An Abiding Ocean of Love : A Conversation with Chris Jordan

The internationally acclaimed artist and cultural activist Chris Jordan, a featured speaker at the Center for Ecoliteracy's June 2013 seminar "Becoming Ecoliterate," explores contemporary mass culture and asks us to consider our roles in becoming more conscious stewards of the world.

He spoke with Lisa Bennett, the Center's director of communications and coauthor of Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating Emotional, Social, and Ecological Intelligence. They discussed how Jordan's work reflects two of the five ecoliterate practices described in the book: making the invisible visible and developing empathy for all living things.

LISA BENNETT: My son recently saw a sign that said that it takes five years for a milk carton to decompose and said he couldn't understand what difference that made. It's a notion that underlies many of our everyday behaviors. But what you do, especially in your series "Running the Numbers," is create beautiful works of art that reveal just what happens when 300 million of us do some seemingly innocuous thing, like throw out a milk carton or cell phone or water bottle. What prompted you to use art to make the invisible visible?

"Cell phones #2," Atlanta 2005. 44" x 90." From Intolerable Beauty: Portraits of American Mass Consumption.

CHRIS JORDAN: As your son pointed out, one carton doesn't make much difference. It is only in the aggregate that it matters, and it is turning out to matter more than any of us imagined. Yet there is nowhere we can go to see these cumulative effects of our individual actions — and especially nowhere we can go to see the 30 billion tons of carbon emitted last year. The only information we have are the statistics: "hundreds of millions," "billions," and now "trillions." And if that is the only information we have to try to comprehend and feel something about the profoundly important phenomena threatening our world, then that's a huge problem.

"Gyre," 2009. 8 feet x 12 feet, in 3 panels. From Running the Numbers II: Portraits of Global Mass Culture. Depicts 2.4 million pieces of plastic, equal to the estimated number of pounds of plastic pollution that enter the world's oceans every hour. All of the plastic in this image was collected from the Pacific Ocean. Top: the full artwork. Bottom: detail.

As a photographer, I wanted to go to the place where all our garbage ends up. I wanted to stand in front of the Mount Everest of trash and take photos. But of course, there is no such place. The best I could ever do was to get one drop in the river of our trash. I vividly remember photographing a two-story-high pile of garbage in Seattle. A giant machine came, picked up the entire pile, and put it into a rail car. I asked the guy, "Where is that train going?" It turned out that a mile-long train of garbage runs out of Seattle every day, and all we could see was one drop in that river. That was the genesis of my desire to illustrate these otherwise incomprehensible effects.

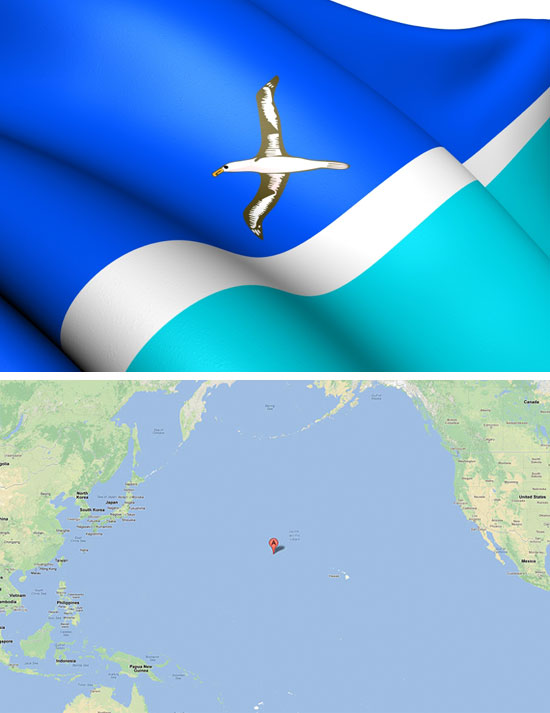

Top: the "unofficial flag" of the Midway Islands, featuring an albatross. Bottom: the location of Midway Atoll.

LB: More recently, your work has taken you to Midway Island — 2,500 miles from any other body of land — to study and photograph the albatross. Why that place and those birds?

CJ: I was always a little dissatisfied with my "Running the Numbers" work because what I really want to do is help people like your son understand that these global issues are personal to each one of us. I wanted to create a bridge between the global and the personal. My "Running the Numbers" work is inherently abstract, conceptual art. It points in the right direction, but what I'm really interested in is feeling. That's the power of art. It reminds you how you feel about something.

