Interview: Stephen De Staebler

Stephen De Staebler

John Toki encouraged me to interview his old friend and mentor, sculptor Stephen De Staebler. The following conversation is distilled from three meetings with the artist at his home and studio.

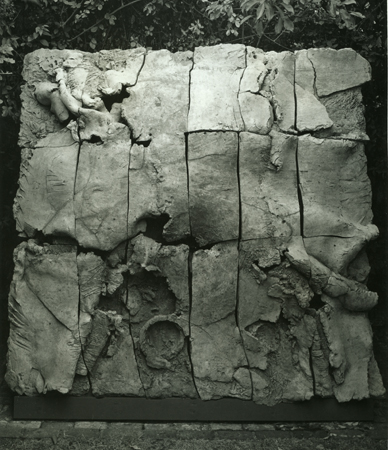

Stepping through the high redwood gate at his home, I found myself in another world. Several of De Staebler's ceramic figures stood around his pool, along a walkway to his studio and scattered in the landscaping as if waiting to be placed in more considered alignments. It seemed I'd stumbled upon an archeological site full of relics, ancient fragments and timeless figures halfway gone or partly restored, poised between here and now-and a distant then. Had they been rescued from the slow process of disintegration or were they poised for some new resurrection?

De Staebler greeted me and something about his ease affected me immediately. There's a quality about him, I found, a presence, that's quietly irresistible. One falls under the man's spell, which even now, two years after our first meeting, brings a smile to my face.

Before beginning the interview, could I look around? Certainly. We visited the studio and as we talked, whatever anxiousness I'd brought to our meeting simply evaporated. And soon, I found myself being drawn out, unusual when I show up in the role of interviewer. Before long I was telling Stephen about my own experiences with clay and ceramics from years past. By the time we sat down to speak for the record, our conversation had come around to the legendary potters Shoji Hamada and Bernard Leach. I asked De Staebler if he liked Hamada's work...

Stephen De Staebler: His work doesn't do much for me, but I like some things he said. He kind of teamed up with Leach and they made quite an impact on Western potters. I think that's the modern beginning of sensing the richness of clay in its own nature. You don't have to transform it into something else to find beauty. You have to burn through a lot of pretty work in order to love the gift of the clay-its randomness, its tendency to crack and warp. All the things that the perfectionists think are negative qualities are actually positive if you approach it from a different aesthetic.

Richard Whittaker: That's an aesthetic you appreciate, I take it.

SDeS: Well, I had this conversion experience. You might call it that. When I was at the Union Settlement house in New York City working as a group leader, I went over to the Brooklyn Museum School and took a ceramics course with Hui Ka Kwong. He was not a wildly unfettered ceramicist, but he was very good. Then when I came out to California, I got to know Otto and Vivika Heino. They invited me to come to their class at Chouinard. So I got my hands in the clay again. So this went on in my life. Periodically I'd find a way to get my hands in some clay.

When I started graduate work at UC Berkeley in 1958, I didn't have the thought of becoming a potter at all, but I got very attached to the idea of becoming a sculptor. The first course was a figurative modeling course taught by Jacques Schnier. After two weeks I discovered that I couldn't leave that studio. I'd still be in that classroom until nine, ten, twelve o'clock at night!

After that semester I took a course in ceramics with Peter Voulkos. He came to UC Berkeley the fall of '59 and I took that very class. [pauses a moment and laughs] I love the irony of it. Somehow I'd gotten it into my mind that if you really wanted to become a serious artist, you went to Europe to get your grounding. So when I'm in this stupid state of mind, who do I meet but my true mentor? He was right there, virtually across the hall!

I hadn't a glimmer of an idea that you could be a sculptor and work in clay, at least in a serious way. So I got all that established immediately when I got together with Voulkos. Peter Voulkos was my great inspiration. I'm so grateful to him!

Anyway, I was a very tight, fussy worker in clay at first and then, after hefting tons of clay around to try to make a sculpture big enough to compete with other ones going on, I left fussiness behind forever.

RW: Was that the conversion experience?

