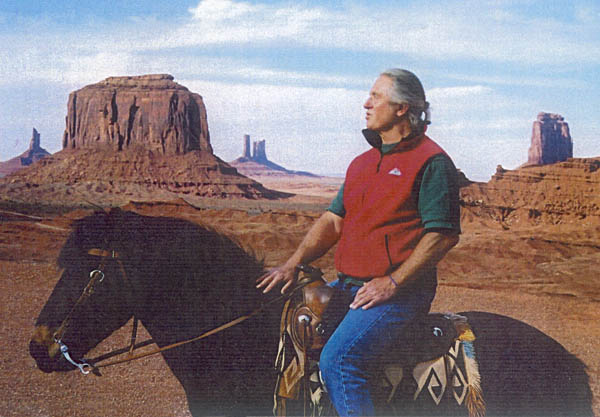

All Life is Sacred: A Conversation with John Malloy

John Malloy’s father was in Army Intelligence and assigned to the U.S. Embassy in Shanghai when Malloy was an infant. When Chiang Kai-shek fled China three years later, in 1949, Malloy’s family was the last one out of Shanghai on a plane. From there they went to the Philippines during the Huk rebellion. And then there was Java and Borneo and jungle living. By the time Malloy was seventeen, he had moved forty-four times. In his young life as a rolling stone, Malloy learned to rely on himself. Whatever allies and friends he might have begun to cultivate in one place were always torn away by his constant displacement. In schools in New York, Washington D.C., San Francisco, and Oakland, as the new kid, he learned to fight. Every day was a trial. While living in San Francisco he ended up in juvenile hall. Later, he did time for assaulting the perpetrators of a rape. Being unprotected from bullies in school wasn’t so different from how it was in jail. The big eat the little. But Malloy was a warrior. It was during his time in jail that something crystallized for him. “I knew that I was going to clean up my mess and spend the rest of my life working in institutions to help take care of the people who no one else was taking care of.”

His resolve led to the creation of a school for young people who had been incarcerated, the Foundry School. Intuitively at first, and later in a more conscious way, he arrived at highly effective ways of helping young people whose lives had spiraled down into violence and crime. Word of Malloy’s integrity, courage, and effectiveness spread. It’s how he began to meet Native Americans who entrusted their at-risk children into his care. For Malloy, it was a pivotal event. In Native American spirituality he found a way of looking at the world that resonated most deeply with his own experience.

By the time I met Malloy his formative years were decades in the past. A profound alliance with Native Americans was well established. He was heading up the Santa Clara Unified School District’s work with problem children while working pro bono with at-risk youth in a number of other ways. Out of his immersion in the shadow worlds of war and incarceration, his power has been shaped into a rare capacity to help young men headed on a path to ruin.

—Richard Whittaker

RICHARD WHITTAKER

I think of you having a very strong Native American presence. What is your Native American connection?

JOHN MALLOY

That’s my religion, for a lot of reasons.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

How did that happen?

JOHN MALLOY

The Native people came to me, because they heard of my good work with children. This was in the ’70s. I was directing and managing The Street Academy.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

What is The Street Academy?

JOHN MALLOY

It was called the Foundry School. Before that I worked for seven years in a high-risk unit for kids who were incarcerated for serious crimes.

Eventually I left my work at juvenile hall to help start The Foundry School with two of my friends. We wanted to turn on the turned-off kids getting out of juvenile hall. The schools didn’t want them. There was no place for them to go. They needed a transition. So we were chosen.

Eighty percent of Native people between eighteen and thirty have been incarcerated. And while they were doing their time, they wanted their kids safe. They wanted help and they found their way to our school. One particular person applied, Clyde Screaming Eagle Salazar. Basically, he was the last man off of Alcatraz. He was slinging heroin. Where did he learn heroin? He was in the armed service. He said this feels good, but he also made a business of it and ended up in Alcatraz.

The reason I say this is that you never know who your teacher is going to be. They’re not who you think they’re going to be or look like, or even have the history you would think of. Castro couldn’t win his Cuban war, because he couldn’t blow up bridges. Clyde knew plastic explosives from being in the service. So he went to Cuba and blew up bridges, and within months Castro won.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

Would you say more about Screaming Eagle? He was an important figure for you, right?

