Othering & Belonging

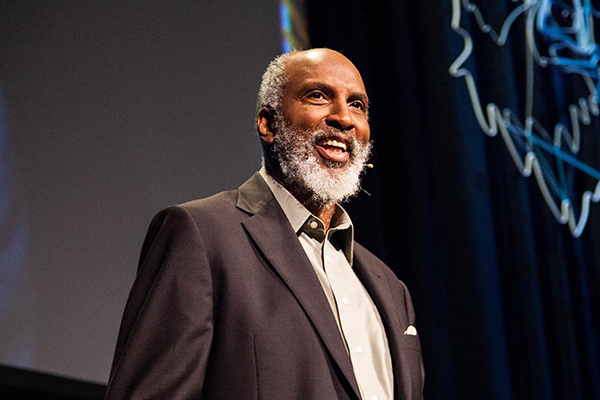

john a. powell is one of the foremost public intellectuals in the areas of civil rights, racism, ethnicity, housing and poverty. Despite a distinguished career, powell spells his name in lowercase on the simple and humble idea that we are part of the universe, not over it. He has introduced into the public lexicon the concepts of “othering and belonging.” For powell, "othering" hurts not only people of color, but whites, women, animals and the planet itself, because certain people are not seen in their full humanity. Belonging is much more profound than access; “it’s about co-creating the thing you are joining” rather than having to conform to rules already set. Born in Detroit the fourth son of a minister and sharecroppers, powell has focused his life’s work on how a belonging paradigm can reshape our world for the better.

john a. powell is one of the foremost public intellectuals in the areas of civil rights, racism, ethnicity, housing and poverty. Despite a distinguished career, powell spells his name in lowercase on the simple and humble idea that we are part of the universe, not over it. He has introduced into the public lexicon the concepts of “othering and belonging.” For powell, "othering" hurts not only people of color, but whites, women, animals and the planet itself, because certain people are not seen in their full humanity. Belonging is much more profound than access; “it’s about co-creating the thing you are joining” rather than having to conform to rules already set. Born in Detroit the fourth son of a minister and sharecroppers, powell has focused his life’s work on how a belonging paradigm can reshape our world for the better.

What follows is the edited transcript of an Awakin Calls interview with powell. You can listen to the call in its entirety here.

Preeta Bansal: Let’s start with your vision of race in this country. From the lens of some, there's been a grand story of halting but real racial progress -- from ending slavery, to eliminating legal segregation, to seeking integration, to working towards tolerance and diversity, and maybe inclusion and equity. From your perspective, what are the realities or limits of our current narrative?

john powell: If we go back to the founding years of the slave trade in the New World, 400 years ago, we see that race as we know it today, didn’t exist at that time. The slave trade created a modern concept of race. The concept of white as a race didn't evolve until almost the end of the 17th century, 66 years after the slave trade started.

Whiteness, blackness, or whatever, was not just given. It was created by the elites for a certain purpose. There was a big rebellion that involved both African workers, former African workers, enslaved people, and British English indentured servants. They weren't "black" and "white" at the time; they were English and African. They came together demanding better conditions. They also demanded access to Native American land. They were relatively successful for a while, and the elite were terrified. They decided to create a wedge between the African and English workers.

They started creating different conditions and a different narrative. They eventually created the Slave Patrol, which was by some accounts the first draft in the world. They drafted Englishmen and their slave counterparts. The new colonies also created laws forbidding marriage between blacks and whites.

“White” was the middle stratum. The elites, who created this stratum did not consider themselves to be white. The role of this middle stratum was allegiance to the elites and dominance over blacks. And variations of that have continued to this day.

When you strip people of their humanity, when you deny people their full participation, when you refuse to see the divine in people--that is called othering. Race is a very powerful way to “other” in the United States. But there are other forms of othering as well. Around the world, we "other" people because of religion, language, immigration status, sexual orientation…We are very creative in finding ways to say that someone's not part of the "WE".