SDeS: No. The conversion experience-it's too formal to make it one event. For the first two weeks, Pete didn't say a word to me. He didn't say a word to anybody. His main obligation, as I learned later, was just to have two big, wheeled dollies loaded with mounds of clay. He had a big clay mixer like the one I gave John [Toki]. Jim Melchert was the TA in that first class and he really mixed big mountains of clay. So when class started you could walk over with a cutting wire and slice off as much as you could carry and waddle back to where you were working.

So I was working away on this bird, a big sculpture, about a yard across. Pete finally came over and looked down at this sculpture. He said, "What is that, a turkey?" [laughs] I found it pretty funny. My ego wasn't hurt at all. Then I tried making a sculpture around a wooden armature inspired by John Mason's work. I had my armature and I'd built slabs of clay about three quarters of an inch thick and about two feet by two feet. I had this mental picture of what this slab was going to do on this column of clay, but when it actually hit the column everything went wrong. You get pissed, and I was about ready to rip it off, but before I could do that, I saw what was there. What was there was this landscape! An undulation of clay that you cannot finesse. The only way you could make it happen is through an event-like the failing clay sliding down the column. So I think that's when I really discovered landscape. I would ponder this over the years. Traditional landscape painting has been around since day one-the Greeks, the Egyptians, the Assyrians. Everyone from that level of culture had landscape paintings. But what about landscape sculpture? I still defy anyone to come up with a landscape tradition in sculpture!

RW: That's an interesting point!

SDeS: For the first ten years, I don't think my work was recognized as valid for that reason. They were mostly floor pieces, although I discovered that I could make a piece on the floor, fire it in sections, and then mount it vertically. So you could have it both ways.

I took advantage of my old studio, which I had for twenty-five years in Albany. I put up a jib boom crane with a clearance of about twelve feet. You could climb out on the boom and pull yourself around by grabbing the rafters on the ceiling and, in my mind's eye, I could turn anything on the floor into something vertical. It was just an exercise in spatial configuration.

In fact my first big commission was a wall about eighteen feet long and about nine feet high for Salt Lake City. I just had room on my studio floor to do this. I made special easels that were about eight feet square. I had them balanced in such a way that I could get behind them and tip the clay slabs over onto the matrix on the floor, which was the substructure of the clay. I got some incredible events in the clay. Just incredible!

RW: The eight foot square piece would fall?

SDeS: Right. Slam! Onto the matrix, which was another colored clay, a continuous slab with ribs that intercepted the eight by eight slabs. This was done in several sections. That became the basic form. For the most part I didn't do any hand forming.

Then the next level of forming came from covering the clay on the floor entirely with paper or these murky plastic bags so I couldn't see what was underneath. I'd take my shoes off, and whatever else I had on, and I'd jump around on the clay, throw my body onto it. No peeking! All or nothing! Then I'd peel the paper and plastic away and see what I got. For the most part, I couldn't even touch them again they were so fantastic! [laughs]

Then, in the next year or two, I was doing this reclining figure, and the pelvic area was a kind of critical part of the sculpture. I climbed up on the mezzanine of the studio and I jumped, feet first, onto the clay in progress. It turned into this incredible pelvic area. What made me think of that at all is this little balcony in my studio here [points]. Actually, I only tried jumping from that one once. I guess I'd gotten just enough older to realize this is risky business.

RW: It's pretty far up there.

SDeS: It's about nine feet.

RW: Well, going back, I don't feel that I understood what you meant when you said you had a "conversion experience."

SDeS: Let me give you one example. Before I got very far into studying sculpture at Cal, I took a class at Berkeley High Evening School. The things I did were absolutely trite. I'm so glad they're no longer in existence! [laughs]. And I hadn't seen through that until taking Pete's course.

RW: So one of the conversion experiences then was about meeting Peter Voulkos and having his class.

SDeS: Yes. And the other would be the actual content of the clay when it acts through natural forces. But the main thing was being around Pete. He had real charisma.

Another story. When I got out of Cal in '61, I found a studio space in Albany and built this big, one hundred ten, one hundred fifteen cubic foot kiln. The piece I described making on the floor for Salt Lake City was fired in that new kiln. On the very first firing I looked under the kiln and there was this shattered section, all these shards. This was a disaster! The piece had gotten too hot too fast. So I called up Pete. Can you come over? So he came over. He looked at it. He chewed his lip. He took different postures.

