The Value of Not Understanding Everything: Grace Paley's Advice to Aspiring Writers

"Luckily for art, life is difficult, hard to understand, useless, and mysterious."

“As a person she is tolerant and easygoing, as a user of words, merciless,” the editors of The Paris Review wrote in the introduction to their 1992 interview with poet, short story writer, educator, and activist Grace Paley (December 11, 1922–August 22, 2007). Although Paley herself never graduated from college, she went on to become one of the most beloved and influential teachers of writing — both formally, through her professorships at Sarah Lawrence, Columbia, Syracuse University, and City College of New York, and informally, through her insightful lectures, interviews, essays, and reviews. The best of those are collected in Just As I Thought (public library) - a magnificent anthology of Paley’s nonfiction, which cumulatively presents a sort of oblique autobiography of the celebrated writer.

Grace Paley by Diana Davies

In one of the most stimulating pieces in the volume - a lecture from the mid-1960s titled “The Value of Not Understanding Everything,” which does for writing what Thoreau did for the spirit in his beautiful meditation on the value of “useful ignorance” - Paley examines the single most fruitful disposition for great writing:

The difference between writers and critics is that in order to function in their trade, writers must live in the world, and critics, to survive in the world, must live in literature. That’s why writers in their own work need have nothing to do with criticism, no matter on what level.

[…]

What the writer is interested in is life, life as he is nearly living it… Some people have to live first and write later, like Proust. More writers are like Yeats, who was always being tempted from his craft of verse, but not seriously enough to cut down on production.

Therein, she argues, lies the key to why writers write. Echoing Joan Didion - “Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write,” she wryly observed in the classic Why I Write - Paley reflects:

One of the reasons writers are so much more interested in life than others who just go on living all the time is that what the writer doesn’t understand the first thing about is just what he acts like such a specialist about — and that is life. And the reason he writes is to explain it all to himself, and the less he understands to begin with, the more he probably writes. And he takes his ununderstanding, whatever it is — the face of wealth, the collapse of his father’s pride, the misuses of love, hopeless poverty — he simply never gets over it. He’s like an idealist who marries nearly the same woman over and over. He tries to write with different names and faces, using different professions and labors, other forms to travel the shortest distance to the way things really are.

In other words, the poor writer — presumably in an intellectual profession — really oughtn’t to know what he’s talking about.

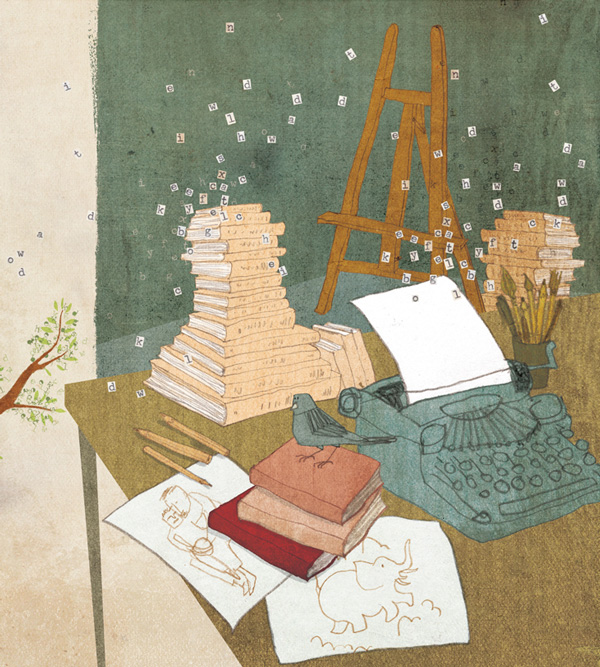

Illustration by Kris Di Giacomo from 'Enormous Smallness' by Mathhew Burgess, a picture-book biography of E.E. Cummings.

With a skeptical eye to the familiar “write what you know” dictum of creative writing classes, Paley makes a case for the opposite approach in extracting the juiciest raw material for great writing:

I would suggest something different… what are some of the things you don’t understand at all?

