it. She's a social worker now. She's dedicated her life to helping people, but she holds this memory. So I told her, "You know that's a felony, right? You know, 'Assault with bodily fluids.' among many other things." She would have been barred from her profession but she didn't realize it. There again, I wasn't expecting that kind of story from her and I've heard that time again from people.

So part of the project is the constant reminder to myself to just be quiet and listen. And I realize now that I've been talking at you for an entire hour.

Pavi: No, no! That's what you were invited here to do. Before we open up to the questions from listeners, I did want to have you speak a little bit about the flip-side project that you have going that we haven't touched upon yet, but there's a lot there. You have another project called "More than My Mugshot" is that right?

Emily: That's exactly it. So there I interview people who have been caught, but the focus isn't on their criminal history and it's not really even on how that record has affected them moving forward. Instead what we focus on are the positives by which they define themselves. What's more relevant to a background check than your eight-year old record or your ten-year old record or your two-year old record? What is it that you could bring to the table if were just allowed in the front door. So thinking back to Anthony for example, the gent that I met in that horrid basement in the government center in Minneapolis -- Anthony is defined by his criminal record, right? He's a "thief." But he's truly a father. He's a caregiver, a nurse, a speaker of six languages, a survivor or genocide, a volunteer coach and an avid reader. Yet, you would know none of that if all you saw him as was a criminal. My hope is that, through this project, we can see people not defined by their worst moments but by their true worth. Give Anthony that luxury to forget and the opportunity to be forgiven, to not be tethered to his past but wholly able to live in the present and to dream of a future. So that's what "More than My Mugshot" is about.

Pavi: Thank you so much for sharing that Emily. Now, I could go on asking questions, but I know that there are already questions that have come in, so I'm going to hand over to Amit who can help get those out there.

Amit: Yes. Thank you Pavi. Thank you so much Emily. We actually had a comment that came in online from "Priya" whose listening in from Chennai in India. She asks, "Have you asked people who were part of the legal or enforcement system some of these very same questions? Have they done anything that they felt about they've gotten away with it that could have been considered criminal? What did they have to say? Going into that conversation with you, did it create a shift in their work or in the system itself?" I know you had shared the one about the young lady who eventually went into law enforcement, but if there was anything else that you have, perhaps, a story to share?

Emily: Yeah. It's kind of a funny story. So, I was giving a lecture, a

"CLE" a Continuing-Legal-Education class, and it was near the Capital, and so there were were policy makers that were coming in for their free CLE credit. This one gentleman came in, crossed just in front of the stage and sat down in the chair furthest from the door. This is in Minnesota, by the way, which is key to understanding that when I began to flash the PowerPoint that said, "We Are All Criminals," you could tell that this guy was in the wrong room. He did not want to be there, but he's in Minnesota so he's not going to get up and leave. He's polite. Instead, he just shot me daggers for the entirety of the half-an-hour or hour talk. He was clearly uncomfortable, clearly didn't agree with what I was talking about, and I kept my eye on him because at the end of the talk I wanted to engage with him personally just one-on-one because I think that the notion that we've all committed crimes is not a novel one by any means and it's really not that complicated. Once you understand just how over-broad our criminal-justice system is, you really do understand that you cannot live for any appreciable amount of time in this country without violating multiple laws. So, after the talk, I made my way over to him, but he saw me coming and bee-lined it out the door. I was starting to walk after him when two other legislators stopped me and said, "He's a lost cause. We've tried to engage with him. Don't worry about it." I felt defeated, like "How can I get to this man?"

"CLE" a Continuing-Legal-Education class, and it was near the Capital, and so there were were policy makers that were coming in for their free CLE credit. This one gentleman came in, crossed just in front of the stage and sat down in the chair furthest from the door. This is in Minnesota, by the way, which is key to understanding that when I began to flash the PowerPoint that said, "We Are All Criminals," you could tell that this guy was in the wrong room. He did not want to be there, but he's in Minnesota so he's not going to get up and leave. He's polite. Instead, he just shot me daggers for the entirety of the half-an-hour or hour talk. He was clearly uncomfortable, clearly didn't agree with what I was talking about, and I kept my eye on him because at the end of the talk I wanted to engage with him personally just one-on-one because I think that the notion that we've all committed crimes is not a novel one by any means and it's really not that complicated. Once you understand just how over-broad our criminal-justice system is, you really do understand that you cannot live for any appreciable amount of time in this country without violating multiple laws. So, after the talk, I made my way over to him, but he saw me coming and bee-lined it out the door. I was starting to walk after him when two other legislators stopped me and said, "He's a lost cause. We've tried to engage with him. Don't worry about it." I felt defeated, like "How can I get to this man?"Two weeks go by, and in the local newspaper there's an Op-Ed written from this legislator and it says, "We Are All Criminals" and in it he says that we need to seriously reconsider our criminal-justice system and the policies that perpetually punish people. It was an incredible Op-Ed. From there then, he supported second chances, he co-authored bills. This guy is amazing, and I'd like to think that this project had something to do with that transformation. So yes, I have reached out to the very people who are penning the laws and there has been good movement.