I said, "Pete, what do I do?" "Pray!" he said [big laugh]. Pray! And it worked! [more laughter] I didn't break any other pieces in that sculpture. It was a great kiln.

At the beginning, because I'd been schooled in good kiln, bad kiln, I thought this was, by any yardstick, a bad kiln. There was no way in the world, when it had shelves in it, that I could get the heat up to the top. Usually kilns fire too hot in the top. Well, whenever I fired one big piece in it, it fired evenly. But if I had several shelves in it, like for the Salt Lake City relief, the heat always stayed at the bottom. But the gradation in the color from a cone 9 reduction firing to, say, down even to cone 01, was beautiful! You'd get these pale tans and grays.

RW: That's a lot of variation in temperature!

SDeS: Oh yeah! I then became so taken by it that I would position sections of a multi-section sculpture according to where I wanted it to reduce. Even though the size of the fired sections would vary depending of the difference in temperatures. Of course that never was anything that bothered me. In fact, I sometimes liked that variation in the tightness of fit of sections, if you see what I mean.

RW: What is it that's so appealing about the unevenness and the accidental?

SDeS: That's it. When everything is flowing, it doesn't matter whether it happened because you let the clay have its head-now, or later. It doesn't matter if you fired a section too high or too low. You have great latitude. But after having more and more experience I would have a more seasoned hope about how it might fire or how it might shape from the wet clay.

It's nice to work big. It involves your whole body in the process, like jumping on it.

RW: Could you say a little more about the involvement of your whole body?

SDeS: Well, the body is our sculpture. We live in our body like it is an animate sculpture. The fact that most art in civilization has been figurative is not by accident. When you're more aware of your body, you're more on the edge of survival. Look at Lascaux.

Clay has this great potential of responding to whatever forces are imposed on it. Most sculpture dies on the vine, from my point of view. It kind of follows a formula that says clay should be this. My attitude is forget about what it ought to be and do what wants to come through you.

RW: So some of that comes through the body, right?

SDeS: Right. I mean, it's a strong case for not separating body and spirit, for keeping them informing each other. If the work gets too cerebral, it can be beautiful, but it doesn't have this urgency that clay can offer in the figurative image.

RW: This gets into the whole area of what can come through the body. This seems to be an area that we don't understand much about, but it's a very interesting area, isn't it?

SDeS: While you've been talking, I realize that my first conscious awareness of my body in space came through falling in love with playing basketball. I had an incredible experience in high school made possible because the varsity coach was always looking for a couple of small players on his team. He liked to make great racehorse teams where you run your tail off. Having to improvise your moves at that speed required a special kind of at-one-ment. So even though I was small, I made the team. I'd be all over the court, intercepting the ball, stealing it, taking fast breaks! There's nothing more satisfying than being up against some hotshot opponent, say six-foot three, which was big back then, and stealing the ball from him. These big guys, you know, they have egos. If you're in just the right position, you can just tip the ball off their hands and steal it. They get so mad, they lose their cool [laughs]. We were good. We came within a sudden-death, double-overtime of winning the state championship!

RW: Wow! What state?

SDeS: Missouri. Basketball is taken seriously there. I made the second all-state team. It was a peak experience. When I say casually to people that "I learned more about art playing basketball than taking art courses" nobody ever understood what I meant. I never was really able to articulate it well. The thing about shooting a basket is that you have to sort of transcend your mind. It's all visual and spatial. So if you're going to groove as a player, you have to get into a space and a rhythm and endurance that is the same sort of thing it takes making big clay sculptures. It's similar for me, anyway.

There's an excitement in moving in space. That's why I think I developed ways of jumping on clay, stacking them until they wanted to fall down.

[laughs] In that first course with Pete, I kept making these pieces all in one day. Of course the clay needed to get stiff and I wasn't giving it a chance. So they would always collapse. So you'd build the next one up and it'd collapse. So finally I thought, I'm just beating my head against the wall. That's when I first got the idea that working with clay could be very much like gardening. You have to come into the plants at just the right time. You don't want to give them too much water, or starve them for water. So you have to time it. So that means you're working on certain ones over here while those over there are just taking root. So there's a similarity working with big clay sculpture and with the natural process of growing things. I've pumped a lot of clay in my day. The only person I have a real good friendship with who comes close is John Toki. John puts me to shame! [laughs] What is that, a twenty-three-foot-high piece of his? He just thrives on hard work.