JOHN MALLOY

Yes, and he ended up dead between two garbage cans with a needle in his arm. So he had good days and bad days.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

How did he help you?

JOHN MALLOY

One, he brought Native Consciousness to our school. He is the one who invited me to go on my first California Native American Indian five-hundred-mile spiritual marathon run, and now I’m the director of the run.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

So this was roughly what year?

JOHN MALLOY

It was 1978. Through that I met and walked with [labor organizer] Cesar Chavez.

He cooked the runners’ pancakes. So Clyde had a disease, but he brought me to Dennis Banks and the American Indian Movement.

Our team runs under the American Indian Movement’s flag. We have the authority to do the things we do. The run would end if we lost that connection or that trust.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

Screaming Eagle, in the way I’m hearing it, was your entry into the Native American community, and this has been an important thing for you.

JOHN MALLOY

Yes, along with Buddhism. I can’t make a bad decision because I have those on either side of me. I can’t go crooked because I have this belief system that makes it so easy to do the right thing. The right thing is to be inclusive. The right thing is to be of service. The right thing isn’t to have a bunch of things. There has to be a balance.

So I know how to say “no,” and I know how to say “yes.” I walk my talk so my mouth has got to match my feet. Because if my word wasn’t good, I wouldn’t be invited to ceremonies, to Sun Dances, Ghost Dances, Bear Dances, the sweat lodges, and more. I was invited in early and remember, this was in the time of COINTELPRO, where the FBI was spying on grassroots movements and plotting to instigate infighting and dissension in the American Indian Movement, the Black Panthers, the Young Lords.

I was in the middle of that. I know how the American Indian Movement became a spiritual movement, not just a political movement, not just an economic movement.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

What are some of the things you got from your involvement with Native Americans that have helped you?

JOHN MALLOY

.jpg) Well, number one, the earth ethic. Indigenous people believe that all life is sacred. That’s what we run for. It sounds like a simple statement: All life is sacred. Well, when you start realizing that the sky is sacred, the earth is sacred, the water is sacred—all these things are sacred—you don’t get pushed around. Let’s say we’re at Mt. Tamalpais and we have seventy runners. We’re going to run through a national park. We’re going to run through land where the water district is. We’re in the middle of the ceremony and all of sudden rangers show up. They start citing us, and people start with, “What are we going to do?” We’re going to surround those rangers in a good way so they can’t get back to their car. And we’re going to keep drumming and drumming. We’re going to let them know this is a prayer. No one tells us how we pray, or where we go.

Well, number one, the earth ethic. Indigenous people believe that all life is sacred. That’s what we run for. It sounds like a simple statement: All life is sacred. Well, when you start realizing that the sky is sacred, the earth is sacred, the water is sacred—all these things are sacred—you don’t get pushed around. Let’s say we’re at Mt. Tamalpais and we have seventy runners. We’re going to run through a national park. We’re going to run through land where the water district is. We’re in the middle of the ceremony and all of sudden rangers show up. They start citing us, and people start with, “What are we going to do?” We’re going to surround those rangers in a good way so they can’t get back to their car. And we’re going to keep drumming and drumming. We’re going to let them know this is a prayer. No one tells us how we pray, or where we go.

So then seventy runners take off and they call it into the next district. We runners disappear into the forest. The next thing we see is rangers from the national park. I say, “I see you’re training that horse. Can I bless it?” Then all of a sudden we become friends.

I use the earth ethic all the time with kids who feel suicidal or homicidal. It’s like when you commit an act of violence: you are basically disconnecting yourself. You are putting yourself outside the circle. You are connected to the circle. The circle includes the plants, the trees, and all life forms. You need to know the names of these trees. You need to be able to talk to that animal that’s hurt, that’s never going to fly again because it was shot out of the sky by someone who doesn’t know any better.

The Native Americans have taught me that everything is connected. Those sage bushes out in the desert, why are their leaves smaller? Why do their roots go down so far? Why is that? Because they’ve got to communicate to the next plant. They might say, “I’ve got more than I need. You can have this.” You start seeing how sophisticated and universal these truths are.