Audrey: Hi this is Audrey calling in from Berkeley, California. My question was actually related to how, earlier on, you mentioned that when you got into criminal law and your winning policies or changing policies didn't really change the hearts and minds of people the way that you thought, and so it felt incomplete. So I'm wondering now, after you've engaged in this project, and engaged with the mind and heart of people and yourself, has that influenced the way that you view or work with law now or policy now?

Emily: Wow. That's a really good question. Thanks Audrey. I think that it has. I realized that -- first of all I should say that there are advocates and activists who rise every day to do amazing work and who change the laws and who do change the hearts and minds of many people and I respect them so much. The problem was that it just wasn't fulfilling for me. I didn't feel like I was doing the work that I could do well. As an attorney and as a lobbyist and an educator, I used to focus so much on the statistics and statutes. Through this project, I've really come to understand the importance and the poignancy of stories. So, this project, then, kind of exists at that intersection of statutes and statistics and stories. It's changed the way that I interact with policymakers by bringing stories forward first and then backing those stories up with the facts and figures, and underlining an urgency for change, but the focus is really always back on people.

Amit: We have another individual that's writing in from Illinois and wanted to know, "Of all the rights that are taken from felons, why is voting one of them?" How does that come up in the stories that you've come across or the reflections whether it's with individuals or people in law enforcement or policy?

Emily: Yeah. That's a great question. In part, because the law is different throughout the United States, there are some jurisdictions where individuals never lose their right to vote, and then there are some where they'll lose the right to vote permanently after a felony conviction. The justification for that is old. It's the idea of social exclusion. It's the idea of civil debt, that you have forfeited your right to weigh in on community matters because you have betrayed the community. In many states, those laws were put into policy back when there were only a handful of felonies on the books and only a handful of people who were convicted of those felonies. Now you're taking about millions of people nationwide that have lost the right to vote who can no longer engage not just in these huge elections, the elections that would have turned out differently, like the Bush v. Gore election for example. There are criminologists and sociologists say that, if the voting laws had been different in Florida, we would have had a starkly different outcome for that particular Presidential election. But there are also local elections, school boards and city council members, park boards, that have a great impact on people's everyday lives and yet they're not able to cast a ballot because of this Scarlet Letter, this mark of Cain, that they carry along with them. There has been some really awesome research, I think it's by Dr. Christopher Uggen from the University of Minnesota who looked at voters in the Pacific Northwest -- if I recall this correctly -- he had two groups of probationers, some who were allowed to vote and some who were not and, for the group that was allowed to vote, they had a reduced recidivism rate. They were not engaging in crime. They saw themselves as contributors to their community rather than as detractors to society, and so there is some pretty cool anecdotal research as well as this broader academic quantitative research that shows just how beneficial that rights-restoration is, that re-enfranchisement is for people.

Amit: So what is it that you hope people do once they've shared their story? It's easy to say, "Oh yeah I was a kid and I stole a piece of gum from a convenience store". It's easy for us to write that off because we don't want to confront that hey maybe we made a bad decision or had a lapse of judgment. So where do we go from there?

Emily: I think first is that the way in which you engage the question, right? So, perhaps the listeners today have recognized something of themselves from the stories that I've told, or perhaps through other memory triggers they've recalled past transgressions. So first, there's that -- recall what you've done, and it doesn't have to be something that you're ashamed of. It can be something that you're proud of. It can be something that's completely unmemorable. It can be something that you didn't even realize was an offense, but now thinking back on it you can see that if you viewed it with the lens of criminality, "Oh yeah. That's a felony." Then, take note of the context that you allow yourself when you are recalling that memory. "I was young. I was drunk. I was stupid. I was in a bad relationship. I gave it back anyway. It wasn't my idea. No one got hurt." Whatever that context is, recognize that it may have existed for somebody who was caught as well. Now it's not necessarily an excuse, but it is an opportunity to recognize that common humanity. Then take note of the privilege that you've experienced, be it race or class or gender or geography or era or luck, and acknowledge that not everybody has been able to benefit from that same privilege. Reflect upon how patently different your own life could be and recognize how drastically different life is for individuals who were caught. Then, take action. Look within your own realm of power. You don't have to be a policymaker in order to make waves in this.

We can take action in ways big and small. We can take action in our own backyard and we can take it across the country. It's just a matter of looking into your own realm of control and finding where you can make those changes, where you can open your heart and your mind to somebody's true self. Does that make sense?

Amit: Yeah. Absolutely. I wanted to talk a little bit more about the More than My Mugshot project. How are you actually coming across some of these individuals.