RW: So true. John's great. Now I'm intrigued by how you learned more about making art by playing basketball than by taking art classes. I love that statement.

SDeS: Good. I'm just realizing that another way to express this is from the common phrase "second wind," another flash of energy to carry you along. This is exactly what would happen in every basketball game I ever played in! You'd run and squander your energy at first, because you knew you were going to get your second, your tenth, your twentieth wind! Now every time you get into another echelon of wind, you get into a freer state of mind.

RW: Now, your undergraduate work was at Princeton and you were drawn to theology, according to what I've read.

SDeS: Well, I've got to correct that. I ended up majoring in the department of religion, but when I went to college as a freshman I was all set on going to an art school. My father persuaded me to take a liberal arts approach. I said well, if I'm not happy making art on the side, I'll transfer to the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Art. But by the time my sophomore year ended, I was as happy as anything taking courses I liked, reading Dostoyevsky and important literature and getting in enough time to make a stained-glass window.

So in my sophomore year I wasn't thinking at all of going to an art school and, get this, they didn't have a fine arts department anyway! They do now. Back then they had an art and archeology department that had some courses in art history.

RW: We're talking Princeton, now, right?

SDeS: Yes. There was no formal hands-on art training. But they did have a resident sculptor named Joe Brown, a fantastic guy! He was a former boxer, so he had that sense of that energy needed to be a boxer-and a sculptor.

At any rate I stayed on at Princeton, but in my junior year, I couldn't do my artwork. I couldn't do my research and it was a horrible experience. I had never encountered an obstruction like that in myself before.

RW: What was that all about?

SDeS: The academic demands were heavier. I couldn't pull it off. So my way out of the conflict was just to change majors. When I began in full earnest in a study of religion, I wasn't real happy. I can study religion up to a point and then it becomes too removed from my own personal experience, secondhand. But for my senior thesis-and you had to have one to graduate-I did mine on St. Francis of Assisi. He's a fascinating character, much more interesting than the gentle monk who is feeding the birds. He said tanto sa, tanto fa (you know as much as you do). Doing was more important than theology.

RW: So there must have been some early experiences that led you toward art and toward religion. That doesn't come out of nowhere, right?

SDeS: Are you especially interested in religion?

RW: I'd say so. I think it goes back to my own experiences. That's why I was thinking you might have some. I remember, for instance, an experience as a teenager. I'd driven up into the San Gabriel Mountains and was sitting there alone looking out over the mountains and really pondering being here on this earth. After awhile, I got this unexpected sense that being here was not home, but a foreign place. What do you do with an experience like that? I'd say it falls somewhere in the realm of religion.

SDeS: That's it. I think we've been brought to think there are little cubbyholes for everything. But truer religion thrives on the question that you'll never resolve. If you don't honor the potential of one of these other levels of reality, you feel that somewhere down the line you're going to regret not trying to connect with it. And you carried this sense of not being part of the created world?

RW: That feeling did not persist. The memory is there, but what do you do with such moments?

SDeS: Well, society doesn't help us in that regard.

RW: It occurs to me that you became an artist. You went into the arts and...

SDeS: And that was precarious.

RW: That transition was precarious?

SDeS: Yes. But I was always thinking of myself as an artist, even as a boy. Somehow my parents got to know one of the faculty members of the Washington University Art Department in St. Louis, a wonderful man, Warren Ludwig. Everyone called him Gus. He liked me a lot and over several sittings he painted my portrait-wonderful oil technique.

World War Two erupted and Gus was drafted and ended up in the infantry. He was in jungle warfare and he came back a gray man. When my mother died in 1950, Gus and I spent some time together again thanks to my dad. Well, it's a complicated story. I'll have to get into my Black Mountain days. Have I told you about that?

RW: No. I don't think you did.

SDeS: It's getting off on a long tack, but you seem to be an indefatigable listener [laughs]. In the summer of '51, at the end of my first year at Princeton, I went to Black Mountain College. I was having a wonderful time. But, halfway through I had an experience with Robert Motherwell that made me so angry I packed up and caught the bus from Black Mountain to southern Indiana where our family farm was. And so instead of being involved in painting, I decided to build a boat. It was styled on the Cajun pirogue. I built one from scratch with hardly any knowledge of working with wood.

