5 Ways to Build Solidarity Across Our Differences

The victory of Brexit in the UK has provoked a confrontational atmosphere, characterised by some as a growing gulf between left-leaning pro-Europe liberals and groups of poor and disenfranchised people voting against the ‘establishment.’ The former accuse the latter of prejudice and/or ignorance. The latter see the former as elites who don’t understand their situation and are reluctant to oppose the status quo. Prejudice and self-interest are likely part of the picture on both sides.

The victory of Brexit in the UK has provoked a confrontational atmosphere, characterised by some as a growing gulf between left-leaning pro-Europe liberals and groups of poor and disenfranchised people voting against the ‘establishment.’ The former accuse the latter of prejudice and/or ignorance. The latter see the former as elites who don’t understand their situation and are reluctant to oppose the status quo. Prejudice and self-interest are likely part of the picture on both sides.

But binary decision-making processes like referendums reflect positions on one issue at one point in time, not whole people with complex lives. Simplistic versions of events can become entrenched, leaving us stuck in different silos. How can we become unstuck? How do we foster solidarity between people who could be allies for radical change but who view each other with suspicion and anger?

These are questions that concern us at Skills Network, a women’s cooperative in Lambeth, south London. The two of us founded the organisation in 2011 as a space for women from diverse backgrounds to share concerns, receive training on supporting children’s education, and undertake research on issues affecting local families. We wanted to dispense with top-down approaches and work as equals, hoping that radical ways of tackling problems would emerge over time. Our group includes ‘leave’ and ‘remain’ voters, professional women, women who have never been to school or who left early, lifelong Londoners, recent immigrants, women on benefits, women in low-paid work, ex-prisoners and victims of domestic abuse.

Our values and positions sometimes clash. There has been profound disagreement and suspicion. Cliques have formed and arguments have brewed. Nonetheless, we have found ways to understand each-other, to feel the interconnectedness of our struggles and move forward together.

Clearly, local experience can’t simply be scaled up to the level of whole societies, but after the EU referendum there was no ‘growing gulf’ between ‘leave’ and ‘remain’ voters in our network. So we think our experience may resonate with people who want to come together with others who might disagree with them on divisive issues. What have we learned?

What undermines solidarity? Three lessons.

1. Don’t assume you know where people are coming from—or that it’s your role to ‘educate’ them.

K: It’s not okay to say you don’t feel comfortable among Muslim members and that it is ‘wrong’ that women wear hijab. It feels like out and out prejudice…

H: You know me, I don’t dislike anyone. But we’ve fought hard for black women’s rights since the 1970s. And when women put themselves under that headscarf it feels like they’re betraying what we fought for.

These quotes paraphrase a two-hour conversation between Kiran and another core member of the network who we’ll call ‘H.’ H had made what we as co-founders heard as Islamophobic comments. We were outraged: H was someone we liked and respected. She was also a single, disabled mother who had spent time in prison. She’d experienced discrimination herself. How could she do it to others?

After some hesitation, predicting an uncomfortable conversation about immigration, K challenged H, feeling that she had to ‘educate’ H on how she was wrong, or misled. But it was K who needed to learn about H’s experience of social struggle and how this affected her position. H went on to have considered debates with Muslim members of the network about why they wore the headscarf. We have never reached consensus on this issue, but we’ve reached a place where no one feels silenced or undermined.

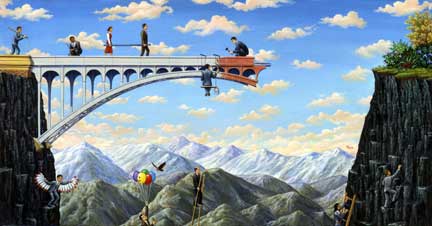

Listening well, staying curious and open to challenge when you feel uncomfortable or morally ‘right’ is like walking a tightrope. It’s easy to become over-focused on how to ‘convince’ the other person and hear only what you expect to hear.

To disrupt this habitual thinking, K and H used an approach we had practised called ‘listening from a position of not knowing.’ They allowed each other to speak without interruption for two minutes and used ‘curious’ questions to open up the other’s story. K thought by ‘wrong’ H meant ‘bad,’ but on probing learned that she actually meant ‘unjust.’ This transformed the discussion. They also used a ‘perspective board’ to externalise their disagreement, a technique that “shifted our usual logic” as H put it.

Sometimes, though, we slip from the tightrope. When members raise concerns that trigger our ‘liberal values’ sensors as founders we react in ways that shame, patronise or stifle them. Later on we might realise that our assumptions were wrong. But by then the bonds between us are weakened.

2. Power differentials distort conversations.

“I’m in ‘the system.’ I need to watch what I say. You don’t know what can get you in trouble."

