A Seizure of Happiness: Mary Oliver on Finding Magic in Life's Unremarkable Moments

How to revel in the “sudden awareness of the citizenry of all things within one world.”

Nearly a century before modern neuroscience presented the uncomfortable finding that mind-wandering is making us unhappy, Bertrand Russell contemplated the conquest of happiness and pointed to the immense value of “fruitful monotony” — a certain quality of presence with the ordinary rhythms of life. The diaries and letters of humanity’s greatest minds are strewn with such instances of finding happiness in simple everyday moments, but no one captures the humble grace of presence better than Mary Oliver in one particularly bewitching passage from her altogether enchanting Long Life: Essays and Other Writings (public library).

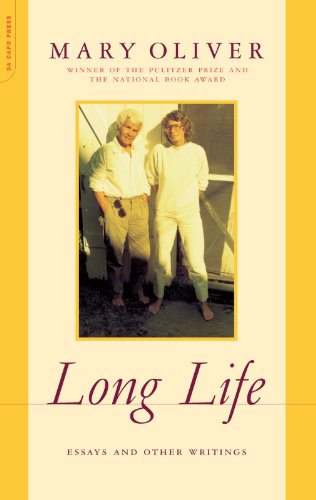

Mary Oliver in 1964. Photograph by Molly Malone Cook from Oliver's 'Our World.' Click image for more.

With Thoreau’s attentiveness to the outer world and Rilke’s attentiveness to the inner, Oliver writes:

On the windless days, when the maples have put forth their deep canopies, and the sky is wearing its new blue immensities, and the wind has dusted itself not an hour ago in some spicy field and hardly touches us as it passes by, what is it we do? We lie down and rest upon the generous earth. Very likely we fall asleep.

[…]

Once, years ago, I emerged from the woods in the early morning at the end of a walk and — it was the most casual of moments — as I stepped from under the trees into the mild, pouring-down sunlight I experienced a sudden impact, a seizure of happiness. It was not the drowning sort of happiness, rather the floating sort. I made no struggle toward it; it was given.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the conditions of this total, effortless surrender to happiness parallel the “flow” state typical of creative work.

Oliver, who has extolled the urgency of belonging to the world as the supreme act of aliveness, writes:

Time seemed to vanish. Urgency vanished. Any important difference between myself and all other things vanished. I knew that I belonged to the world, and felt comfortably my own containment in the totality. I did not feel that I understood any mystery, not at all; rather that I could be happy and feel blessed within the perplexity — the summer morning, its gentleness, the sense of the great work being done though the grass where I stood scarcely trembled. As I say, it was the most casual of moments, not mystical as the word is usually meant, for there was no vision, or anything extraordinary at all, but only a sudden awareness of the citizenry of all things within one world: leaves, dust, thrushes and finches, men and women. And yet it was a moment I have never forgotten, and upon which I have based many decisions in the years since.

Illustration by Sydney Smith from 'Sidewalk Flowers,' a visual ode to living with presence in the modern urban world. Click image for more.

Indeed, this immersive attentiveness to the casual, unremarkable, yet remarkably enlivening moments of life is the raw material of Oliver’s genius, of her singular gift for bridging that vast abyss between the mind and the heart. (“Attention without feeling,” she wrote in her beautiful memoir, “is merely a report.”) She considers how the unremarkable becomes the screen against which the remarkable shines its luminous beam:

My story contains neither a mountain, nor a canyon, nor a blizzard, nor hail, nor spike of wind striking the earth and lifting whatever is in its path. I think the rare and wonderful awareness I felt would not have arrived in any such busy hour. Most stories about weather are swift to describe meeting the face of the storm and the argument of the air, climbing the narrow and icy trail, crossing the half-frozen swamp. I would not make such stories less by obtaining anything special for the other side of the issue. Nor would I suggest that a meeting of individual spirit and universe is impossible within the harrowing blast. Yet I would hazard this guess, that it is more likely to happen to someone attentively entering the quiet moment, when the sun-soaked world is gliding on under the blessings of blue sky, and the wind god is asleep. Then, if ever, we may peek under the veil of all appearances and partialities. We may be touched by the most powerful of suppositions — even to a certainty — as we stand in the rose petals of the sun and hear a murmur from the wind no louder than the sound it makes as it dozes under the bee’s wings. This, too, I suggest, is weather, and worthy of report.

Long Life, which also gave us Oliver on how habit gives shape to our inner lives, is exquisite and enlivening in its entirety. Complement it with Oliver’s gorgeous reading of “Wild Geese,” her moving remembrance of her soul mate, and her playful meditation on the magic of punctuation.

If you haven’t yet devoured Oliver’s wonderfully wide-ranging On Beingconversation with Krista Tippett, give yourself this seizure of happiness:

This article originally appeared on http://www.brainpickings.org and is republished here with permission.

Maria Popova is a cultural curator and curious mind at large, who also writes for Wired UK, The Atlantic and Design Observer, and is the founder and editor in chief of Brain Pickings.