RW: Oh, yes.

SDeS: This was shortly after my mother's death, which I took more deeply than I knew. My dad sensed that and he was worried about me being alone. So he asked Gus Ludwig to join me at the farm and Gus and I finished off the pirogue together. I have it up in the studio [laughs]. Everything that matters to me is within a stone's throw!

That was one of my last experiences with Warren Ludwig. He was the one who opened the door to being a real painter. He gave me real Shiva oil paints in tubes and Windsor Newton watercolors, in tubes. He gave me a wonderful child's easel and we sat in lawn chairs and painted. That painting is right around the corner.

Anyway, this was a fertile period in my life. So many things were happening. I started with some childhood experience and now I'm talking about college experiences. They're all connected, of course.

RW: Right. Black Mountain must have been relatively new at that time.

SDeS: New, as an art school. Not so new as a local college. Only a few years before I went did it become a mecca, mainly for artists from New York. When I went there I studied with two artists without knowing anything about either of them, Ben Shahn and Robert Motherwell. Shahn was there for the first session, eight weeks, I think, and I had an incredibly good experience. Ben was a wonderful man. Talk about a mentor to take Gus Lugwig's place! We never met together as a class. It was only by appointment. We'd go to the door outside his studio, and everyone was in the same big studio-the plywood Bauhaus, I like to think of it. He'd see you when you wanted to see him. Great teaching!

You were on your own from the beginning. I'd come from New York where I had become fascinated by the subways. I think I rode every single subway line! And when I got to Black Mountain I could think of nothing but painting subways. Here I was in an oasis of the Appalachian Mountains painting subways for the summer! [laughs] I'd been filling this 12" x 18" notebook up with casein studies of subways. God, I wish I had that notebook! So I went to see Ben after a week and he praised my efforts. The second week, he praised the work again and then he said, "It's very interesting, but when are you going to make a painting?"

I didn't take it personally. Ben was challenging me. There was no store to go buy stretchers or canvas. I had to go by the woodshop and fashion some pieces of wood. I had to stretch my own canvas. You really had to work, in other words. I didn't see Ben again, until I got stymied. He looked at the work and praised it. In a sense, he praised it one time too many because I got it back to my studio and realized I couldn't touch it. It had been taken away from me by my teacher's praise.

I never learned that lesson myself. I was always inclined, as a teacher, to over-praise. But at any rate, I finished a second version of the subway. It's in the collection of the Princeton Art Museum, although they never show it.

Then the second session was totally different. This one was with Robert Motherwell, who wasn't, by any means, the name that he later became. He was young and was very cool. Ben Shahn was very intense and human, but Motherwell was kind of detached. He directed the class, just the opposite of Ben. He had us do scribble drawings for endless hours.

I never made that jump from representation to expressionism. I was floundering and clearly unhappy. Motherwell knew that. He asked me if I'd like to come over to his cottage and have a drink before dinner. I was kind of thrilled to be honored that way. And so I got to Motherwell's house and he offered me a martini. I'd never had a martini before! It went completely to my head, and while I'm in this euphoric state, Motherwell puts an avuncular arm on my shoulder. We're standing there in the living room and he says, "Steve, I notice you have a real gift with children. Have you considered a career in that field?" [laughs]

I was so numbed by the drink, I didn't know what he was saying until I got back to my room and it wore off. Then I realized what he was telling me! I was so angry and hurt, just furious, really. By the morning of the next day, I'd packed my bag and left. I got the Greyhound bus and went over the Appalachians to southern Indiana and holed up at the family farm. It shows how hair-trigger, thin-skinned I was. But that was my indication from then on how not to teach [laughs].

RW: Okay. Now earlier you said that becoming an artist was a precarious transition. And you said you almost applied for graduate school in the department of religious studies at Princeton. Of course, I think of your angels. They seem to speak to a poetic, religious aspect of meaning through art. So your path maybe didn't really turn away from some of those interests. Do you see where I'm going with this?

SDeS: Well, poetry is one of the great creations of the human spirit and mind. It gets categorized and isn't brought into growing ritual use. Or maybe it is and I just don't know it.