[Anthropologist] Angeles Arrien came into my life and gave me a list of truths. She formalized what I knew, and I was so grateful. Basically her research was all about indigenous First Peoples’ knowledge. And that’s what I wanted, because I saw urban, wounded people coming, and psychiatry didn’t work. The medical model didn’t work. Science didn’t work. Behavioral practices didn’t work.

What worked was the indigenous way where you see the god in everything. You revere everything. You learn the wind is sending you a message. You start honoring the invisible world. You start having a wow! in your life. The Native way is so freeing.

When Clyde Screaming Eagle Salazar introduced me to the California American Indian spiritual marathon relay, that’s when I began to meet the leadership of the American Indian Movement. I was a runner. I didn’t realize that in the Native American way, if you say yes to a commitment, that means four years—one year for each direction. This was early on in the Foundry School and I had a lot of responsibility. I expected the run to be finished in time. But there was a delay. We started four days later than I thought. That’s a good example of “Indian time.” We wait until we know it’s the right time.

This run was starting from DQ University and was going from Davis to Los Angeles.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

DQ University?

JOHN MALLOY

Yes. It’s by Davis, California. It’s the first Indian university west of the Mississippi. Dennis Banks became president. He was on that same run. My spiritual teacher today, Fred Short, was his bodyguard for eleven years. Dennis Banks had 250 years hanging over his head for doing the right thing. So Governor Brown said, “As long as you stay in California, you’re safe.” He gave him a pass. Dennis became the director at DQ University. He was hurting because back in ’77, ’78, Native people decided to walk all nations under one flag. They said, “We’re going to walk to Washington, D.C. from San Francisco, from Alcatraz, and get the freedom of religion act passed.” Before that, people were going to prison for what we take for granted today; for the sweat lodges, the sun dance, all that. You went to federal prison.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

You mean those things were illegal?

JOHN MALLOY

Yes, they were illegal. So we had a reason to run. We’ve always had a reason to run.

In 1977 in North America, the grandmas and the Warriors Society, the medicine people gathered. They called in people like Dennis Banks, young warriors. They talked and then said, “Your responsibility is to go to each village and tell them what we’re going to pass on to you.” What they passed on is, “Don’t get involved in politics and economics. Learn your language. Learn your dances. Learn your stories. Learn your songs. That’s the only thing that’s going to protect the sky and the earth.”

We went down to Cesar Chavez’s compound in La Paz and Tehachapi. They shook hands. Dennis said, “We’ll start to run here to honor your work for the United Farm Workers. This will always be the place we start.” Those agreements were met and kept; for twenty-five years that’s where we’ve started our route.

We’ve got Indians and Rainbow people who couldn’t run a lick who now run thirty miles a day for eighty-eight days with every fifth day off—2,800 miles from one ocean to the next. How do you explain it? How do you explain it when people say, “Well, the Indians used to run from Death Valley to the ocean”? How do we know that? Because of vision. We have five runners now who can run one-hundred miles in twenty-four hours. We trained them to do that. How did we know that was possible? Because of faith.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

Is the point of it, “Oh, you ran one-hundred miles in twenty-four hours?”

JOHN MALLOY

No.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

So talk about the real point of this long run.

JOHN MALLOY

It’s about bringing credibility. People think it’s so simple. It’s not simple to run one hundred miles. You’ve got to know a lot of things. Science can’t explain a lot of these things. They can’t explain spirit. We’re spiritual runners. We’re not competitive runners. You know, I had a vision that every kid that would go to the Foundry School had to run six miles within the first four days in our group. People might say, “Well, he’s got a bad leg, he’s got asthma.” There were people saying it was child abuse. There were administrators saying, “You’re going to kill somebody. You can’t do it.”

We did it anyway, because it was the right thing to do. It was the honest thing to do. Some of the kids who are forty today and have their own families say, “It was the greatest thing, John. I thought you were crazy, but we did it.” Now how did we do it? Group running.

Americans train individually. They keep secrets. Indigenous runners do everything together. How do the Tarahumara do it? We have a relationship with Tarahumara runners. We have relationships with all kinds of people. Once the trust is there, you start learning. You can’t be spiritual without going through the body. You can’t go to heaven until you’ve done your earth walk.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

That’s really something. You had this vision that every new kid would have to run six miles within four days? Did they all manage to do this?

