Six Promising Trends for the New Nature Movement

Several years ago, Minneapolis’s Washburn Center for Children, provider of mental health services to about 2,700 youths each year, decided a new facility was needed to replace the old building. This morning, the business journal Finance & Commerce reported on the Center’s coming Grand Opening — and on Washburn’s pioneering idea.

.jpg)

“One of the keys to treating … children is connecting them with nature…” wrote Brian Johnson. “Large windows, abundant natural light…curved hallways, high ceilings, extensive landscaping and strong ties to the outdoors jump out at visitors… On the outside, a large playground with grass, climbing equipment, a basketball court and trails will replace the old building’s undersized asphalt play area.” The healing power of nature is literally woven into the structure of the place.

Architect Mohammed Lawal (a C&NN board member ) designed the new center. And former C&NN chair Marti Erickson, Minnesota media icon Don Shelby and Washburn’s CEO Steve Lepinski, among many other leaders and contributors, helped make it happen.

Not every potential biophilic feature was adopted, but the opening of the new Washburn Center is indicative of the kind of progress that we’ve seen in recent years on many fronts.

As impatient as many of us feel, the children and nature movement — or, by a broader name, the New Nature Movement, which includes adults — is having an impact, especially in these six arenas:

1. Increased research on the link between our experience of the natural world and human health and cognition.

After decades of inadequate funding and attention, researchers have made strides in understanding the impact of nature experience or the lack of them on several elements of human development, including affecting production of the stress hormone cortisol (related to violence).

Among other advances in research, we see a recent and critical shift in thinking about child obesity: Some obesity experts, while acknowledging the crucial role of nutrition, are now paying additional attention to what they call the “pandemic of inactivity.”

New research also describes the pernicious impact of sitting long hours every day, which may stimulate some of the same diseases as smoking — even if the sitters are not overweight: sitting is the new smoking. These are only a few samples of the impressive flow of new research now making the overdue transition from correlative to causative.

New research also describes the pernicious impact of sitting long hours every day, which may stimulate some of the same diseases as smoking — even if the sitters are not overweight: sitting is the new smoking. These are only a few samples of the impressive flow of new research now making the overdue transition from correlative to causative.

2. Greater understanding that, in cities, the quality of nearby nature is linked to human well-being and biodiversity.

There’s more than one reason to create a park or preserve open space. Urban parks with the greatest variety of species are the ones with the best impact on human psychological health.

As the new Washburn Center suggests, biophilic design (the creation of living buildings through the addition of green roofs, hanging gardens, abundant natural light and many other features) is beginning to enter the vernacular of mainstream architects, urban planners, health officials, educators and business people. Biophilically-designed workplaces and schools are seeing an increase in productivity and decrease of sick days taken. Across the country, some libraries are assuming a new role as connectors of people to nearby nature and centers of bioregional knowledge.

In recent months, The National League of Cities – an organization that supports leaders in 19,000 municipalities across the U.S. – has taken a leadership position on this issue, and NLC and C&NN will soon announce a major initiative to connect children and families to nature.

3. More health care professionals are getting involved.

A growing number of pediatricians believe that nature experiences should be recommended or prescribed. Physicians such as Washington D.C.’s Dr. Robert Zarr, Austin’s Dr. Stephen Pont, and Great Bend’s Dr. Mary Brown are going beyond individual prescriptions to organizing health care systems — encouraging Vitamin N for both prevention and therapy. Zarr built a database of available green areas in Washington D.C., and has organized physicians who use it to advise the families they see.

Many public health experts are promoting nearby nature. Pediatric occupational therapists are also taking notice. Angela Hanscom, a leader in her field, she views time spent in nature as “the ultimate sensory experience for all children and a necessary form of prevention for sensory dysfunction…The more we restrict children’s movement and separate children from nature, the more sensory disorganization we see.” The fields of ecopsychology and nature therapy are also expanding.

4. More educators are promoting the benefits of nature-enriched schools.

Despite increased dominance of technology in every aspect of our lives, there is a counter-trend: growing unease about the impact of tech immersion on children, and greater awareness of the need to balance digital skills with the development of the senses and cognitive abilities stimulated by more time connected to nature and other direct experiences.

As yet, this counter-trend does not have a powerful lobby. But we do see apparent increases in the number of nature preschools, natural school yards and gardens. Independent primary and secondary schools are particularly interested, but public education is tentatively adopting some of the methods, as well.

As yet, this counter-trend does not have a powerful lobby. But we do see apparent increases in the number of nature preschools, natural school yards and gardens. Independent primary and secondary schools are particularly interested, but public education is tentatively adopting some of the methods, as well.

Now comes word of new research suggesting the educational power of greening schools on standardized test scores.

“Exposure to nature has long been linked to lower stress levels and mental alertness, but a new, first-of-its-kind study finds it is also associated with higher scores on a standardized test,” reports Pacific Standard magazine. “Even after controlling for factors such as race and parental income, Massachusetts third-graders with greater ‘exposure to greenness show better academic performance in both English and math,’ reports a research team led by Chih-Da Wu of National Chiayi University in Taiwan.