[…]

You might try your father and mother for a starter. You’ve seen them so closely that they ought to be absolutely mysterious. What’s kept them together these thirty years? Or why is your father’s second wife no better than his first? If, before you sit down with paper and pencil to deal with them, it all comes suddenly clear and you find yourself mumbling, Of course, he’s a sadist and she’s a masochist, and you think you have the answer — drop the subject.

In classic Paley style, where what appears to be subtle sarcasm turns out to be a vehicle for great sagacity, she adds:

If, in casting about for suitable areas of ignorance, you fail because you understand yourself (and too well), your school friends, as well as the global balance of terror, and you can also see your last Saturday-night date blistery in the hot light of truth — but you still love books and the idea of writing — you might make a first-class critic… In areas in which you are very smart you might try writing history or criticism, and then you can know and tell how all the mystery of America flows out from under Huck Finn’s raft; where you are kind of dumb, write a story or a novel, depending on the depth and breadth of your dumbness…

When you have invented all the facts to make a story and get somehow to the truth of the mystery and you can’t dig up another question - change the subject.

Cautioning that writing fails when “the tension and the mystery and the question are gone,” she concludes:

The writer is not some kind of phony historian who runs around answering everyone’s questions with made-up characters tying up loose ends. She is nothing but a questioner.

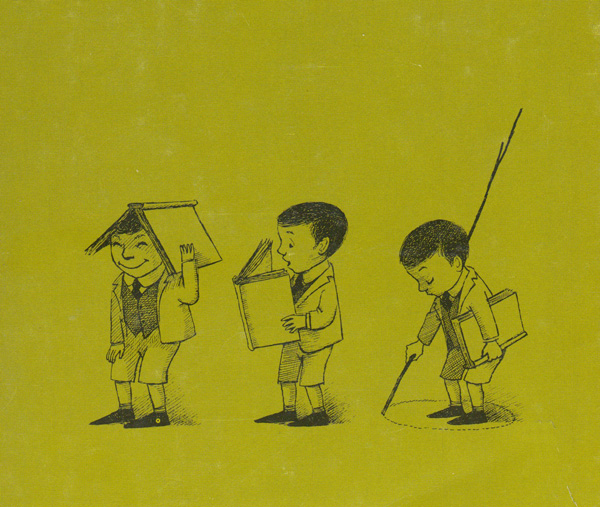

Illustration by Maurice Sendak from 'The Big Green Book' by Robert Graves.

A few years later, Paley revisits the subject in a 1970 piece from the same volume titled “Some Notes on Teaching,” in which she offers fifteen insights as useful to aspiring writers as they are to professional writers like herself “who must begin again and again in order to get anywhere at all.” Noting that she aims to “stay as ignorant in the art of teaching” as she wants her students to be in the art of writing, she observes that the assignments she gives are usually questions which have stumped her, ones which she herself is still pursuing.

She first turns to the integrity of language, so often squeezed out of writers by their education:

Literature has something to do with language. There’s probably a natural grammar at the tip of your tongue… If you say what’s on your mind in the language that comes to you from your parents and your street and friends, you’ll probably say something beautiful. Still, if you weren’t a tough, recalcitrant kid, that language may have been destroyed by the tongues of schoolteachers who were ashamed of interesting homes, inflection, and language and left them all for correct usage.

She then offers an assignment that puts into practice this essential art of “ununderstanding,” with the instruction of being repeated whenever necessary:

Write a story, a first-person narrative in the voice of someone with whom you’re in conflict. Someone who disturbs you, worries you, someone you don’t understand. Use a situation you don’t understand.

Paley raises a dissenting voice in literary history’s many-bodied chorus of celebrated writers who extol the creative benefits of keeping a diary:

No personal journals, please, for about a year… When you find only yourself interesting, you’re boring. When I find only myself interesting, I’m a conceited bore. When I’m interested in you, I’m interesting.

(It is worth offering a counterpoint here, by way of Vivian Gornick’s excellent advice on how to write personal narrative of universal interest and Cheryl Strayed’s observation that “when you’re speaking in the truest, most intimate voice about your life, you are speaking with the universal voice.”)