2009. From Midway: Message from the Gyre.

More specifically, I had been working on a piece about plastic and ocean pollution. I was at a meeting with a bunch of scientists and said I wanted to take pictures of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch [the place known for its high concentrations of plastics and other debris trapped by the currents in the North Pacific]. A young activist named Anna Cummins turned to me and said, "If you want to see what's happening, go look inside the stomach of a baby albatross at Midway Island." And as I began researching it, it became more evident that an impossibly coincidental epic fable was happening on this island.

Imagine if you and I were filmmakers, and we had a $100 million budget to make the most powerful film possible about pollution. Think about where would be the most profound, horrific, multilayered, metaphoric place of anywhere on Earth that our plastic could be showing up. What about inside the cutest, softest, gentlest, most vulnerable of all animals? It would have to be baby birds — trash inside the stomachs of baby birds. Oh my god, genius!!!

Where should that be happening? Staten Island? Kentucky? Where would the most symbolic possible place be? The most remote spot on the planet. So get a globe, and look and see: the Pacific is the biggest ocean. Put your finger in the middle of that ocean. How about a little island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean? Now what bird? It should be white, because white symbolizes peace and vulnerability. Then look through a list of what would be the most symbolic bird as "messenger." Oh, the albatross, of course! Then the last thing: What should we name this island? Coconut Island? Coral Atoll? What would be most symbolic of where humans find ourselves now — between the collapse of the old and the new not yet emerging, making choices that affect life on Earth? How about "Midway"? What more provocative term could there possibly be?

As I went there, the other piece that was so astonishing was that the albatross is an incredibly magnificent, sentient being. Their eyes, like those of eagles, are piercing and gorgeous. They're huge and stunningly graceful, elegant creatures. They've been living on Midway for four million years and never had a predator. So they know no fear. You can walk right up and get so close that if they wanted to, they could peck at your face with their beaks. I got to witness and film babies hatching. And as I went and witnessed this, I realized there was an environmental tragedy happening there, and it was wrapped up in this envelope of exquisite beauty and joy and grace.

LB: Your images of the baby birds are heartbreaking, though. What impact have you seen them have on children?

CJ: That might be the most inspiring part of the whole process for me. I learned that when you present the truth of our world, even to second graders, and you don't carry judgments, wag fingers at them, or tell them how they should feel or behave, then it has incredible effects. The challenge is that it's powerful medicine. It can take you down the hellhole into grief and despair and bottomless hopelessness, or it can be a transformative experience, depending on the container in which it is held. I've been really fortunate to work with a lot of teachers who show my work to their kids and do it wisely and with intention. They talk about who is feeling something.

LB: When we visited years ago, you spoke about an encounter with the writer Terry Tempest Williams. You asked her to write an essay to accompany your Midway photographs — something that would help get people get from tragedy to hope — and she declined, sending you back, instead, to Midway. Why?

CJ: From the beginning of the project, I was deeply inspired by Terry's work. From her book Refuge, I took the concept of witnessing. To get to the other side, we have to walk all the way through the fire. I thought that was what I had done the first time at Midway. I came back emotionally and spiritually devastated. But I was confused by it, and I was especially confused and heartbroken by the responses of people who wrote saying they saw the images and felt paralyzed, or panicked. That's when I contacted Terry. She looked at my portfolio of prints and said, "I'm sorry I can't get you to hope from here. I think there is more to the story. You haven't gone all the way through the fire yet." It was an amazing insight, because she had never been there. She just had this intuition that there was something more.

Still from trailer of Chris Jordan's upcoming film, Midway: Message from the Gyre.

I decided that I had to go back, and it was a stunning experience. The first time, we had never seen a live albatross; in the fall, all albatross are off the island. We had only seen one facet of their life cycle, the tragedy of tens of thousands dead on the ground. It was an exquisitely beautiful experience to arrive a second time and meet a million of these stunning creatures, as thick as people at an outdoor concert. And as I returned again and again, I was able to see them at different stages of their life cycle — doing mating dances, hatching from eggs — and to film with an incredible level of intimacy you just don't see in wildlife films. Typically I'd look at them from three inches away. The experience began to evolve from witnessing tragedy to falling in love, and the tragedy began to be wrapped in this envelope of grace and elegance and beauty. That was the bigger story.