I had the experience of singing for a year in a chapel choir in college. We sang almost exclusively Renaissance church music. It was incredibly powerful. The good Renaissance music surpasses so much of the more refined and developed music that came later.

When I was in the army stationed in Germany, I asked a Lutheran cantor whether I could sing in the choir. He said, yes, of course. We sang Bach's B Minor Mass at Easter. I didn't know how beautiful that was until several years ago when my wife and I were in Paris on a fellowship. We went to hear the B Minor Mass in a Gothic church in Paris. It is the most powerful piece ever to come along!

Well, this all probably has more to do with making art than anything else. It's things like this, fragments here, experiences that don't seem to connect until you get some space and time between you.

I had another wonderful experience in Germany. I got to know a bunch of German teenagers who were coming to America House and I got this idea of having a puppet group. And right away, I discovered the greatest theme for the puppets: Max and Moritz. Every kid in Germany knows Max and Moritz, the original Katzenjammer Kids. They were trouble-makers, funny and actually with a lot of malicious, almost sadistic, humor. But that's another thing. At any rate, I got together about 12 of the teenagers and we would make puppets in the interrogation room of the military intelligence building. [laughs]

RW: All this was while you were in the service?

SDeS: Yes. I made puppets! The kids just naturally took to the right characters. One of the girls was named Edeltrude. She had a pie face and that was like Max. So we gave an incredible puppet performance! All around town were these red posters saying Puppenteater-Max und Moritz.

We gave three performances that afternoon. The little kids were totally immersed in this drama going on behind the little stage. They would go up and get as close as possible.

From that experience, I thought that I'd like to work with children, maybe in a more serious way. I'd been introduced to the idea of working with Bruno Bettelheim in Chicago where he had the Orthogenic School, this very avant-garde treatment center for autistic children. I wrote him a letter from Germany and asked if I could join his group. He said, "Yes, come and see me." So when I got out of the army, I found myself driving to Chicago in a blizzard. Well, Bettelheim was the most intimidating man, face to face, that I'd ever met. He was just bristling with energy. He told me that there was no way he could show me around because it was near Christmas and all the family neuroses would be stirred up. I knew, even before I got out the door, that I couldn't work with him. Instead, I took a job as a group leader at Union Settlement House in East Harlem, Manhattan.

RW: Group leader, meaning...?

SDeS: I had two groups of boys, all Puerto Rican. My younger group, the twelve-year-olds were called the Red Eagles. The older group was called the Cavaliers. I inherited these names.

RW: It wasn't a therapy group?

SDeS: No. I was just a co-player. I had some great tests that I didn't realize were tests. We were on East 104th Street about four blocks from Central Park. When we went on our first junket with the Red Eagles, as soon as they got on the grass, they all ran in different directions and ditched me. I just ran after each one of them and bagged them, pffft. Boy that did it! Because I could catch them [laughs].

RW: You're in. That was your basketball.

SDeS: Yes. I wasn't in great shape, but I could still run.

RW: Now this was after getting out of the army?

SDeS: Right. Going into the army was one of the wildest, unthought-out acts I ever made in my life. I found myself in the midst of the real America, and it turned out to be fantastic! I got the GI bill, just from a practical point of view. Had I not been sent to Germany I would never have had that puppet experience. But when I got out of the army, I didn't really know what to do with myself. So I wrote Princeton and asked if I could do graduate study with them. I wrote primarily to Professor George Thomas, who I mentioned before. Almost immediately I got back this glowing letter. They offered a scholarship. So I was just on the verge of deciding to take them up on it and I met my future wife and fell in love. I was in Southern California at that time. I hadn't been rehired by the Chadwick School in Rolling Hills where I'd found a job teaching. My wife to be was going north to Los Altos to take a kindergarten teaching job and I thought, why don't I go along with her instead? That's what got me to Berkeley. And traveling north to the Bay Area, after trying this social route of being a teacher and group leader, I thought I'd better make some good use of this time. I decided to get a teaching credential, and I got it! I did the whole thing at Cal and ended up never using it, as a matter of fact.

RW: So now I want to get back to your angels, if you would.