Ignoring John Steinbeck’s admonition — “If there is a magic in story writing, and I am convinced there is,” he asserted in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “no one has ever been able to reduce it to a recipe that can be passed from one person to another.” - Paley offers if not a recipe then a pantry inventory of the two key ingredients necessary for great storytelling:

It's possible to write about anything in the world, but the slightest story ought to contain the facts of money and blood in order to be interesting to adults. That is, everybody continues on this earth by courtesy of certain economic arrangements; people are rich or poor, make a living or don’t have to, are useful to systems or superfluous. And blood — the way people live as families or outside families or in the creation of family, sisters, sons, fathers, the bloody ties. Trivial work ignores these two facts.

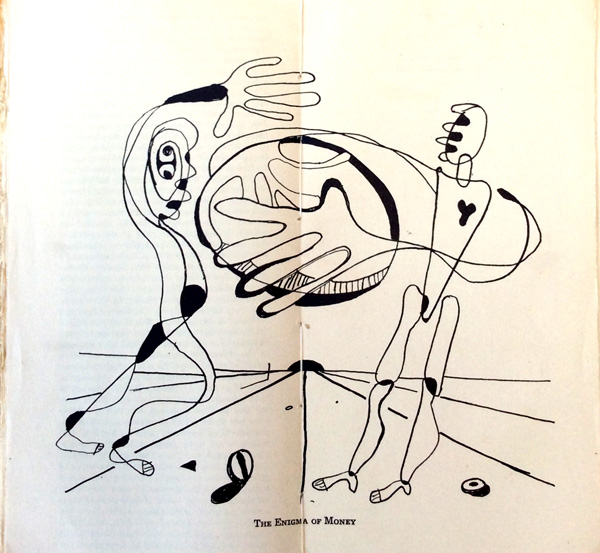

Art from the original edition of Henry Miller's 'Money and How It Gets That Way.'

She returns to the essential fork in the vocational road that separates writers from critics:

Luckily for art, life is difficult, hard to understand, useless, and mysterious. Luckily for artists, they don’t require art to do a good day’s work. But critics and teachers do. A book, a story, should be smarter than its author. It is the critic or the teacher in you or me who cleverly outwits the characters with the power of prior knowledge of meetings and ends.

Stay open and ignorant.

Echoing Nadine Gordimer’s enduring wisdom on the writer’s task “to go on writing the truth as he sees it,” Paley adds:

A student says, Why do you keep saying a work of art? You’re right. It’s a bad habit. I mean to say a work of truth.

What does it mean To Tell the Truth?

It means — for me — to remove all lies… I am, like most of you, a middle-class person of articulate origins. Like you I was considered verbal and talented, and then improved upon by interested persons. These are some of the lies that have to be removed:

a. The lie of injustice to characters.

b. The lie of writing to an editor’s taste, or a teacher’s.

c. The lie of writing to your best friend’s taste.

d. The lie of the approximate word.

e. The lie of unnecessary adjectives.

f. The lie of the brilliant sentence you love the most.

She ends by urging aspiring writers to learn from the masters of this art of truth-telling:

Don’t go through life without reading the autobiographies of

To that, I would heartily add the autobiography of Oliver Sacks - had she lived to read it, Paley may well have concurred.

This article originally appeared in Brain Pickings and is republished with permission. The author, Maria Popova, is a cultural curator and curious mind at large, who also writes for Wired UK, The Atlantic and Design Observer, and is the founder and editor in chief of Brain Pickings.

On Jul 31, 2015 infishhelp wrote:

Such an optimist. I've know artists and I seemed to draw truth out of them because I asked honest questions about their art. Art is a very unconscious activity that gets ideas out into the conscious for expression. The truth was not in their art. The art was a work of lie to disguise the truth hidden from their very self with such absurdity that even a fool like myself could see through it. Artists are brilliant and often painfully self-conscious. They desperately want the True Light, and must be willing to look away from their own brilliance... to have peace that passes all understanding.

Post Your Reply