Preeta: How did Native Americans fit into this picture?

john: The interactions with Native Americans happened before the interactions with African people in the United States, but also in Mexico and Latin America. First, they tried to enslave Native Americans. It didn't work for a couple of reasons. One was disease. Europeans introduced germs that indigenous people did not have the resistance to fight. When they try to enslave them, Native Americans didn’t have the physiological makeup to be effectively enslaved. They were on their own land and could escape. To some extent, the Europeans left the Native Americans, except for taking their land and later committing genocide. The initial crops were cotton and Caribbean sugar. The Europeans needed workers who could stand heat and disease. Unfortunately for Africans, they could withstand both.

Preeta: How did this process of "othering" and the creation of race harm the middle layer of “whites?”

john: Economists such as Alberto Alesina and Edward Glaeser show that the economic health in the United States for middle stratum white people is actually lower than their European counterparts. Just think about something like healthcare. We're one of the few "advanced industrial countries" that doesn't have health care.

Another graphic example is Truman. When he was president, he proposed Universal Health Care. The bill almost passed, then someone asked a question: Truman had integrated the troops. "If we have Universal Health Care will the federal government require that the health care facilities be integrated?" Truman said yes, and the people of the United States said, “We don't want it. We’d rather go without health care than to share contact on equal footing with blacks.” This vitriolic position was hardest in the South. Ironically, even today, often the white people who are opposed to the Affordable Care Act are the people who need it the most.

Preeta: I'm struck as you're speaking: even naming the issue has a certain language of othering. We have to use the language of whites, blacks, all of this. What's the role of naming?

john: Some people have argued that since race is socially constructed, shouldn’t we just drop it? But this misses the implications of “socially constructed.” Race is not individually constructed, it’s socially constructed. If we really want to change racism, we have to change the conditions that support it.

For example: The United States is very segregated, not just in terms of schools, but in terms of neighborhoods, where people worship, and how people work. We’ve had laws for many years saying that blacks could not have a job where they managed whites. So first you create the category; then you create the conditions to hold the category in place. We're constantly finding new ways to re-inscribe categories, but we’re also finding new ways to challenge them. Naming can entrench the problem, but it also can disrupt the problem. But a) we won't disrupt the problem just by naming it, and b) we won't keep the problem in place just by naming it. We have to look at our practices, laws, policies, norms, and institutions, our structures themselves, to reflect the kind of aspirations that as a society we want to have.

Preeta: As a nation, what does healing look like to you, and how do we get there?

john: We recognize that we need to heal; but it's not just personal. It's the healing of the country from a deep state of morose. There are more guns than people here. Part of the argument in favor of the second amendment was concern about racism, slavery, and slave revolts. Anxieties and fears are already cooked into the second amendment. Even though we are not worried about a slave revolt now, this is part of our national DNA. We are anxious, scared people. Many try and fix fear by getting a gun.

In the United States, we have to confront the hard edge of the racial hierarchy and the racial disease. It's not just with Black people, or Latinos, or Native people, or Asian people. Oftentimes when you have studies you look at the people who are victimized by these conditions and think about “how do we fix them?” There is stuff that needs to be done. But the heart of racism in the United States is the concept of whiteness and white supremacy. The United States, to this day, has never apologized for slavery. And by some accounts, slavery in the United States didn't really end until 1945. We as a country are still struggling with (1) just even recognizing our past and (2) saying it was wrong. If we can't recognize, if we can't acknowledge our history, our past that's reflected in our present, then we can't heal.

Preeta: Tell us more about what it will take to heal.

john: We have many stories. We're still writing our story. We can write a story where we all belong. Sometimes, people say, "We have to create a space where we are interconnected." I say, "actually we don't; we have to create an awareness." The interconnection is already there. We are interconnected with each other and the Earth. We're from the Earth. We are part of the Earth. We just fail to recognize that. I talk about four splits that are part of the United States and maybe Europe. The splits arose out of that period of racism, colonialism, imperialism, and exploitation. There is a split from nature; a split from the Divine; a split from the Earth; and a split from each other. The final split is the separation between mind and body. Each separation is a wound. Each needs to be addressed and healed.

I'm not big on making people feel guilty or ashamed. We've all done things that we wish we hadn't done. But we are not defined in our personal or collective life by a single act. None of us are a hundred percent bad and none of us are a hundred percent good. We're growing. That's part of the life process. But we can only grow if we recognize the need to grow.

