Can Compassion Change the World?

Daniel Goleman talks with Greater Good about his new book, A Force for Good: The Dalai Lama's Vision for Our World.

The Dalai Lama has a long history of meeting and collaborating with social scientists—psychologists, neuroscientists, economists, and others looking to understand the science of human emotions and behavior. Through these collaborations, he has learned about the research in this area and has encouraged scientists to pursue fields of inquiry more directly aimed at serving the public good.

Now that he will be turning 80 this year, the Dalai Lama asked psychologist and bestselling author Daniel Goleman to write a book outlining his vision for a better world and the role science can play. The result of their collaboration, A Force for Good: The Dalai Lama’s Vision for Our World, is both a translation of the Dalai Lama’s ideals and a call to action.

Recently, I spoke with Goleman about the book.

Jill Suttie: After reading your book, it seemed to me that the Dalai Lama’s vision for a better future comes down, in large part, to cultivating compassion for others. Why is compassion so important?

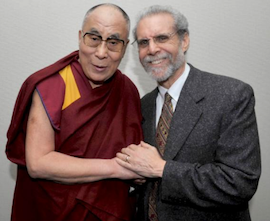

The Dalai Lama and Daniel Goleman

Daniel Goleman: He’s not speaking from a Buddhist perspective; he’s actually speaking from a scientific perspective. He’s using scientific evidence coming from places like Stanford, Emory, and the University of Wisconsin—also, Tanya Singer’s project at the Max Planck Institute—which shows that people have the ability to cultivate compassion.

This research is very encouraging, because scientists are not only using brain imagery to identify the specific brain circuitry that controls compassion, but also showing that the circuitry becomes strengthened, and people become more altruistic and willing to help out other people, if they learn to cultivate compassion—for example, by doing traditional meditation practices of loving kindness. This is so encouraging, because it’s a fundamental imperative that we need compassion as our moral rudder.

JS: You use the term “muscular compassion” in your book. What do you mean by that?

DG: Compassion is not just some Sunday school niceness; it’s important for attacking social issues—things like corruption and collusion in business, government, and throughout the public sphere. It’s important for looking at economics, to see if there is a way to make it more caring and not just about greed, or to create economic policies that decrease the gap between the rich and the poor. These are moral issues that require compassion.

JS: Compassion can be cultivated through mindful meditation. But, I think a lot of people start meditating for personal reasons—to decrease stress and to learn to be more accepting of what is. How does that lead to social activism?

DG: I don’t agree with that interpretation of what meditation or spiritual practice is for. That view of mindfulness leaves out the traditional coupling of mindfulness with a concern for other people—loving kindness practice, compassion practice. I think the Dalai Lama’s view is that that’s inadequate. Meditation does not mean the passive acceptance of social injustice; it means cultivating the attitude that I care about other people, I care about people being victimized, and I’ll do whatever I can to help them. That he sees as true compassion in action.

JS: Is there any research that supports the idea that mindfulness and social activism are linked?

DG: There’s some evidence that mindfulness not only calms you and gives you more clarity, but it also makes you more responsive to people in distress. In one study, where people were given the chance to help someone in need—offering a seat to someone on crutches—mindfulness increased the number of people who did that. And, if you extrapolate from there to helping the needy whenever they cross your radar in any way you can, it suggests that mindfulness would help. However, there’s even more direct evidence that cultivating compassion and loving kindness enhances the likelihood of helping someone. Putting the two together is powerful.

JS: In your book, the Dalai Lama refers to something he calls “emotional hygiene”—or learning how to handle difficult emotions with more skill and equanimity. He says it should be as important as physical hygiene, and that we should all improve our “emotional hygiene” before trying to tackle social problems. Why is that?

DG: That’s the Dalai Lama’s perspective—we need to get all of our destructive and disturbing emotions under control before we act in the world. If not, if we act from those emotions, we’ll only create more harm. But if we can manage our distressing emotions in advance, and have calm, clarity, and compassion as we act, then we’ll act for the good, no matter what we do.

It’s not that any one emotion is destructive, though; it’s the extremes that can harm others and ourselves. When emotions become destructive, you need to manage them and not let them run you. For example, anger: if it mobilizes you and energizes you and focuses you to right social wrongs, then it’s a useful motivation. However, if you let it take over and you become enraged and filled with hatred, those are destructive, and you’ll end up causing a lot more damage than good.

JS: I think it’s difficult for some people to actually know when their emotions are causing them to act inappropriately, though.

DG: That’s why self-awareness is absolutely crucial. Many people get hijacked by their emotions and have no idea, because they are oblivious, because they lack self-awareness. And what meditation and mindfulness practice can do is to boost your self-awareness so you can make these distinctions more accurately, with more clarity.

JS: One of the Dalai Lama’s tenets you articulate in the book is that we should have a universal ethic of compassion for all. Does he suggest we extend compassion even to those who commit atrocities, like murder or genocide?

DG: He holds out an ideal of universal compassion, without exception. That’s something we can move toward. But he also gives us a very useful instruction: He says, make a distinction between the actor and the act. Oppose the evil act—no question—but hold out the possibility that people can change. That’s why he opposes the death penalty, because a person can turn their life around, and we shouldn’t exclude that possibility.

Universal compassion is a high standard, and I don’t think most of us can meet it. But we can move toward it by expanding our circle of caring. Paul Ekman has had extensive dialogues with the Dalai Lama about this, and he says that this is a good target, but that it’s very hard to reach. It goes against natural mechanisms that make us favor our own group—our family, our company, our ethnic group, etc. So, the first step is to overcome that tendency and to become more accepting of and caring toward a wider circle of people. Caring for everyone is the final step, and I don’t think many people can get there. But we can all take a step closer.

JS: It sounds like many of the Dalai Lama’s suggestions are aspirational in nature.

DG: The Dalai Lama often talks to people with great aspirations, and, after he’s gotten them all roused up, he says, “Don’t just talk about it, do something.” That’s part of the message in my book: Everyone has something they can do. Whatever means you have to make the world a better place, you need to do it. Even if we won’t see the fruits of this in our lifetime, start now.

This article is printed here with permission from the Greater Good Science Center (GGSC). Based at UC Berkeley, the GGSC studies the psychology, sociology, and neuroscience of well-being, and teaches skills that foster a thriving, resilient, and compassionate society. You can learn more about the science and power of gratitude at the Greater Good Gratitude Summit.

Jill Suttie, Psy.D., is Greater Good‘s book review editor and a frequent contributor to the magazine.

On Jul 9, 2015 mack paul wrote:

I had so much trouble with stress from my teaching job that I was constantly ill. I unsuccessfully tried to avoid stress and I would get really angry with kids because I thought they were causing my stress. It was actually me causing me stress.

I've learned over the past 25 years since that I am really not at all separate from other people. Our well being is intimately connected. I do all I can to help other people out of naked self interest.

Post Your Reply