At the University of Illinois, a yet-to-be published ten-year study of over 500 Chicago schools finds similarly stunning results for standardized testing in schools that incorporate more nature. The results seem to be best for students with the greatest need.

5. The movement is expanding from both the grassroots and the political canopy.

We see a steady increase of the number of families that have banded together to create family nature clubs. Approximately 120 regional, state and provincial grassroots campaigns have emerged in North America, bringing together unlikely partners — conservatives and liberals, conservationists and developers, educators and physicians — united in their determination to connect future generations to the natural world. Millennials are helping lead the way, through such efforts as C&NN’s Natural Leaders Network.

Large institutions and sectors such as the U.S. Department of the Interior, conservation organizations, business interests such as the outdoor industry, and health organizations are taking action. Other, similar movements, such as the drive for local food production, are also stimulating interest in connecting families to nearby nature.

6. The movement is increasingly international, spreading the idea that children have a human right to the benefits of the natural world.

The “movement” comes from no one country, culture, profession, organization or economic group. Its core ideas are not new; they predate by decades or longer the current but fragile wave of public awareness. The U.S. has much to learn from the research, innovation and traditional practices beyond its borders. Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the UK, The Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, and many other countries continue to move quickly on these fronts.

In 2012, World Congress of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), attended by more than 10,000 people representing the governments of 150 nations, as well as more than 1,000 non-governmental organizations, passed a resolution declaring that children have a human right to experience the natural world and a healthy environment. The Child’s Right to Connect with Nature and to a Healthy Environment calls on IUCN’s membership to promote the inclusion of this right within the framework of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (signed but still unratified by the United States). There are no borders to this human right, and no borders to the responsibilities that come with it.

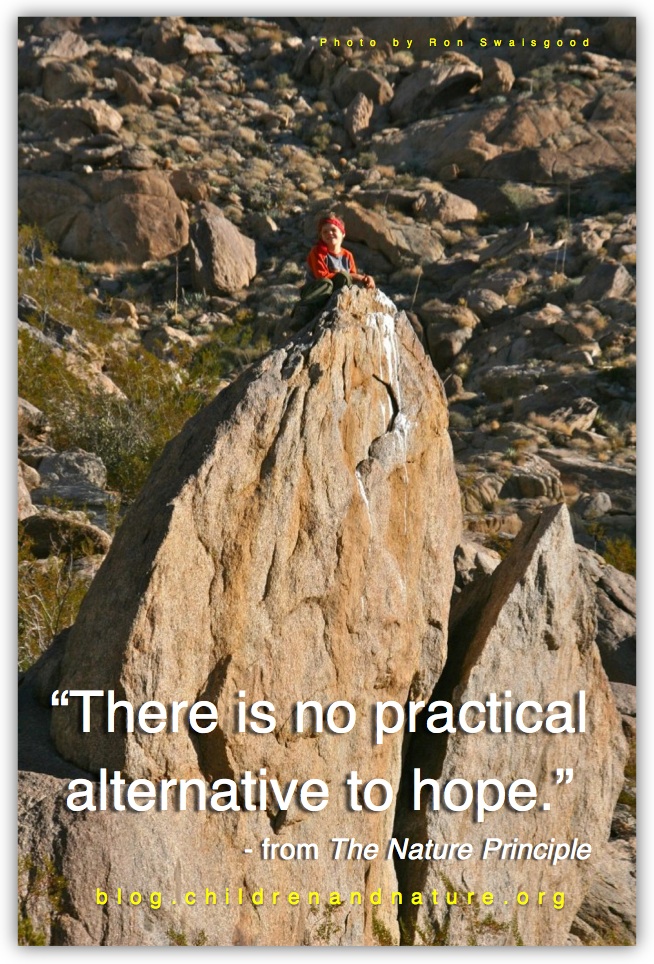

Given the powerful economic drivers that are moving people away from nature, the obstacles may at times seem insurmountable. We see advances and we see setbacks. But history has shown that social action can win if enough people join a cause – and if they can imagine what success looks like. In the end, there is no practical alternative to hope.

This article originally appeared on Children & Nature Network's blog and is republished here with permission. The author, Richard Louv is Co-Founder and Chairman Emeritus of the Children & Nature Network, an organization supporting the international movement to connect children, their families and their communities to the natural world. He is the author of eight books, including "Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder" and "The Nature Principle." In 2008, he was awarded the Audubon Medal.

On Jan 12, 2015 Eileen Keyes wrote:

Interesting that "researchers" are now making this connection. It has always been so obvious to me. When I was in college, I wrote a term paper for Intro to Education class, on the importance of integrating nature into childhood education. That was in 1974. The prof happened to be also a elementary school principal. He took me seriously and added a one hour weekly nature walk for third grade level. I was thrilled, though I saw it as inadequate. I realize he had to start at that level. I've always wondered how it panned out.

1 reply: Kristin | Post Your Reply