Preeta: I want to move to your personal story. You've talked about the need to shift to a place where we can grow into our true power. You grew up in Detroit, in the 40’s as a sharecropper’s son. There must have been disempowering social structures at that time. How did grow into your power?

john: We have to be careful how we use the word power, right? There's power over and there's power with. I think part of the fear and anxiety that a lot of right-wing people feel now is the sense of loss of power and dominance. This fear is tied to an ontological death.

We love parks and we're afraid of the forest. We have many children's stories about people going into the dark forest and then meeting a wolf or whatever. What those allegories say, is that we like parks because we plan, control, and dominate them. The forest is more organic. It's not under our control and that's scary. We have to shift from power over the park to power with the forest. We recognize we're in relationship. In that sense, power, solidarity and love are not in opposition.

I think for me, the way I got there (and I'm still getting there), is from my family. I reject the story of family from the south, poor sharecroppers, my father dropping out of school in the third grade to work full time when his mother died. My father is legally blind. There were times when we didn't have enough food and times when we were cold. It sounds like a powerful story of lack, if not victimhood.

From that, you would think my father would be physically and emotionally scarred and angry. But if you met him, you would say -- the story doesn’t match the man. My father is one of the happiest, most contented, most loving people on the planet. When you talk to him, he will tell you how blessed he is. And he's getting ready to celebrate his 99th birthday. He is a beacon of love surrounded by love.

In my own life, there was a period when I was consumed by anger, consumed by the scourges of discrimination and racism. But I didn't stay there. I was able to reclaim the foundation that was part of my family. Even today, my family is amazing...

Preeta: You talk about a period where you were consumed with anger, as I imagine a lot of people in similar circumstances would be. What allowed you to move into that place of love? And relatedly, as you talked about your father, there are certain people that are just able to radiate love in the face of unfairness. Gandhi, Mandela, and your father were such people. How does that happen?

john: I don't think we really know. I mean, I have practices. But we have to be a bit careful and humble. It's not to say we shouldn't do the work we need to do. We should have some agency in our lives; but it would be a mistake to think that agency is complete. We're part of something that's so much bigger than us. I went through a period, maybe 20 years, where I really struggled. But I was also given some incredible gifts: being graced by my family and being graced in life. I can't take full credit for it. I do have a contemplative practice that I've done since the 1960's. I try to, as often as I can. I commune with nature. I care about people. I feel that I'm pretty even-keeled.

Years ago, I started meditating. Eventually. I ended up going to India and sitting with Goenka, a Buddhist meditation teacher. I had a profound experience with him. We used to get up 4:00 am and start meditating. Our last meal was at 11:00 am. Each person got one chapati. Goenka is a big man and I had pent-up anger in me. It was like “There's no way he could be eating one chapati a day. I bet you he's sneaking in the kitchen at night having a full meal!” My mind went crazy.

I sat with him and he said, "So how's your meditation going?" and I said to myself, “I'm not opening up to this guy. He's a charlatan.” I said "fine." And he says "well, if I've done anything intentionally or unintentionally to harm you, I ask you for your forgiveness." And I just started crying. When I went back and start sitting after that, I had this experience -- it's hard to explain -- but it's almost like it was a visual experience of anger, frustration, and tightness. I watched it change. I never had the same relationship with anger after that.

Preeta: Coming back a little bit to the first part of our conversation, I know you were careful to say, "It's not just inner work.” What do you see as the role of inner work in bringing about the kind of social transformation we seek, versus work at the policy, structural level within the existing paradigm?

john: You may have heard me cite a jazz cornet player named Don Cherry. In one of his songs, he says, "the inside is not, and the outside is too." It's like a Zen koan, right? I think our duality between inside and outside is false. I helped start this group called Perception Institute. They work with neuroscientists and neuropsychologists on the workings of the mind. Other groups of researchers and academics look at structures and culture. There's sometimes a tension between those two groups. I think that tension is false. If you understand the unconscious and the conscious, they're in constant communication with structures and culture. They're constantly communicating, interacting, shaping, and co-creating each other.