Our professional backgrounds, manner and class meant other Skills Network members were initially worried that we would have official power over them. They were subtly guarded in what they shared with us and how much they spoke out—so subtly that we didn’t realise for some time what was happening. But as we developed formal, non-hierarchical structures that put everyone on an equal level, people felt safer to challenge us. As M, another member put it:

“the majority of people coming through our doors believed they were at the bottom of the hierarchy ...when we’ve kicked off the hierarchical structure, for the first time in ages for some of them in a public space, they are as important as everyone else in the room.”

Nevertheless, informal power hierarchies distort interactions. We as founders unconsciously manoeuvre discussions, using our university education to out-argue doubters. Often we think that we’ve persuaded people only to discover later that they have ‘managed’ us; smiling and playing a learned subservient role. Other unacknowledged hierarchies emerged as we expanded: between older members and new joiners; or those who spoke good English and new learners; or those who were managing financially and those who weren’t.

We examine these hierarchies using an interactive ‘power ladder’ and role-play. We try to prioritise the least-heard voices in meetings, use non-verbal discussion methods, and are vigilant about sharing information fully and accessibly. This helps, but constant awareness and reflection is crucial. Underestimating how much power hierarchies distort conversations can kill any chance of real solidarity emerging.

3. Value the analytic understanding of people at the sharp end of power

"I’m a poor black woman so everyone wants my ‘gritty story,’ how nasty my life is. I do have a brain. I notice and think and have ideas. How about asking me for those?"

This rebuke from R came two years into our work. She was right. We thought our role was to elicit people’s ‘stories’ and then do the ‘intellectual’ work of analysis ourselves—keeping people in the role of ‘the researched,’ undermining their status and squandering the chance to develop shared visions. Different members of the group have managed life with abusive partners, navigated social service systems, and even witnessed the complete breakdown of social relations in Mogadishu, Somalia. These experiences have rendered them adept at unpicking and critiquing systems and policies.

When this realisation hit us, we designed sessions to undertake research analysis and organisational strategizing together. This collective inquiry, which places all our knowledges on an equal level, has transformed our sense of mutual respect and shared purpose.

What strengthens solidarity? Two more lessons.

1. Creating a bigger us.

Focusing on a personalised enemy like Jobcentre advisors, bailiffs or teachers, or on an opposing group like ‘Remainers’ vs ‘Brexiteers,’ is an easy way to create a temporary feeling of solidarity. But as M commented after an antagonistic discussion about Jobcentre workers:

“Though it was a relief for a while to get it all out … we all left feeling dejected. It’s horrible and oppressive thinking that people are bad. It makes everything feel hopeless.”

So we invited Jobcentre staff in for a ‘citizens’ jury session’ to exchange ideas as equals. The session revealed common goals and frustrations. Everyone felt constrained by the current punitive set-up which, as one member said, “works for nobody, we need to come together to challenge the ideas that divide our humanity.”

Together we have built a more expansive solidarity which bonds us against the system as the oppressor. We’ve also explored alternative models like the ‘Core Economy’ which places unpaid care and relationship-building at the centre of the economic system. These give us something to hope for and work towards, rather than just oppose, staving off exhaustion and fatalism.

2. Rethinking accepted ideas and frameworks together.

We started off assuming that being ‘self-reliant’ was a desirable goal, but came to understand that continuous pressure to achieve this from the welfare system was oppressive, and often unachievable for women with young dependents and multiple barriers to financial security. It was also an illusion, since every one of us relies on networks and connections.

So we started exploring ‘interdependence’ as an alternative frame, developing new ways to strengthen our reliance on each other and increase our collective power. We also discussed ‘weaknesses’ as having a value of their own—as cracks through which we could let others in and where bonds could be strengthened. Creating and trying to enact these frameworks together has created a profound and robust affinity between us: one stronger than many of us have with our socio-economic peers.

In this post-Brexit era, seeking to convince ‘ignorant’ leave voters they are wrong, or superficial attempts to listen to their ‘stories,’ won’t help us become unstuck. We need to start engaging as equals, however uncomfortable and messy this might be. Since founding Skills Network we have learned that we don’t have all the answers, and that we can be just as misled and prejudiced as anyone else. But standing shoulder to shoulder with people across our differences and creating new understandings and visions together is where the real transformative potential lies.

***

For more inspiration, join this week's Awakin Call with Yoav Peck, co-director of the Sulha Peace Project, that brings together Israelis and Palestinians who meet regularly to "encounter the other in our full humanity". More details and RSVP info here.

This article originally appeared in the Transformation section of OpenDemocracy. Kiran Nihalani and Peroline Ainsworth co-founded Skills Network in 2011. Prior to this, Kiran worked in the third sector in frontline and campaigning roles. She is currently undertaking PhD research about small-scale, non-hierarchical models of creating welfare. Peroline is a special educational needs teacher and social researcher. Previously she worked in development in Africa and the Middle East.

On Feb 17, 2017 Sidonie Foadey wrote:

What an authentic and a vulnerable approach this is! Quite original too, it feels like true solidarity to me. It's remarkably brave, inspiring and thought-provoking! Thanks for sharing.

Post Your Reply