LB: On a more recent trip, you held the remains of a baby bird and had a profound experience of grief. What happened?

CJ: That was a moment when I accidentally killed a healthy albatross myself. There were so many on the ground, and I ran over one with my bike. I jumped off and immediately got down and looked at her; she was gasping and choking up a bunch of orange liquid. She tried to move, and I saw that both her wings were broken. I think my bike had passed right over her body, and she suffered internal injuries. She took four days to die. I visited her over and over. It was an astonishing experience to discover how much it impacted me that I had inadvertently taken the life of this beautiful, innocent creature. I felt a depth of grief I never thought I had in me, for one bird on one island I never thought I would visit. I discovered that I had this tremendous amount of grief over this one little life I had taken, but there was really nothing more beautiful or lovable about that one bird than any of the other albatross on the island. I discovered that somewhere hidden in my heart, I must have that much love for every one of them.

Then I thought that this creature is not more magnificent than whales or gorillas or tigers, or people for that matter. And I had this intuitive experience that my Buddhist friends talk about — discovering my love for all beings. That to me is the teaching of grief. I came to discover that grief is not sadness. Grief is love. Grief is a felt experience of love for something lost or that we are losing. That is an incredibly powerful doorway. I think we all carry that abiding ocean of love for the miracle of our world. And if, on a collective level, we could grieve together and rediscover that deeper part of our collective psyche, then healing the symptoms of that disconnect could happen much faster than we imagine.

LB: Your work, which began with making the invisible visible, has progressed to a place of developing tremendous empathy for all of life. Do you think that there is a connection between making the invisible visible and empathy?

CJ: I sure do. Our connection with the world is our feelings. If we see something happen, but have no feeling for it, there's no connection. If we do have a feeling, whether it's anger or rage or grief or whatever, we're connected to that thing. And in order to feel what is going on, we have to comprehend it.

LB: Still, many people fear opening up to the seriousness of the ecological crises we now face. What do you think can help us overcome that?

CJ: One powerful elixir is beauty. There is nothing quite like beauty. When you bring beauty and grief together, you can't look at it, because it's so sad — and you can't look away, because it's so beautiful. It's a moment of being transfixed, and the key is turned in the lock.

LB: Does that mean you have gotten to the place of hope you were looking for?

CJ: I'm not big on hope now. Joanna Macy has said that hope and hopelessness live on a continuum of disempowered mind states. When there is hope, we're hoping something outside our own agency will work in our favor. We hope to live to an old age. My son Emerson likes to joke that he hopes he does his homework, and this illustrates the disempowered mind state of hope. Joanna says the opposite of hope is not hopelessness; it's action. That's the genius of Dante's Inferno. As Dante walks into the fire, the gates say, "Abandon hope, all ye who enter here." The idea is to let go of the passive victim role of hope and take control of one's own destiny. As a culture, we have our compass set to "hope." But it's a giant puff of smoke, with nothing there. Culturally, I think we need to calibrate away from that disempowered concept of hope and recalibrate toward love. If we could collectively reconnect with our reverent love for the incomprehensibly beautiful miracle of our world, all kinds of change could happen fast — and just in the nick of time.

Chris Jordan's film Midway: Message from the Gyre is scheduled to premiere in late 2013. View the trailer.

The Center for Ecoliteracy supports and advances education for sustainable living. You can follow its work at www.twitter.com/ecoliteracy

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On Jul 31, 2013 John Howel Roberts wrote:

there are so many things making changes that the human race are not aware of.

On Jul 29, 2013 PJW wrote:

The opposite of hope is faith. When you have faith that what you are thinking will work out okay then what you are thinking becomes what you are doing.

On Aug 2, 2013 AK47 wrote:

What an amazing article. The first time I tried reading it, I just couldnt go through the entire thing. I couldnt face the denial in my own system and the related pain about me causing so much pain to the planet I live on and the creation that lives on it. Running away felt easier :-)

But then something got me back and I read the entire thing and loved it. I also prayed to get an answer for myself about how to deal with my pain and the one word that was given to me was - gratitude.

I think that apart from living in this disconnected way from our world, I have forgotten the wonders of small day to day things that I take for granted. How the food I eat reaches me, how I get to wear the clothes I like, reach work....in our world logic wins over magic. There is no sense of wonder, of joy, of fascination...of magic that happens to bring things together. A new journey seems to have started. Lets see where this goes.

Thank you for this article.

God bless.

Post Your Reply