Emerson on Small Mercies, the True Measure of Wisdom, and How to Live with Maximum Aliveness

“To finish the moment, to find the journey’s end in every step of the road, to live the greatest number of good hours, is wisdom.”

In contemplating the shortness of life, Seneca considered what it takes to live wide rather than long. Over the two millennia between his age and ours — one in which, caught in the cult of productivity, we continually forget that “how we spend our days is … how we spend our lives” — we’ve continued to tussle with the eternal question of how to fill life with more aliveness. And in a world awash with information but increasingly vacant of wisdom, navigating the maze of the human experience in the hope of arriving at happiness is proving more and more disorienting.

How to orient ourselves toward buoyant aliveness is what Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803–April 27, 1882) examines in a beautiful essay titled “Experience,” found in his Essays and Lectures (public library; free download) — that bible of timeless wisdom that gave us Emerson on the two pillars of friendship and the key to personal growth.

Emerson writes:

We live amid surfaces, and the true art of life is to skate well on them… To finish the moment, to find the journey’s end in every step of the road, to live the greatest number of good hours, is wisdom. It is not the part of men, but of fanatics … to say that the shortness of life considered, it is not worth caring whether for so short a duration we were sprawling in want or sitting high. Since our office is with moments, let us husband them. Five minutes of today are worth as much to me as five minutes in the next millennium. Let us be poised, and wise, and our own, today. Let us treat the men and women well; treat them as if they were real; perhaps they are… Without any shadow of doubt, amidst this vertigo of shows and politics, I settle myself ever the firmer in the creed that we should not postpone and refer and wish, but do broad justice where we are, by whomsoever we deal with, accepting our actual companions and circumstances, however humble or odious as the mystic officials to whom the universe has delegated its whole pleasure for us. If these are mean and malignant, their contentment, which is the last victory of justice, is a more satisfying echo to the heart than the voice of poets and the casual sympathy of admirable persons.

Indeed, Emerson highlights the practice of kindness as a centerpiece of the full life, suggesting that our cynicism about the character and potential of others — much like our broader cynicism about the world — reflects not the true measure of their merit but the failure of our own imagination in appreciating their singular gifts:

I think that however a thoughtful man may suffer from the defects and absurdities of his company, he cannot without affectation deny to any set of men and women a sensibility to extraordinary merit. The coarse and frivolous have an instinct of superiority, if they have not a sympathy, and honor it in their blind capricious way with sincere homage.

An equally toxic counterpart to such self-righteousness, Emerson argues, is our propensity for entitlement, which he contrasts with the disposition of humility and gratefulness:

I am thankful for small mercies. I compared notes with one of my friends who expects everything of the universe and is disappointed when anything is less than the best, and I found that I begin at the other extreme, expecting nothing, and am always full of thanks for moderate goods.

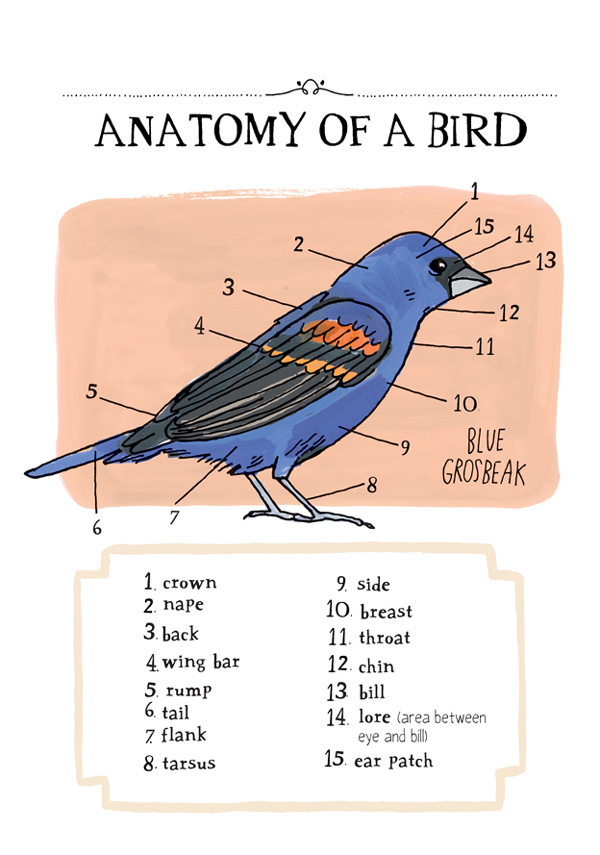

Illustration by Julia Rothman from 'Nature Anatomy.

In a sentiment almost Buddhist in its attitude of accepting life exactly as it unfolds, and one that calls to mind his friend and Concord neighbor Thoreau’ssuperb definition of success, Emerson bows before the spiritual rewards of this disposition of gratefulness unburdened by fixation:

In the morning I awake and find the old world, wife, babes, and mother, Concord and Boston, the dear old spiritual world and even the dear old devil not far off. If we will take the good we find, asking no questions, we shall have heaping measures. The great gifts are not got by analysis. Everything good is on the highway. The middle region of our being is the temperate zone. We may climb into the thin and cold realm of pure geometry and lifeless science, or sink into that of sensation. Between these extremes is the equator of life, of thought, of spirit, of poetry, — a narrow belt.

Only by surrendering to life’s uncontrollable and unknowable unfolding graces — or what Thoreau extolled as the gift of “useful ignorance” — can we begin to blossom into our true potentiality:

The art of life has a pudency, and will not be exposed. Every man is an impossibility until he is born; every thing impossible until we see a success.

Or, as a modern-day wise woman admonished in one of the greatest commencement addresses of all time, it pays not to “determine what [is] impossible before it [is] possible.”

A century and a half before Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert illuminated how our present illusions hinder the happiness of our future selves, Emerson adds:

The results of life are uncalculated and uncalculable. The years teach much which the days never know… The individual is always mistaken. It turns out somewhat new and very unlike what he promised himself.

This article originally appeared in Brain Pickings and is republished with permission. The author, Maria Popova, is a cultural curator and curious mind at large, who also writes for Wired UK, The Atlantic and Design Observer, and is the founder and editor in chief of Brain Pickings.

On Aug 3, 2015 infishhelp wrote:

Letting go of old hooks and keeping out of new hooks are two different things when playing the useful ignorance game. Rest assured that our ignorance will be used, but by whom and for what purpose?

Post Your Reply