My practice is about a world where we're both inside and outside. We are called upon to bridge, to bring these two things together. You bridge partially through engaging in empathetic and compassionate stories, and through practice, and listening. You engage in each other's suffering. Eventually you reveal that the internal and the external are not two different things.

Preeta: Let’s go back to the ideology of whiteness versus white people. Can you tell us about how we can bridge and show compassion for this middle stratum, composed of socially constructed white people? How can we help them heal, and how can that bridging be done, so they can see their suffering and feel compassion for their own suffering?

john: I think that's really important. We work with the Greater Good Science Center. The great teacher and connector in many ways is suffering; and not simply blaming our suffering on someone else. Other people may participate in creating suffering, but we are taught that life involves many types of suffering. People want to be recognized and not being recognized is suffering.

There's this Zulu word, which is Sawubona, which means "I see you" or "we see you." It's also interpreted as "the Divine in me sees the Divine in you," and as a corollary phrase, which says "I am because you are." Part of our work is to open that space and to be willing to listen.

Nelson Mandela was a consummate master bridger. The children in South Africa did not want to be forced to learn Afrikaander, the language of the oppressor. Nelson Mandela was on Robbens Island and asked his jailers to teach him Afrikaander. When he got out of prison, he met with the head of the South African Army. This general believed in racial hierarchy. He also believed that whites should win the war and that blacks couldn't be trusted -- they were not fully human. Nelson Mandela invited him to his home and served him tea. When they started negotiating, the negotiations were in Afrikaander. Mandela offered a bridge and the general agreed to a ceasefire. Later the general spoke at a eulogy for Nelson Mandela in Mandela's language of Xhosa.

When I once talked to Pastor McBride about bridging, he said "So are you saying I have to bridge with the devil?" I said, "don't start there; start with short bridges, which might be family members, which might be people who you know but don't quite agree with; after you wake up that capacity in yourself, you can start building longer bridges."

I think there are a lot of white people who are hurting and trying to figure out something different. We do this together, not just with white people, but with gay people, straight people, Native people -- we listen to each others’ stories; we build a bigger story and a bigger "we." We don’t insist that our story is the only one that really counts. All stories are heartfelt.

I've done this with white people -- I was asked to talk to some conservative whites in, I think it was rural Alabama, about the Affordable Care Act. A couple hundred people came out. They were not happy to be there. I was questioning why I was there. I said, "Let's not talk about the Affordable Care Act, let's talk about your own lives…how many of you have lost insurance because you lost your job? Please stand up. How many of you have children at home who the insurance company refused to insure because they had a pre-existing condition? Please stand up. How many of you have had the doctor prescribe something that you needed to live, and the insurance company said no, it was too expensive or the wrong drug? Please stand up.” I asked a couple more questions -- and by now everybody is standing up -- and then I said, "so how does this feel?" Then I said, "that's what the Affordable Care Act is trying to solve."

Everybody was engaged. I was no longer a black professor from outside of the area. I was someone witnessing and validating their suffering. Then I pivoted and started talking about blacks and Latinos. I didn't lose one person; but I didn’t start by talking about blacks and Latinos; I didn’t talk about white supremacy or white privilege. I didn't try to shame them or blame them. I acknowledged their own pain. I started by seeing them. Once they were seen, they were willing to see others. We heal as we cultivate the willingness to see people and, if we can, to love people, not because of what they're doing but because of what they've been through. We're all connected.

Syndicated from Awakin Calls. This transcript was edited by Bonnie Rose. Bonnie Rose is the Senior Minister at the The Ventura Center for Spiritual Living. Their mission is “be love, share love, serve love.” Bonnie also encourages greater love in the world through her blog, www.dailybeloved.org.

On Aug 1, 2020 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Powerful, thank you, Indeed once we listen to each other's stories we are or can be changed and can build bridges between more easily. With you: "I think there are a lot of white people who are hurting and trying to figure out something different. We do this together, not just with white people, but with gay people, straight people, Native people -- we listen to each others’ stories; we build a bigger story and a bigger "we." We don’t insist that our story is the only one that really counts. All stories are heartfelt."

Post Your Reply