SDeS: Well, I never systematically tried to parse it out. At the heart of it, and without trying to beat around the bush, I think it had quite a bit to do with my mother's death in an airplane crash. What it boils down to, at some deep psychological level, is you try to change that. You can't, but you try in your imagination. The angel is the vehicle to saving her life. I had a dream, oh, I haven't thought about it in years! I was coming across the Bay Bridge in the afternoon light and was just approaching the tunnel in Yerba Buena Island. I'm in a car, and-the dream eludes memory-I saved my mother by holding an airplane up that was going to crash in the tunnel. It was at a point of no return, and I guided it safely through. I think that's kind of a prototype of much of my imaginary thinking and feeling.

I wrote a poem that kind of expresses this. I was a freshman in college, and I was standing at the window of my dorm. I'm looking down. I'm scared. I've got reports and readings to do, and I'm very ill at ease. So I'm standing and looking through the neo-Gothic tracery of my window on the third floor and looking down. I see all the students, all the traffic: students, bicycles, cars. Somehow I focus on the figure of a student walking briskly on one path. And, at right angles, on another path a boy is riding a bicycle. The two intersect in a perfect cross. And out of all this angst I was feeling, suddenly I was left with a great sense of tranquility. I was at peace. I can only make certain assumptions that the power of the cross does stem from this intersection of the vertical and the horizontal. It was one of the formative experiences.

The poem goes something like this:

How many times in life

Would we rather have wings than arms?

To float, to soar, to fly is to be.

To have arms is only to do.

I think it ties to my experience at the window in the dorm. I think what gave me peace of mind was the realization that you can exist on two planes, the plane of accomplishment and the plane of the spirit-where you need nothing but being to affirm being alive.

RW: It strikes me that your work evokes something ancient, like ancient artifacts. It seems almost archeological.

SDeS: Yes. I welcome that response. It's more satisfying to me to have a sculpture be puzzling rather than explanatory. Early on, working with Pete, I saw the beauty of events in the clay that were not foretold, that just happened. I saw that these events were more meaningful and more powerful than ones described by the marks that the hand leaves. It's not a common goal, but early on, I came to love the ambivalent and the unannounced imagery.

RW: The figures in your work are fragmented-the fragmented figure. That's such a major part of your work it seems. Could you say something about that?

SDeS: Oh, yes. A totally complete image leaves little for the viewer. One attraction of archeological digs is that it can lead, to varying degrees, to vast unspoken imagery that calls to the mind of the viewer--if the viewer is active. It's more satisfying than elements that are spelled out too explicitly. That's true in poetry, too. So much is left out, leaving vast room for the reader to join in.

RW: I wonder if there's another thing about the fragmented figure? Could it be a way of conveying that we are not really complete, or that our knowledge of ourselves is not complete?

SDeS: Yes. We don't have a sense of wholeness in life, a sense of our connection with nature. Our lives are usually cobbled together. It reminds me of something Hemingway said about writing, that most writers go to their worktables like carpenters who get to a job site and use whatever they have at hand to cobble something together. I think our lives are something like that.

RW: Yes. I was thinking about some of your work that went up to the Napa Valley Museum recently, the columns, a lot of which you've assembled from fragments that have accumulated in your studio over a period of years. It's like these figures or columns seem to be in some unfinished process that's on its way to something. You could think about them that way, and I think the same thing applies to a lot of your work. But just as easily, one could think, here's a figure that's falling apart and it's on its way to returning to the earth. You could see a lot of your work either way, it seems to me.

SDeS: Yes. I cherish that! It gives up the illusion that we're going to master things for very long. Any person with consciousness has to know we are here between being born and dying. We were born out of eternity and we return to a state of eternity. Wanting more from life than a glimpse is just to lose balance between existing and non-existing. But how to put that into form has been the challenge.

This article originally appeared in Works & Conversations and is republished with permission. Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of Works & Conversations, an inspiring collection of in-depth interviews with artists from all walks of life, and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

2 Past Reflections

On Aug 10, 2015 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Thank you for another Wonderful interview and one that made a deep impact on me. Here's for realizing how our bodies can impact our creative works (whatever form they may be) and here's to cobbling together a life out of all the fragments around us. Brilliant!

On Aug 15, 2015 Mike Hansel wrote:

I found this article, incredbly inspiring. I'm sure you will to. It's brief and to the point. Check it out. http://worldobserveronline....

2 replies: Clementine, Ry | Post Your Reply