Emily: I have been reaching out to prisons, but that isn't just the population that I'm seeking to engage. It's interesting. People with criminal records are more willing to tell their stories than those without -- I'm sorry -- people with criminal records. So the "More than My Mugshot" participants have been more willing to engage or more readily willing to engage I think than people that have had the luxury to forget, and yet they have had a more difficult time telling their story. This is just a generalization, there are of course exceptions. But generally speaking it has been harder to pull stories from people who are participating in the "More than My Mugshot" phase, and I think it's because they are so used to defining themselves by what they're not. They're so used to having to explain their criminal histories that they don't get the opportunity to really discuss who they are outside of that context. So, I hear a lot of stories about how people are no longer engaged in crime or perhaps who are sober or whatever that might be, but it takes a long time to get people to tell me that they make the best sweet potato pie in the county or that they grow the best tomatoes or that they put three of their grandchildren through college. There was one gentleman that I interviewed -- it took him 18 minutes to remember that he had been a medic in the US Army. This man had saved lives. If I had done anything like that, I would lead off with that! I would have kind of rested on my laurels like, that should be enough. But for him, he was so used to explaining that he's not a criminal or that he battled a lot of substance abuse -- and now he wasn't using. It was difficult for him to re-frame himself in a more positive light.

I'm actually working on a book about this project, and you'll be able to read more of those "More than My Mugshot" stories and see how they are the flip side to a lot of these luxury-to-forget stories.

Amit: Do you do any kind of outreach work with classrooms or anything of that nature where you can actually bring individuals from both sides of the coin?

Emily: Hmm. It is a little bit more difficult to get people who have had the luxury to forget to stand at a podium and take the mike and tell people what they've done, unless it's something minor, unless it's something that happened decades ago, unless they're, say, a celebrity and the news is already all over it. Because I'm a former public defender, I also get very nervous about people disclosing in a public manner what they've done because I don't think individuals understand just how devastating that can be. You know, one of the first participants of the project was a woman who blew up a port-a-potty when she was just a teenager. She's a pediatrician now, and if her identity were to be found out, she could potentially lose her license,​even though she was never arrested, but the act of arson would be enough and that confession of hers would be enough to bar her from the field. Then you have people who don't realize that they could lose grants or get kicked out of school or lose housing because of an admission to wrongdoing. But yes I do think there's value in sharing.

Amit: I wanted to share one last comment from of our listeners, Smita from Boulder who wanted to say, "Emily, Amen sister. I have loved, loved, loved all that you have shared this morning, your authenticity and the truth you speak has put in me tears. Thank you."

Emily: Aw. You have me tearing up. Thank you.

Amit: Thank you. I was wondering, is there anything that we as the ServiceSpace community or a community of listeners out there that can they can do to support you in the work that you're doing?

Emily: Well I am still actively taking stories. You might be my next new favorite participant. So please do email me. You can find my contact information on the website at WeAreAllCriminals.org. Beyond stories, I would love to hear your direct feedback. This is a project that is constantly growing and changing and I think getting stronger in large part because of the feedback that I receive from people who care deeply about the issue. I would love to hear from the listeners. I'm also, as I said, I'm working on this book which I hope is ready to be in people's hands by the end of the year and I would love to come out to your communities and talk to your colleges or to your church groups or to your places of worship about the project and about the need to engage in second and first chances. So please do contact me.

Amit: Wonderful. Thank you Emily.

(all photographs courtesy WAAC)

This article is an excerpted transcript of an Awakin Call conversation. On a weekly basis Awakin Calls bring together a global community of listeners who start with the idea that by changing ourselves, we change the world.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On May 11, 2016 adele Azar Rucquoi wrote:

Emily, thank you for your precious and truthful thoughts. My husband of twenty-four years (wonderful years) spent almost ten incarcerated in Florida's prisons. I'm writing our story and if you ever want to read the book we hope to be published, my email address is adelediane@cfl.rr.com.

Bless you and continue your good work.

Adele

P.S. His public defender saved him from the "chair" for which I'm eternally grateful.

On May 14, 2016 bhupendra madhiwalla wrote:

One is not a criminal until caught. Yes, we all have committed crime, knowingly or unknowingly, however small it may be. We all are judgemental. We point our index finger to all and sundry ignoring and without taking care of those three pointing towards own-self. Almost all of us are sympathetic but very few empathetic. All convicted do not live with the stigma and others should not remind one about one's conviction. To hire or not to hire is an individual's choice. We Indians are witness to several other types of discrimination which are not in developed countries and hence one more does not matter much. Often the laws are evolved which are contradictory to basic fundamental nature and those laws get violated easily and in-advertantly as some will always be out of the majority or average group. To make laws exhaustive and inclusive will mean no laws at all to be legislated which is not possible nor advisable. Dilemma. Hence crime will continue and will reduce only if poverty is reduced, discrimination avoided and quick justice is delivered.

[Hide Full Comment]Post Your Reply