JOHN MALLOY

Yes. And how did they do it? Because other kids wouldn’t let them quit. Then if a new kid came and said, “John, I can’t run,” the kid who didn’t think he could make it a month ago would say, “Can I go with you?”

The point is we imprison ourselves. I know people in prison more free than people walking around here. So we disable ourselves. If you’re comparing yourself like, “I can’t read like him,” or “I can’t run like him,” or “I can’t paint like that,” you’re basically putting coats over your power—which is a Native way of saying, “missing your medicine.” You have a responsibility to discover your medicine. And once you discover it, now your responsibility is to share it. That’s what this school did.

So you become a servant for the rest of your life. You don’t have a choice.

These kids also had to talk in front of a couple hundred people within weeks.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

Wow.

JOHN MALLOY

What did they have to talk about? Their story—not as a war story but as a medicine story. My story is connected to your story. So basically our students have outgrown us. That’s the way it should be.

So we go up to Pit River and train people for a whole year to run.

I’ll look at them. It’s 110 degrees out; your shoes are melted. The kid doesn’t have a shirt. I say, “Are you suggesting he’s earned anything?” I say, “You know his father would be angry at me for giving him a shirt. He hasn’t done anything yet.”

They don’t get it, but it’s principle before personality. Everything matters. The way you tie your shoes is the way you tie your black belt. Everything matters.

That’s still going on today. That’s my life. So the schools are one thing. That’s just humming.

I love teaching English. Kids who hadn’t been in school for years are in our school. They’ve got two years of “F”s. How can they become great writers? We introduce them to language. Mostly Mexicans are in the units that I worked. The administration won’t allow them to speak Spanish. So right away what happens? These kids start to hate English.

So how do you get them to come back? I say, “Do you know what my job is? My job is to get you to fall in love with language. That’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to teach you to write with your nose, your ears, your eyes, your hands, your tongue.”

RICHARD WHITTAKER

What do you mean?

JOHN MALLOY

They’re going to learn all the senses. They’re going to learn the miracle of the eye, the miracle of hearing. They’re going to learn it from physiology all the way to metaphor. “So why don’t you see any poems about oil? Why are all the poems about water? You want to be a lover? You want to be loved? You’ve got too much oil in you to be loved. You’re not loveable. You need to bring water in, clean water. So you need to bring up your language. Don’t ever swear in front of me again”—that kind of stuff. That is non-stop.

Then that kid is the one who gets up there and gives the greatest .JPG)

Now he teaches Mexican-American studies. There are so many thousands of stories—like on our run, at night we’ll sit around a big fire, and I ask them, “What’s your connection with the fire? What’s your connection with this group?”

They’ll start telling it. They’ll say, “I’ve got eighteen years clean.” Or, “I was molested and I was in the dark for so long and when I came to this group, all of a sudden, I realized what that shame and guilt was about. I broke the silence and all of a sudden ten other women walked up to me and said thank you.” This is non-stop.

RICHARD WHITTAKER

This is really something.

JOHN MALLOY

With Native people, it’s that way, man. It’s in the moment. You know the circles represent the four directions. So when we form a circle, people are trained that the first person stands in the east, the next the west and south and north. What that says is that it’s a human race. There is no exclusion. Everyone is welcome. It doesn’t matter what religion.

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of Works & Conversations, an inspiring collection of in-depth interviews with artists from all walks of life, and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

11 Past Reflections

On Jan 3, 2025 Sandhya Prakash wrote:

On Jan 2, 2025 Nathalie Sorrell wrote:

1 reply: Mia | Post Your Reply

On Jan 2, 2025 maria wrote:

On Jan 2, 2025 James wrote:

On Jan 2, 2025 Lulu wrote:

On Jan 2, 2025 Jude Cassel Williams wrote:

On Jan 2, 2025 Rochelle wrote:

On Jan 2, 2025 Pat Denino wrote:

1 reply: Steven | Post Your Reply

On Aug 16, 2016 Claire Fitiausi wrote:

"My story is connected to your story." Ad infinitum.

On Jan 3, 2025 Bruce wrote:

Post Your Reply