"I Wish My Teacher Had Known..." - Adults on How Teacher Empathy Could Have Changed Their Lives

Photo by U.S. Department of Education

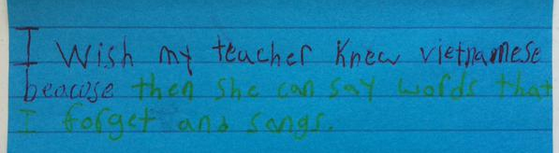

Kyle Schwartz, an elementary school teacher in Denver, recently came up with an activity for her third-grade class that went viral. Employed at a school where 92 percent of kids qualify for free or reduced lunch , Schwartz was looking for a way to better understand her students. She handed out notecards and asked them to finish this sentence: “I wish my teacher knew…”

The results were heart-wrenching:

Although it’s a minor problem in comparison to what some of Schwartz’s students are going through, to this day I still wish my teachers had known how hard it was for me to give presentations. Forcing me into public speaking did nothing to alleviate my fear of it.

The terror. The sweating. The sleep deprivation. The dread that swept over my body like the specter of death the moment my name was called. I had anxiety over public speaking so bad, I would be stressed out from the day the project was announced. I’d be so nervous the night before that I would be utterly unable to sleep and so, on top of being terrified, I had to present in a groggy, sleep-deprived, there-isn’t-enough-coffee-in-the-universe fog. These projects made me miserable.

Watching Schwartz’s story take off on the Internet got me thinking about how much we are affected by experiences in school beyond our classes, extracurricular activities, and cafeteria gossip. Most kids deal with issues at home, illnesses, or disabilities that are invisible to others. These challenges affect every part of the learning process—including attention span, classroom behavior, and interaction with other kids. Every child has different needs, but the inflexibility of the education system in the United States often leaves behind those who don’t fit in. If you can’t learn to read the way reading is taught, you’re out of luck. Roadblocks like this hurt grades, lower confidence, and often haunt us into adulthood.

Why does school have to be something kids “survive”?

My teachers did nothing to address my phobia of public speaking, and I never learned how to give a presentation without being stricken with terror. Today, that fear limits my career possibilities. I could seek help for it on my own now, but it would have been so much easier (and cheaper) if someone had understood and intervened when I was young.

In order to explore this issue further, I embarked on a project of my own and asked some of my friends to finish this sentence: “I wish my teacher had known…”

Here are some of their responses, which have been lightly edited:

“I wish my teacher had known how much it hurt me emotionally and intellectually when they would teach other subjects and work on projects, which I missed while I was in my special class for dyslexia.”

Janelle has the common learning disability dyslexia, which affects about10 percent of the human population. Because she didn’t learn to read like most kids, she was removed from classes each day for special instruction with other dyslexic kids. Because of that, she missed out on things that the rest of the student body experienced, like math lessons and arts and crafts projects. The knowledge gaps left Janelle thinking something was wrong with her, a feeling she struggled with through middle and high school.

“I wish my teacher had known that telling kids not to pick on me because I was ‘disabled and sensitive’ was not adequate help and actually counterproductive.”

Addison was born with cerebral palsy, which caused his left arm and leg to be smaller and weaker than his right. It affected his ability to run, play sports, and generally keep up with the other boys. As a result, he was bullied from a young age. Teachers did little to help him, and pointing out his disability only made him a more obvious target.

"I wish my teacher had known that just because I didn't talk didn’t mean I didn’t understand. I wish my teacher had known that when they called my house to complain about my silence, my parents beat me for it.”

Janessa was born with a hearing disorder that left her mostly nonverbal through much of elementary school. Her teachers assumed Janessa’s silence meant she was less intelligent than her peers or that she wasn’t trying hard enough. She remembers how her teachers belittled her, yelled at her, and bullied her in front of her classmates, which in turn increased the bullying she endured from other kids. Unaware of abuse at home, teachers complained about Janessa’s behavior to her parents, which only exacerbated her abusive home life.

In sixth grade, a standardized test revealed she read at a college level. As an adult, Janessa recognizes the potential that had been hiding beneath her quiet surface and feels her teachers could have done more to understand her needs. "An intelligent curiosity dwelled behind my silence," she said. "In not stopping the bullying by my peers, they further enforced my silence."

“I wish they had known in high school that I was having a catatonic panic attack and that's why I was scared to go to school. Or that I took so many bathroom breaks because I had to throw up any amount of food I ate. I wish they knew that we were too poor to buy calculators and flash drives, and that I didn't know how to use PowerPoint because we didn't have that on our computer.”

Poor attendance and frequent bathroom breaks are often assumed to be the result of laziness and disinterest in school. In Damielle’s case, her mental illness made it difficult to go anywhere, let alone spend all day in school. While many teen girls suffer from eating disorders like bulimia, a lot of school administrators remain unaware of the issue and are therefore unsympathetic to kids who ask for frequent bathroom breaks or can’t focus due to lack of nutrition.

We need to change the way we think about education.

As a former classmate of Damielle’s, I remember that PowerPoint presentations were a required aspect of many school projects. Having grown up in a middle-class family, it never occurred to me that some kids’ parents might not be able to afford the program, and that kids like Damielle had to try and complete presentations in the library or at friends’ homes. None of Damielle’s teachers recognized her behavior as a sign of a bigger problem until high school, but by then the years of struggling had left their mark.

All of these people, including myself, survived school and are now functioning adults. The question is, why does school have to be something kids “survive”? It seems deeply unfair that the friends I talked to had so much trouble in school because of differences they couldn’t control.

These stories reinforce my belief that the U.S. school system can and should be so much more than it is now. We need to change the way we think about education. Schools need to be flexible enough to create alternate paths around obstacles like poverty, disability, and illness. Teachers need more resources, more help, and smaller class sizes so they have an easier time getting to know their students.

With CNN and The Today Show reporting on Schwartz’s class project, she has become a leading voice in the national conversation about the importance of teachers building trust with their students. Educators all over the country have been inspired to learn more about their students’ individual needs and personal hurdles by holding their own activities around “I wish my teacher knew.” What started as one small classroom project has sparked a movement to improve the U.S. education system through simple empathy and understanding.

This article is shared here with permission from YES! Magazine, a national, nonprofit media organization that fuses powerful ideas with practical actions. The author, Lindsey Weedston, is a Seattle-based feminist blogger with a creative writing degree that everyone told her would be useless. She spends her time writing about various human rights and social justice issues on her blog Not Sorry Feminism and dabbles in video game reviews and commentary.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

2 Past Reflections

On May 28, 2015 Heather Shinn wrote:

Great information and insights! What are the appropriate solutions to these scenarios? Some seem obvious but others aren't. General ed teachers are not adequately trained during their own schooling HOW to accommodate. They are often perplexed, apprehensive, and anxious about various disabilities and socio-economic situations. It is never enough to point out what a problem is without also offering ways to fix it or accommodate it. I wonder what responses you would get if teachers or parents were asked a similar question? The different perspectives could reveal where change needs to happen.

On Jul 30, 2015 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

insightful. Another great example that everyone has a story and those back stories affect every aspect of our lives. Compassion and empathy are key.

I also agree with Heather about providing potential solutions to each scenerio. I would think that the programs offered surrounding this project do just that, it would have been wonderful to read even one of the solutions in this article.

Post Your Reply